The World’s Rarest Whale Species Spotted in New Zealand

A pair of spade-toothed whales washed ashore on a beach, the first time the complete body of a member of this species has ever been seen

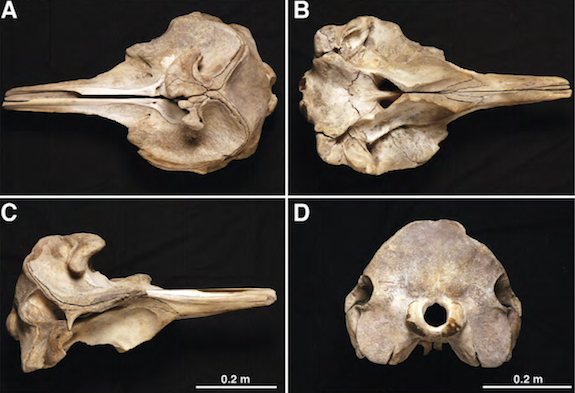

Scientists discovered a pair of spade-toothed carcasses in New Zealand. Previously, the species was only known from specimens such as this skull found in the 1950s, currently held at the University of Auckland. Image via Current Biology

In December 2010, visitors to Opape Beach, on New Zealand’s North Island, came across a pair of whales—a mother and her calf—that had washed ashore and died. The Department of Conservation was called in; they took photos, collected tissue samples and then buried the corpses at a site nearby. At first, it was assumed that the whales had been relatively common Gray’s beaked whales, widely distributed in the Southern Hemisphere.

Months later, when researchers analyzed the tissue DNA, they were shocked. These were spade-toothed whales, members of the world’s rarest whale species, previously known only from a handful of damaged skulls and jawbones that had washed ashore over the years. Until this find, no one had ever seen a complete spade-toothed whale body. The researchers scrambled to exhume the corpses and brought them to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa for further analysis.

“This is the first time this species—a whale over five meters in length—has ever been seen as a complete specimen, and we were lucky enough to find two of them,” said biologist Rochelle Constantine of the University of Auckland, one of the authors of a paper revealing the discovery that was published today in Current Biology. “Up until now, all we have known about the spade-toothed beaked whale was from three partial skulls collected from New Zealand and Chile over a 140-year period. It is remarkable that we know almost nothing about such a large mammal.”

The species belongs to the beaked whale family, which is relatively mysterious as a whole, mostly because these whales can dive to extreme depths and for very long periods—as deep as 1,899 meters and for as long as 30 minutes or more. Additionally, the majority of beaked whale populations are thinly distributed in very small numbers, so of the 21 species in the family, there are thorough descriptions of only three.

Of these species, the spade-toothed whale may have been the most mysterious. Scientifically known as Mesoplodon traversii, it was named after Henry H. Travers, a New Zealand naturalist who collected a partial jawbone that was found on Pitt Island in 1872. Since then, a damaged skull found on White Island in the 1950s and another found on Robinson Crusoe Island off the Coast of Chile in 1986 are the only evidence of the species.

Because the whales were never seen alive, scientists knew nothing of their behavior. In the paper, they are described as “the least known species of whale and one of the world’s rarest living mammals.”

“When these specimens came to our lab, we extracted the DNA as we usually do for samples like these, and we were very surprised to find that they were spade-toothed beaked whales,” Constantine said. To determine that, the researchers compared mitochondrial DNA from both of the stranded whales’ tissue samples and found that they matched that from the skulls and jawbones collected decades ago. “We ran the samples a few times to make sure before we told everyone,” Constantine said.

The researchers note that New Zealand’s national policy of collecting and sequencing DNA from all cetaceans washed ashore has proven especially valuable in cases like these—if this policy weren’t in place, no one might ever have known that the body of a spade-toothed whale had been seen for the first time.

This delayed discovery of a species that has been swimming the oceans all along hints at how much we still don’t know about the natural world—especially the oceans—even in this well-informed age. “It may be that they are simply an offshore species that lives and dies in the deep ocean waters and only rarely wash ashore,” Constantine said, explaining how it could take so long to find the species for the first time. “New Zealand is surrounded by massive oceans. There is a lot of marine life that remains unknown to us.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)