The World’s Fastest Animal Takes New York

The peregrine falcon, whose salvation began 40 years ago, commands the skies above the Empire State Building

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Peregrine-Falcon-New-York-City-631.jpg)

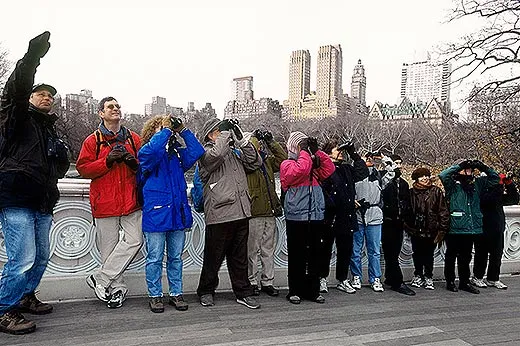

I’m standing a thousand feet above the streets of New York City, on the 86th floor observatory deck of the Empire State Building, looking for birds. It’s a few hours after sunset, and New York City naturalist Robert “Birding Bob” DeCandido is leading our small group. We can see the cityscape in every direction as the cool wind tousles our hair, but our gaze is focused up. Migrating songbirds, many of which travel by night to keep cool and avoid predators, are passing high overhead on their autumn journey. DeCandido has taught us how to differentiate the movement of small birds—“See how they flap-flap-glide?” he tells us—from the erratic motions of moths, But there is another denizen of the city’s skies that we’re all hoping to see.

A blur of a bird zips past the western flank of the building, level with the observatory. It’s too fast for a gull, too big for a songbird. Maybe a pigeon. Maybe something else. There is an excited buzz as we fumble with binoculars, unable to track the receding figure.

Ten minutes after that first flash, an unmistakable form draws our eyes directly overhead. Collectively, we cry, “Peregrine!” The falcon is smaller than the red-tailed hawks that live in Central Park, and sleeker, with a long, narrow tail that flares as the bird turns and sharp, pointed wings that propel its body fiercely. It loops around the building, in complete control as it navigates the blustery night air, its undersides transformed into a ghostly white by the upward shine of the building's glaring spotlights. It closes in on a potential perch midway up the spire and then suddenly veers south and disappears into the night.

“Come back,” someone whispers plaintively.

“Show me the top of the food chain,” says another.

*

There is a reason fighter jets and football teams are named after falcons. At their standard cruising speed of 40 miles per hour, peregrines are apace with pigeons and many other birds that are the basis for their diet, but falcons can go into overdrive in an aerial feat known as a stoop. They rise dozens of feet above their prey, tuck their wings in tightly against their bodies, and dive – a furious, feathered mission. The fastest animal on earth, they have been clocked at over 200 miles per hour as they descend upon their target, balling up their talons to stun their prey and then – supremely agile, able to turn upside down with a quick flip of the wing – scooping up their meal.

Forty years ago, we couldn’t have seen a peregrine falcon from atop the Empire State Building, or anywhere else on the entire East Coast. They were nearly obliterated in the middle of the 20th century by the effects of the pesticide DDT. Seed-eating songbirds fed on treated crops and were in turn eaten by the avian predators hovering at the top of the ecological pyramid. The pesticide didn’t kill adult falcons, but it concentrated in their tissues and interfered with females’ ability to produce strong eggshells. Brooding peregrines, settling down upon their clutches to keep them warm, were crushing their progeny with the weight of their bodies. In 1962, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published, warning of the unintended consequences of our new chemical age. By 1964, not a single peregrine falcon was found east of the Mississippi River.

In 1970, an improbable team of scientists and falconers that became known as the Peregrine Fund banded together at Cornell University in upstate New York to bring back the birds. Under the guidance of ornithologist Tom Cade, they planned to breed the birds in captivity and then release them into the wild after DDT had been banned, which it was in 1972. Because so few of the native falcons were left in the wild in the continental United States, they gathered peregrine falcons from around the globe, creating an avian immigrant story. They used the few members they could find of the subspecies that had dominated the United States, Falco peregrinus anatum, but added a handful of other birds—of the F. p. pealei subspecies from British Columbia and peregrinus from Scotland, brookei from Spain and cassini from Chile, tundrius from arctic Alaska and macropus from the southern reaches of Australia. While some people objected to the mixing of lineages, the scientists knew their options were limited. They also made the argument that hybridization could actually be a boon to a species that was facing a genetic bottleneck if they survived at all. “A peregrine is a peregrine,” Cade told me. Give the new generation of peregrines all the world’s genes, the logic went, and at least some of the birds will be fit to replace America’s lost peregrines—to traverse the fields of this region, live off the bounty of its airborne harvest, nest along its rocky cliffs.

The Peregrine Fund started with a small team of staff and volunteers who skirted building codes as they lived illegally in the peregrine breeding barn, cooking on a two-burner hot plate and bathing with a garden hose through upstate New York winters – anything to be with the birds 24/7 during the tenuous process of raising the vulnerable chicks. Using both natural and artificial insemination, breeding began in 1971, and just two years later, the Peregrine Fund newsletter announced a “bumper year.”

“In 1973, we raised 21 young from three fertile pairs,” Cade told me. “That clinched it in our minds that we could do this. We’d need dozens of falcons, but not hundreds.” With 30 breeding pairs, they could repopulate the eastern United States. Starting in 1974, the Fund began to release fledgling birds in prime peregrine habitat, wild places from New York's Adirondack Mountains to Maine's Acadia National Park.

Then the birds reappeared, against all expectation, in the largest city around. A peregrine released in New Hampshire in 1981 showed up on the Throgs Neck Bridge in New York City two years later, the beginning of the abundance we see today. Over the course of nearly two decades, more than 3,000 young peregrines were released across the United States. Thousands of pairs are now breeding in the wild in North America, and the birds were taken off the federal endangered species list in 1999, although they remain listed in New York State, where 160 birds were released. Something shifted upon their return. Their old cliffside nesting sites along the Hudson River Valley and elsewhere still existed, but many falcons chose the city instead. Immigrant birds had come to the city of immigrants.

From the observation platform, we continue to watch songbirds pass high above us as crowds of tourists maneuver slowly along the perimeter, taking photographs and pointing, speaking in French, Japanese, Italian and other tongues. Some pause by our group, eavesdropping, as DeCandido points to where peregrines have come to nest in the city—on the nearby MetLife building, the New York Hospital, the Riverside Church, the George Washington Bridge, the Brooklyn Bridge and the 55 Water Street building. They nest 693 feet up the distant Verrazano-Narrows Bridge that’s lit up in a twinkling string of green sparkles and have taken over an osprey nest in the darkness of Jamaica Bay.

At least 17 breeding pairs live within the borders of the five boroughs, the densest known population of urban peregrines in the world. The new generation adapted to the concrete canyons, towering bridge supports and steel skyscrapers of Gotham, redefining falcon habitat. It was as though we had built them a new world, with perfect nest sites—high, adjacent to wide expanses of open flyways for hunting and populated with an endless, year-round food source in the form of pigeons, another cliff-dwelling bird that finds our urban environment so pleasing. A biologist from the New York City Department of Environmental Protection makes annual rounds to the peregrine sites, banding young and building sheltering boxes wherever they have chosen to nest.

The Empire State Building granted peregrines the additional gift of a nighttime hunting perch, smack in the middle of one of North America's busiest bird migration routes. The building's lights were the brightest continuous source of artificial light in the world when they were installed in 1956. Today, the illumination makes it easy for peregrines to spot their migrating prey. It’s happening elsewhere. Peregrine falcons have been observed hunting at night in England and France, Berlin, Warsaw and Hong Kong, and off brightly lit oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. Many bird populations are plummeting because of habitat loss and other environmental threats, but peregrine falcons are thriving, brought back from the brink, returned, reintroduced and reimagined back into existence through science and passion.

*

DeCandido didn’t start coming to the Empire State Building in search of falcons, though. He came to count songbirds—dead ones. Generally, birds get the sky and we get the earth, but sometimes there’s a mix-up, and the two territories overlap. One morning in 1948, 750 lifeless birds were found at the base of the Empire State Building. “Mist Bewilders Migrators… Tiny Bodies Litter 5th Avenue,” announced The New York Times.

That was a record night, but every day, dead birds are found at the base of buildings. A recent study by New York City Audubon estimated that 80,000 birds perish each year in the five boroughs because of collisions with buildings. Ornithologist Daniel Klem of Muhlenberg College, who has studied bird collisions for more than 20 years, estimates that hundreds of millions of birds die each year from striking glass windows—more avian deaths than are caused by cats, cars and power lines combined. Compared with building strikes, peregrines and other avian predators barely make a dent in overall songbird populations.

DeCandido first went to the Empire State Building in the fall of 2004, prepared to witness migrants crashing into windows. Instead, over 77 nights, he and his team of volunteers found only four dead birds and discovered a miraculous New York nighttime bird-watching site. They checked off 10,000 birds on their clipboards that fall—Baltimore orioles and gray catbirds and black-throated blue warblers. Chimney swifts and common nighthawks. Great egrets and night herons. Gulls and geese. A saw-whet owl and a short-eared owl. And other flying creatures, such as little brown bats and red bats, snatching moths and dragonflies. On more than half of the nights, they were accompanied by a peregrine falcon, hunting by the bright lights of the big city.

DeCandido’s work confirmed what Klem, the Audubon researchers and others were finding—that most bird fatalities happen at the lower levels of structures, especially when glass reflects landscaping and creates the lethal illusion of a resting spot. Landscape architects are beginning to take placement of ornamental plants into consideration to minimize this deception while design firms continue to develop a type of glass that looks to a bird, in one architect’s words, “as solid as stone.”

*

Fifteen minutes after our first sighting, the falcon returns to lie in wait on the northern side of the spire, with a clear view of incoming bird traffic. A few minutes later, a small form approaches with the flap-flap-glide movement of a songbird. As it appears within our halo of light, the falcon charges from its station, circling wide and then closing in fast on the unsuspecting creature. The peregrine comes down hard on the bird, which drops straight down as though injured, but the falcon swerves off, talons empty, returning to another perch overhead. The smaller bird, DeCandido explains, folded its wings and dropped to escape.

The falcon has speed, but this alone doesn’t secure dinner. Persistence is a requirement as well. Every few minutes, the falcon launches itself after a weary migrant, but each time, the hunter misses its quarry. Then DeCandido declares a faraway, lit-up speck to be an approaching rose-breasted grosbeak. The small bird veers east as the peregrine rises, for the sixth time, both disappearing behind the spire. We lose sight of them on the far side, gauging their speed and waiting for them to emerge on the other side of the tower. They don’t. Just the falcon appears, landing briefly back on its perch. “Did he get it?” someone asks, necks straining, eyes glued to binoculars in a hard squint. And then the falcon lifts off, and we can see the limp bird held tightly in its grasp as it drops down to the northwest, toward the Riverside Church perhaps, wings arched, gliding down to some favorite plucking post to eat.

The peregrines have returned. To North America, and—unexpectedly—to many of the cityscapes of the world. When it comes to bird habitat, humans have destroyed more than we have created, but for the falcons we have inadvertently made a nice home. Songbirds pass overhead as the night goes on, but the small beings can no longer hold our attention. It’s not even 9 p.m., early for us city folk, so we return to the sidewalk realm of humans and down farther into the subway tunnels below, leaving the secret avian superhighway above to carry on its mysterious motions of life and death, the top of the food chain that has returned, reigning over all.