The Strange Beauty of David Maisel’s Aerial Photographs

A new book shows how the photographer creates startling images of open-pit mines, evaporation ponds and other sites of environmental degradation

![]()

For almost 30 years, David Maisel has been photographing areas of environmental degradation. He hires a local pilot to take him up in a four-seater Cessna, a type of plane he likens to an old Volkswagen beetle with wings, and then, anywhere from 500 to 11,000 feet in altitude, he cues the pilot to bank the plane. With a window propped open, Maisel snaps photographs of the clear-cut forests, strip mines or evaporation ponds below.

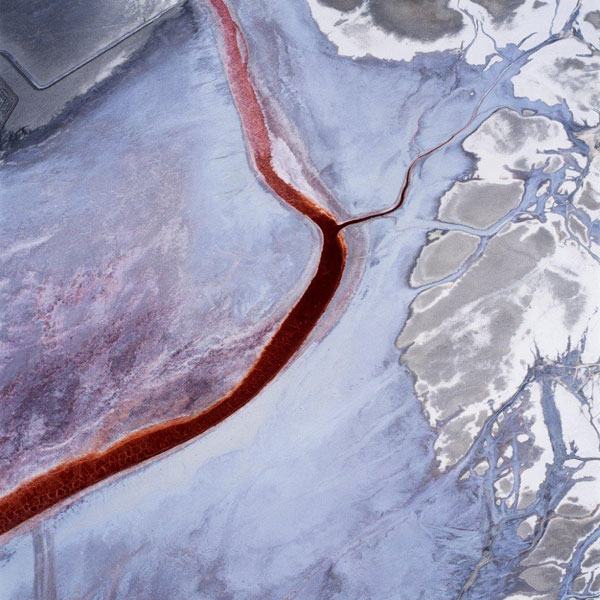

The resulting images are beautiful and, at the same, absolutely unnerving. What exactly are those blood-red stains? As a nod to the confusing state they place viewers in, Maisel calls his photographs black maps, borrowing from a poem of the same title by contemporary American poet Mark Strand. “Nothing will tell you / where you are,” writes Strand. “Each moment is a place / you’ve never been.”

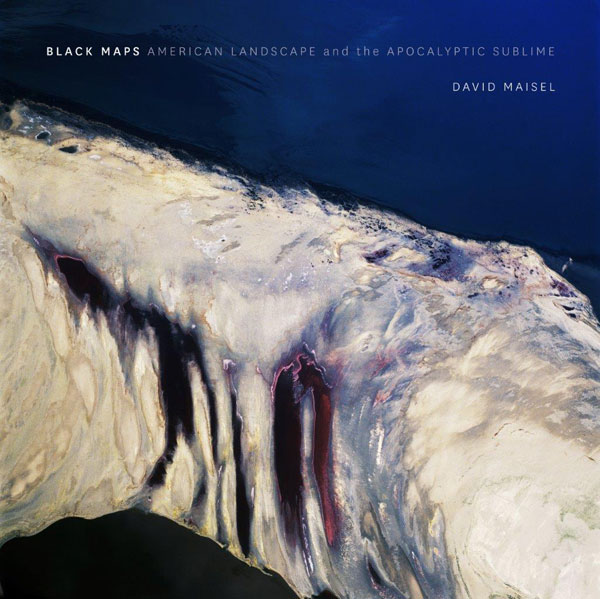

Maisel’s latest book, Black Maps: American Landscape and the Apocalyptic Sublime, is a retrospective of his career. It features more than 100 photographs from seven aerial projects he has worked on since 1985. Maisel began with what Julian Cox, the founding curator of photography at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, calls in the book an “extensive investigation” of Bingham Canyon outside of Salt Lake City, Utah. His photographs capture the dramatic layers, gouges and textures of the open-pit mine, which holds the distinction of being the largest in the world.

This series expanded to include other mining sites in Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada and Montana, until eventually Maisel made the leap from black and white to color photography, capturing the bright chemical hues of cyanide-leaching fields in The Mining Project (a selection shown above). He also turned his lens to log flows in Maine’s rivers and lakes in a project called The Forest and the dried bed of California’s Owens Lake, drained to supply Los Angeles with water, in The Lake Project.

Oblivion, as the photographer describes on his personal Web site, was a “coda” to The Lake Project; for this series of black and white photographs, reversed like x-rays, Maisel made the tight network of streets and highways in Los Angeles his subject—see an example below. Then, in one of his most recent aerial endeavors, titled Terminal Mirage (top), he photographed the Mondrian-like evaporation ponds around Utah’s Great Salt Lake.

All combined, Maisel’s body of work is what Cox calls “a medley of terrains transformed by humankind to serve its needs and desires.” The narrative thread, he adds in the introduction to Black Maps, is the photographer’s aim to convey humans’ “uneasy and conflicted relationship with nature.”

I wrote about Maisel’s photography for Smithsonian in 2008, when his “Black Maps” exhibition was touring the country, and at that time, the Long Island, New York-native hedged from being called an “environmental activist.” As Cox astutely notes, “The photographs do not tell a happy story,” and yet they also “do not assign any blame.” Maisel is attracted to these landscapes because of their brilliant colors, eye-catching compositions and the way they emote both beauty and danger.

Maisel’s photographs are disorienting; it is a mental exercise just trying to orient oneself within the frame. Without providing solid ground for viewers to stand on, the images inevitably spark more questions than they do answers.

Each one is like a Rorschach test, in that the subject is, to some extent, what viewers make it to be. Blood vessels. Polished marble. Stained-glass windows. What is it that you see?

An exhibition of Maisel’s large-scale photographs, Black Maps: American Landscape and the Apocalyptic Sublime, is on view at the CU Art Museum, University of Colorado Boulder, through May 11, 2013. From there, the show will travel to the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art in Scottsdale, Arizona, where it will be on display from June 1 to September 1, 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)