The Ten Most Spectacular Geologic Sites

Smithsonian picks the top natural wonders in the continental United States

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Meteor-Crater-Arizona-631.jpg)

Certain travel destinations remind you that you live on a planet—an old, weathered, tectonic-plate-shifting planet. The Earth has been smothered by glaciers, eroded by wind and water, splattered with lava and slammed by debris from outer space. Yet these geologic forces have left behind some of the most fascinating must-see sites in the continental United States.

10. Lava Beds National Monument, California

Volcanic rock is vicious stuff: black, jagged, crumbly and boot-shredding. But if you look at it right, you can sense the power of the volcano that spewed it out. The Medicine Lake volcano at the northern border of California has been erupting for half a million years. (Its last gasp was 900 years ago; the next one? Who knows.) The volcano has produced some awesome classic geologic features that are easily accessible at Lava Beds National Monument.

You can see tuff (compacted ash), long flows of pahoehoe (ropy, rounded lava) and aa (the pointy rock named for the exclamations one makes when trying to walk across it). Cinder cones surround vents where lava erupted in short, gassy blasts; spatter cones were formed by thicker, heavier lava.

But the highlight of the national monument is the lava tubes. When lava flows in channels, the exterior can cool and solidify while the interior is still hot and molten. If the lava inside flushes through, it leaves behind a warren of surreal caves that are just the right size for spelunking. The park has the longest lava tubes in the continental United States; bring a flashlight to explore them. Some are deep and dark enough that they have ice year-round.

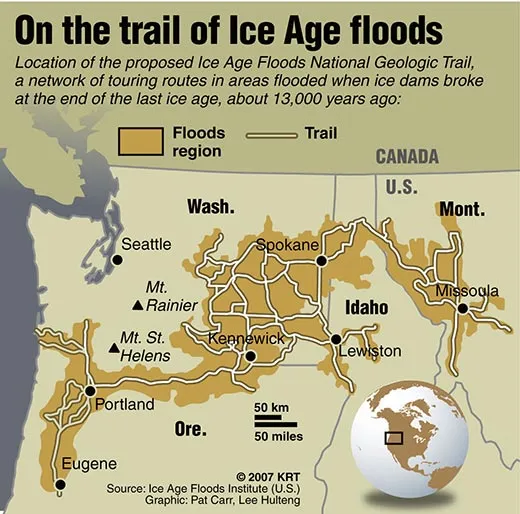

9. The Ice Age Flood Trail, Washington, Oregon and Idaho

During the last ice age, about 18,000 to 12,000 years ago, an immense lake covered the western edge of Montana. The lake water was trapped by a glacier along the Idaho panhandle that acted as a dam. When the dam melted, the entire lake—as much water as in Lake Ontario and Lake Erie combined—surged across Idaho, Oregon and Washington to the sea. It drained in about two days.

This epic flush may sound like the flash flood of all flash floods. But the whole process happened repeatedly during the last ice age and during previous ice ages as well.

These massive floods gouged out basins all along the Columbia River, deposited 200-ton boulders throughout the area and scoured the territory now known as the Scablands.

A bill to create an Ice Age National Geologic Trail (more of a driving route than a hiking trail) passed Congress this year and would establish information centers at some of the more dramatic flood sites.

8. Mammoth Cave National Park, Kentucky

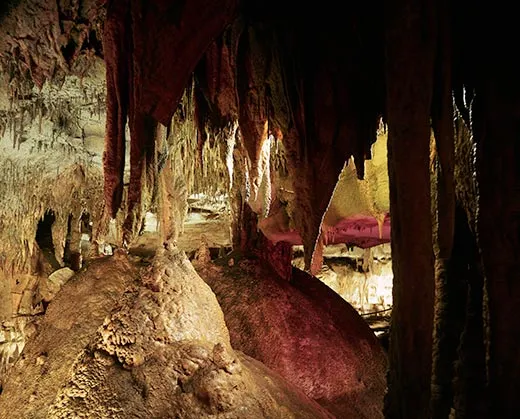

It's the longest cave in the world. No other known cave comes close. About 360 miles have been surveyed so far, and geologists estimate that the cave system’s total length is about 1,000 miles.

The cave runs through 350-million-year-old limestone, composed partly of shells deposited when Kentucky was at the bottom of a shallow sea. A wide river later replaced the sea and left a layer of sandy sediment on top of the limestone. Water dissolves limestone more readily than sandstone, so over millions of years rivers and rainwater have seeped through and eroded the limestone, creating caves. You can see all the classic cave features here: stalactites, stalagmites, crystals of gypsum, blind fish, narrow passages and “bottomless pits,” which park rangers point out to scare children.

7. San Andreas Fault at the Carrizo Plain, California

For a fault that regularly topples buildings, rips apart bridges and kills people, the San Andreas can be surprisingly hard to see. The best place to observe the 800-mile-long fault is along the Carrizo Plain, west of Los Angeles. The land is undeveloped, dry and fairly barren, so the trenches formed by past earthquakes haven’t been worn away by erosion and plants don’t obscure the view.

The San Andreas is the grinding, lurching plane of contact between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate. The Pacific Plate is pushing south-southeast and the North American is pushing north-northwest, rubbing uncomfortably against each other as they travel in opposite directions.

6. La Brea Tar Pits, California

In downtown Los Angeles, just off Wilshire Boulevard, is an unprepossessing geologic feature: a pit of oozing oil. The sticky asphalt has been trapping animals—including the occasional hapless pigeon—and preserving their skeletons for at least 40,000 years.

The museum at the tar pits displays wall after wall of dire wolves, saber-toothed cats, Columbian mammoths, ground sloths and camels. The skeletons are plentiful and beautifully preserved (the animals sank pretty quickly in their death throes). It's the best place to get a sense of the animals that roamed North America before humans arrived.

5. Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, Washington

The visitor center near the top of Mount St. Helens is named for David Johnston, the geologist who predicted that the volcano would explode not upward but sideways. He was six miles away when the volcano erupted on May 18, 1980. Johnston saw the eruption, radioed it in and was killed by the pyroclastic blast of gas and rock.

Mount St. Helens, like most of the peaks in the Cascade Range, is part of a “ring of fire“ around the edge of the Pacific Ocean. The oceanic plates are burrowing under continental plates and causing earthquakes and volcanoes, even about 100 miles inland from the coast. From the Johnston Observatory, you can see a line of volcanoes—all quiet for now—stretching to the north and south.

The eruption was the first in the continental United States since Mount Lassen, in Northern California, erupted in 1915 (also well worth a visit). The Mount St. Helens eruption killed 57 people, destroyed 230 square miles of forest and rained ash as far east as Wisconsin.

Almost 30 years later, you can still see the dead zone as you approach the mountaintop: toppled trees, charred stumps, ash and mud flows. But the zone is coming back to life, and now the mountain is the site of an important ecological study of how species return to land that has been sterilized.

4. Meteor Crater, Arizona

If it weren't for Earth's water, our planet would look a lot like the moon—pockmarked and blasted by impacts from comets, asteroids and meteorites. Our thick atmosphere burns up most space detritus before it hits Earth's surface, but some big chunks still get through. Most impact sites are impossible to see because they're covered by water or vegetation. (There's a big impact crater half-submerged in the Chesapeake Bay, and of course the remnants of the dinosaur-killing asteroid off the Yucatán Peninsula.)

The best place to see the remnants of an impact is Meteor Crater, east of Flagstaff, a privately owned tourist attraction. The crater is 4,000 feet wide, almost 600 feet deep and will put the fear of Near Earth Objects into you.

3. Niagara Falls, New York

The border town is great kitschy fun, but it's also fascinating geologically. The falls may not be the highest in the world, but their width and the volume of water spilling over them (about six million cubic feet per second) make them stunning (and deafening).

Niagara Falls is where one great lake (Erie) drains into another (Ontario). The lakes were carved by glaciers at the end of the last ice age. A hard capstone (the top of the falls) eroded more slowly than the soft shale below, creating the falls.

The falls do hold one world record: they may be the fastest moving in the world geologically. The water is constantly eating away at the lower layer of rock, including material directly underneath the capstone. When enough of the supporting layer wears away, the upper layer collapses, dropping boulders at the base of the falls and moving the tip of the falls upstream. The waterfall has moved seven miles in the past 12,500 years.

2. Yellowstone National Park, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming

The nation’s first national park is basically the top of a still-sort-of-active volcano. Classic volcanoes are topped by a caldera, a caved-in area from which lava has erupted. Yellowstone also has a caldera, only it is hard to recognize because it is 45 miles across.

Yellowstone is the latest bit of North American crust to sit atop a stationary hotspot in the Earth’s mantle. A chain of volcanic rock from past eruptions marks where the continent has swept across the hotspot.

The last true eruption at Yellowstone was about 70,000 years ago, but the park still has plenty of seismic hydrothermal activity.

The hotspot fuels the crazy fumaroles (steam vents), hot springs, mud pots (hot springs with a lot of clay) and geysers. Old Faithful geyser gets most of the attention, but the park has 300 of them—the most anywhere on Earth.

1. Grand Canyon, Arizona

Ahh, the Grand Canyon. It's stunningly beautiful, a national treasure and perhaps the one place that will make you feel utterly insignificant in both space and time.

Our planet is about 4.6 billion years old. You can descend through almost half of that history by hiking to the bottom of the mile-deep canyon. The youngest layers at the top were deposited pretty much yesterday, geologically speaking, and the oldest, deepest layers of sedimentary rock about 2 billion years ago. Take a chart of the layers with you when you visit; even if you decide to view the canyon from above, it is the best place on Earth to try to comprehend the vastness of geologic time.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article mistakenly placed Mt. St. Helens in Oregon instead of Washington State. We regret the error.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)