The Secret Lives of Medieval Books

A new method reveals which pages of ancient religious texts were most frequently used—and which prayers perpetually put readers to sleep

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120426025044book-small.jpg)

When medieval Europeans read religious texts, what were their favorite prayers? Which sections did they return to time and time again, and which parts perpetually put them to sleep?

These questions have long seemed unanswerable, but a new method by Kathryn Rudy of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland takes them on with an unexpected approach: examining the dirt on a book’s pages.

![]()

The most heavily worn payer in the manuscript was dedicated to St. Sebastian, who was thought to be efficacious against the bubonic plague. Image courtesy of the University of St. Andrews

Rudy hit on the technique when she realized that the amount of dirt on each page was an indication of how frequently the pages were touched by human hands. Dirtier pages were probably used most frequently, while relatively clean pages were turned to much less often. She determined the amount of dirt on each page and compared the values to reveal what passages were most appealing to medieval readers—and thus, what sorts of things they cared about while reading religious texts.

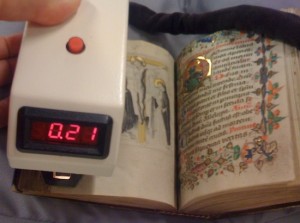

The densitometer used to analyze the amount of dirt on each page. Image courtesy of the University of St. Andrews

In a press release, Rudy said:

Although it is often difficult to study the habits, private rituals and emotional states of people, this new technique can let us into the minds of people from the past… were treasured, read several times a day at key prayer times, and through analysing how dirty the pages are we can identify the priorities and beliefs of their owners.

To gather the data, she put a densitometer to work. The device aims a light source at a piece of paper and measures the amount of light that bounces back into a photoelectric cell. This quantifies the darkness of the paper, which indicates the amount of dirt on the page.

Rudy then compared each of the pages in the religious texts tested. Her results are simultaneously predictable and fascinating: They show us that the worries of medieval people were really not so different from ours today.

At a time when infectious diseases could ravage entire communities, readers were deeply concerned with their own health—the most heavily worn prayer in one of the manuscripts analyzed was dedicated to St. Sebastian, who was thought to protect against the bubonic plague because his arrow wounds resembled the buboes suffered by the plague’s victims. Prayers for personal salvation, such as one that could earn a devoted individual a 20,000-year reduction of time in purgatory, were much more heavily used than prayers for the salvation of others.

Perhaps most intriguingly, Rudy’s analysis even pinpointed a prayer that seems to have put people to sleep. A particular prayer said early in the morning hours is worn and dirty for only the first few pages, likely indicating that readers repeatedly opened it and started praying, but rarely made it through the whole thing.

The research is fascinating for the way it applies an already developed technology to a novel use, revealing new details that were assumed to be lost to history. Most promisingly, it hints at the many untapped applications of devices such as a densitometer that we haven’t even imagined yet. What historical texts would you want to analyze? Or what other artifacts do you think still have something new to tell us if we look a little closer?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)