The Tattoo Eraser

A new type of body art ink promises freedom from forever

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/tattoo_remove_beads_388.jpg)

Like jumbo shrimp or freezer burn, tattoo removal is a somewhat contradictory concept. From a purist's standpoint, a tattoo's permanence reflects the eternity of its subject: a guiding philosophy, the memory of a departed, one's love for mom. More practically, body art is plain hard to remove; throughout thousands of years of tattoo tradition, the perfect eraser has remained elusive.

Until now. A company called Freedom-2, formed by a group of scientists, aims to re-write that history, and to wipe out any unwanted tattoos along the way. The researchers have created body art that can be removed in full with a single laser treatment.

"The main problem we have with removing tattoos is you can't predict what the outcome's going to be," says Dr. Rox Anderson, a dermatologist at Harvard Medical School who co-founded Freedom-2. "We're removing that gamble."

Ancient forms of tattoo removal included primitive dermabrasion—scraping the skin with rough surfaces, such as sandpaper. Romans used such a method as early as the first century, when soldiers returned from exotic regions with taboo markings.

Modern laser tattoo removal is credited to University of Cincinnati dermatologist Leon Goldman, who unveiled his method in the late 1960s. Goldman's laser assaulted the tattooed skin with "hot vapor bursts" that left it charred, Time magazine described on Oct. 20, 1967. Even at its best, the process left behind "cosmetically acceptable scars."

In the late 1980s, Anderson improved Goldman's procedure, creating a laser system that removed a tattoo, scar and all. But even Anderson's method worked only three-quarters of the time, he says. The process is also unpredictable, requiring as many as 20 monthly treatments that can cost thousands of dollars a pop.

Enter Freedom-2, formed in 2004 by Anderson, Bruce Klitzman of Duke University, a few other colleagues and some business partners. The group takes a new approach to the removable tattoo conundrum. Instead of focusing on laser improvement, they have created an ink that dissolves naturally in the body when treated just once with a typical removal laser.

"I realized it's better to work on the ink than on the laser," Anderson says. "This is the first time a tattoo ink has actually been designed from a biological and material science point of view."

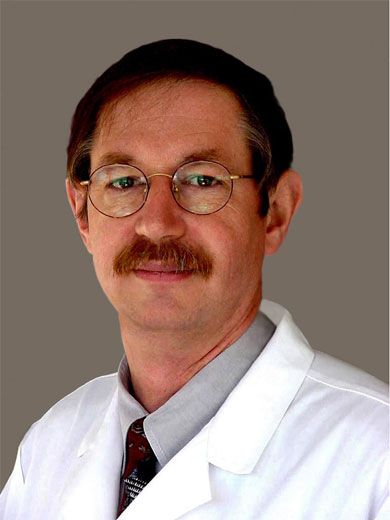

Typical tattoo inks are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. While some are made safely from carbon or iron oxide, others, particularly yellow compounds, contain carcinogens. The ink rests in tiny beads that remain lodged in the skin after a tattoo is applied. During removal, a laser blasts these nano-sized beads with enough heat to make them rupture, releasing the ink into the body. Some of the potentially harmful ink ends up in the body's lymph nodes, part of the immune system.

Freedom-2 inks are made from safe pigments—the orange ink, for example, contains beta-carotene, commonly found in carrots—and trapped in harmless polymer shells. When a Freedom-2 tattoo is removed by laser, the ink dissolves biologically, leaving only the innocuous, invisible shells.

"We're helping to change and make safe once again the art form of tattooing," says Martin Schmieg, the company's chief executive.

Freedom-2 inks could hit the market as early as mid-2007, offering a hedge to the growing population of people with a tattoo. A study in the September 2006 Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology showed that about one quarter of adults age 18 to 50 in the United States currently have a tattoo. Of those, almost 30 percent had considered removing or covering the tattoo with a new one, or had already covered it.

The new ink will also entice anyone too apprehensive to get inked in the first place, Schmieg predicts.

"The number one reason people don't get a tattoo is permanence," he says. "When you remove that issue, we believe there will be a natural growth in the number of people getting tattoos."

The scientists are also designing polymer shells that biodegrade on their own, without a laser's nudge, over a matter of months, says Edith Mathiowitz of Brown University, who engineered Freedom-2's beads.

"This could be a new type of jewelry," Mathiowitz says.

If Freedom-2 succeeds, it will dispel yet another contradiction: the scientifically researched tattoo. The new ink has been tested on laboratory animals and will soon undergo human clinical trials—an unprecedented amount of rigor for the tattoo industry, says Anderson.

"This is about greatly reducing the risk of getting a tattoo," he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)