These Four Black Women Inventors Reimagined the Technology of the Home

By designating the realm of technology as ‘male,’ we overlook key inventions that took place in the domestic sphere

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/97/8f976919-d50e-46b0-a4c5-304abf759f2e/g37tw0_1.jpg)

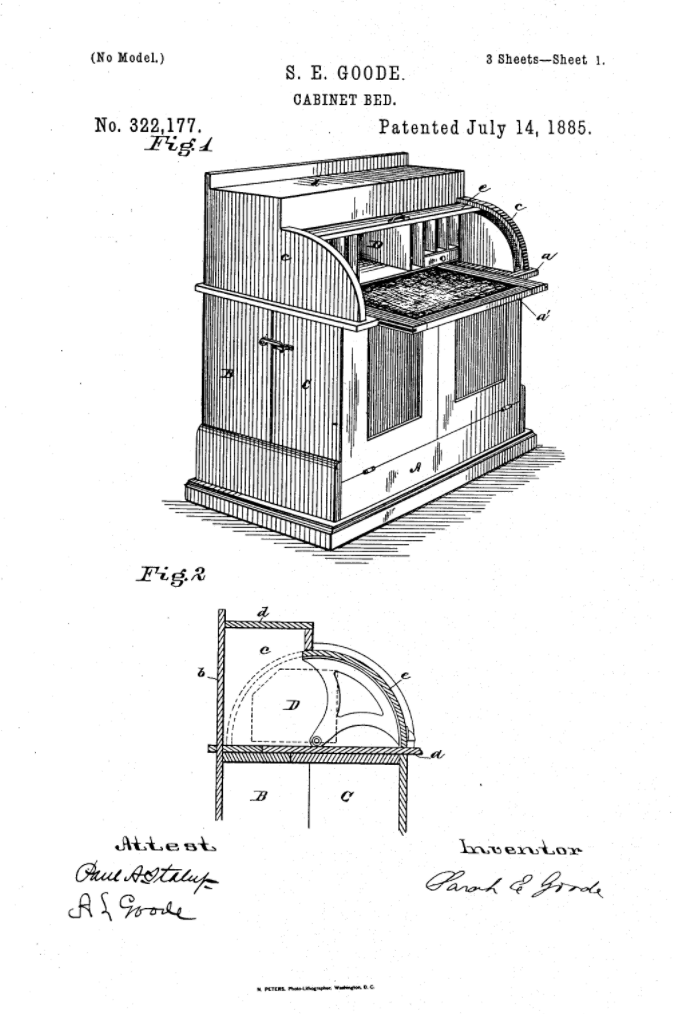

In 1888, a woman named Sarah Goode applied for and was granted a patent in Chicago, Illinois. Goode had just conceptualized what she called the "cabinet-bed," a bed designed to fold out into a writing desk. Meeting the increasing demands of urban living in small spaces, Goode invented the cabinet-bed “so as to occupy less space, and made generally to resemble some article of furniture when so folded.”

Goode was a 19th century inventor who reimagined the domestic space to make city living more efficient. Yet unless you’re a very specific kind of historian, you’ve probably never heard of her name. She doesn’t appear in history books, and what she did remains largely unknown. The same goes for Mariam E. Benjamin, Sarah Boone and Ellen Elgin—all 19th century African-American women who successfully gained patents in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds.

In a post-Civil War America, job opportunities and social mobility for African-American citizens were highly restricted. The obstacles for African-American women were even stronger. Universities seldom accepted women—let alone women of color—into their programs. And most careers in science and engineering, paid or unpaid, remained closed off to them for decades to come.

Women faced similar discrimination in the patent office, as law professor Deborah Merritt notes in her article “Hypatia in the Patent Office,” published in The American Journal of Legal History. “Restrictive state laws, poor educational systems, condescending cultural attitudes, and limited business opportunities combined to hamper the work of female inventors,” Merritt writes. And in the era of Reconstruction, “[r]acism and a strictly segregated society further encumbered female inventors of color.”

As a result, historians can identify only four African-American women who were granted patents for their inventions between 1865, the end of the Civil War, and the turn of the 19th century. Of these, Goode was the first.

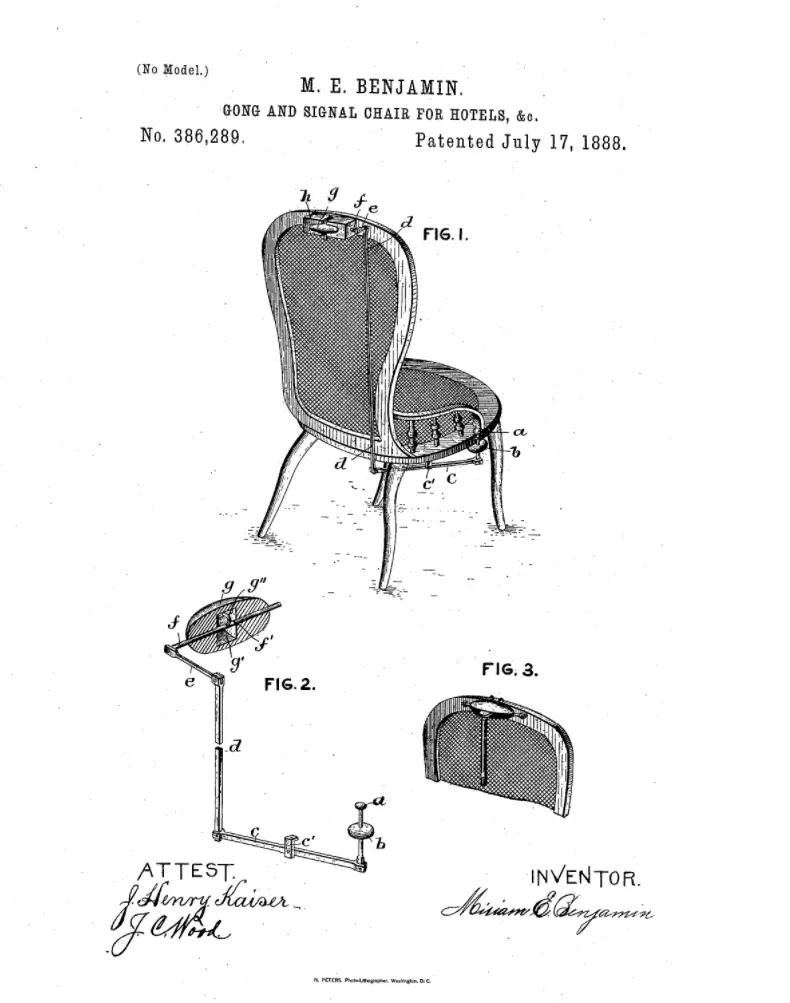

The second was schoolteacher named Mariam E. Benjamin. Benjamin was granted her patent by the District of Columbia in 1888 for something called the gong and signal chair. Benjamin’s chair allowed for its occupant to signal when service was needed through a crank that would simultaneously sound a gong and display a red signal (think of it as the precursor to the call button on your airplane seat, which signals for a flight attendant to assist you).

Benjamin had grand plans for her design, which she laid out in her patent paperwork. She wanted her chair to be used in “dining-rooms, in hotels, restaurants, steamboats, railroad-trains, theaters, the hall of the Congress of the United States, the halls of the legislatures of the various States, for the use of all deliberative bodies, and for the use of invalids in hospitals.” Intending to see her invention realized, Benjamin lobbied to have her chair adopted for use in the House of Representatives. Though a candidate, the House opted for another means to summon messengers to the floor.

Next was Sarah Boone, who received a U.S. government patent from the state of Connecticut for an improvement on the ironing board in 1892. Before her improvement, ironing boards were assembled by placing a board between two supports. Boone’s design, which consisted of hinged and curved ends, made it possible to iron the inside and outside seam of slim sleeves and the curved waist of women’s dresses.

In her patent paperwork, Boone writes: “My invention relates to an improvement in ironing-boards, the object being to produce a cheap, simple, convenient, and highly effective device, particularly adapted to be used in ironing the sleeves and bodies of ladies garments.”

Ellen Elgin might be completely unknown as an inventor if not for her testimony in an 1890 Washington, D.C. periodical The Woman Inventor, the first publication of its kind devoted entirely to women inventors. Elgin invented a clothes wringer in 1888, which had “great financial success” according to the writer. But Elgin did not personally reap the profits, because she sold the rights to an agent for $18.

When asked why, Elgin replied: “You know, I am black, and if it was known that a negro woman patented the invention, white ladies would not buy the wringer; I was afraid to be known because of my color in having it introduced to the market, that is the only reason.”

Disenfranchised groups often participated in science and technology outside of institutions. For women, that place was the home. Yet although we utilize its many tools and amenities to make our lives easier and more comfortable, the home is not typically regarded as a hotbed of technological advancement. It lies outside our current understanding of technological change—and so, in turn, do women, like Goode, Benjamin, Boone, and Elgin, who sparked that change.

When I asked historian of technology Ruth Schwartz Cowan why domestic technology is not typically recognized as technology proper, she gave two main reasons. First, “[t]he definition of what technology is has shrunk so much in the last 20 years,” she says. Many of us conceptualize technology through a modern—and limited—framework of automation, computerization, and digitization. So when we look to the past, we highlight the inventions that appear to have led to where we are today—which forces us to overlook much of the domestic technology that has made our everyday living more efficient.

The second reason, Cowan says, is that “we usually associate technology with males, which is just false.” For over a century, the domestic sphere has been coded as female, the domain of women, while science, engineering, and the workplace at large has been seen as the realm of men. These associations persist even today, undermining the inventive work that women have done in the domestic sphere. Goode, Benjamin, Boone and Elgin were not associated with any university or institution. Yet they invented new technology based on what they knew through their lived experiences, making domestic labor easier and more efficient.

One can only guess how many other African American women inventors are lost to history because of restricted education possibilities and multiple forms of discrimination, we may never know who they are. This does not mean, however, that women of color were not there—learning, inventing, shaping the places in which we have lived. Discrimination kept the world from recognizing them during their lifetimes, and the narrow framework by which we define technology keeps them hidden from us now.