These Instruments Will Help NASA Figure Out If Life Can Thrive on Europa

The space agency has announced the suite of experiments that will fly on a mission to the icy moon of Jupiter

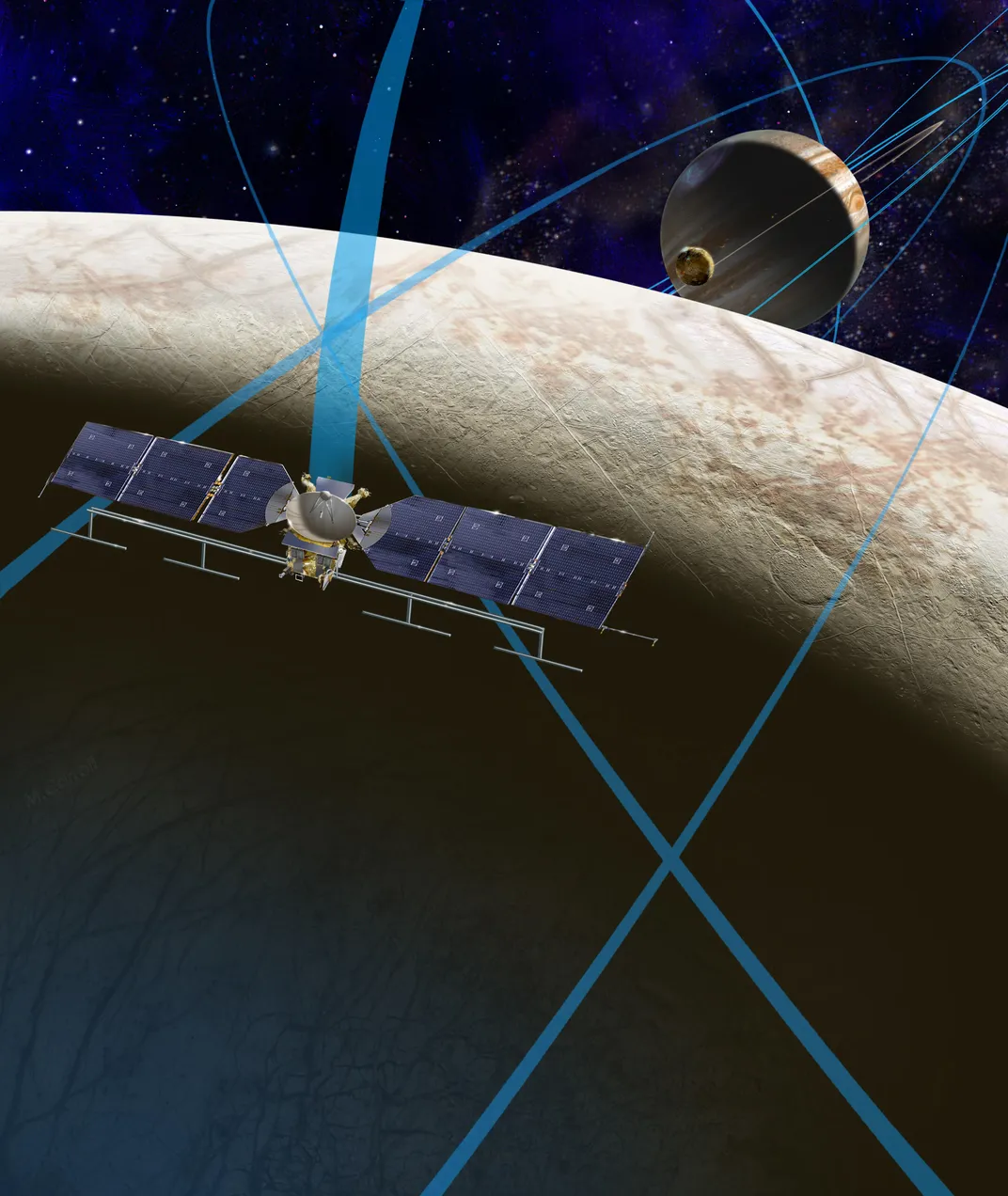

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/4b/c44b9d96-9333-4ecd-af54-708a909b1846/europa_atomic_clock.jpg)

In our pursuit of life beyond Earth, we've spent countless hours and billions of dollars scanning for radio signals from distant exoplanets and probing the dry riverbeds of Mars for signs of ancient fossils. But what if something is alive right now on a world you can see through a backyard telescope?

Today NASA took the first small step in a mission to explore Jupiter's icy moon Europa, one of the most likely places in our solar system for alien life to exist. The space agency has announced nine scientific instruments that will ride on a Europa-bound probe, which will repeatedly fly past the moon. NASA has yet to approve the actual spacecraft design or set a launch date, saying only that the craft could be ready to launch sometime in the 2020s. But the instruments alone are tantalizing, because they are designed to help answer one of the hottest questions in science today: are we alone in the universe?

"Europa is one of those critical areas where we believe the environment is perfect for the potential development of life," Jim Green, director of NASA's planetary science division, said today in a press briefing. "If we do find life or indications of life, that would be an enormous step forward in our understanding of our place in the universe. If life exists in our solar system, and in Europa in particular, then it must be everywhere in our galaxy."

At first glance, Jupiter's moon Europa doesn't look very inviting. It's small, frozen, airless and bathed in a constant haze of lethal radiation from nearby Jupiter. Ask anyone working in planetary science, though, and they will tell you that Europa is perhaps the most provocative destination on NASA's agenda. That's because if anything is essential to life as we know it, it's water, and Europa has bucketfuls.

Early hints of a hidden ocean on Europa prompted Arthur C. Clarke to pen a sequel to 2001: A Space Odyssey in which advanced aliens help protect primitive Europan life from human meddling. Then, in the 1990s, the Galileo spacecraft shocked the scientific establishment when it confirmed that Europa almost certainly has briny depths. Its ocean is anywhere from 6 miles to a few thousand feet below the ice, and it contains about two times as much water as all of Earth's seas combined.

As on Earth, the salty ocean of Europa is sitting on top of a rocky seabed, which could be spewing heat and nutrients into the water. One of Europa's neighboring moons, Io, is the most volcanically active body in the solar system, and according to Green, the Europan seafloor probably looks a lot like the churning, pockmarked surface of Io.

"Hydrothermal vents must represent the volcanoes we see on Io, if indeed Europa has an ocean straddling the entire body," he says. Evidence for these hidden hot spots comes from so-called chaos terrain, disturbed regions on the surface that are covered in brownish gunk. Models suggest these spots are where heat from volcanic vents circulates upward through the water and melts sections of the ice above, allowing some nutrients and organic compounds—the building blocks of life—to escape and coat the surface.

Like Earth's shifting tectonic plates, Europa's icy exterior also seems to be diving back into the liquid layer below in a process called subduction, possibly helping such material cycle through its seas. And most recently, the Hubble Space Telescope caught signs that Europa is sending massive plumes of water into space, akin to the explosive geysers found around Earth's geothermal regions.

It seems the more we look at it, the more Europa resembles a frozen mini-Earth, with all the right ingredients to support organisms in its seas. That has scientists champing at the bit to send out a space probe and try to meet the aliens next door. Support in Congress has added the right dose of political clout, and NASA's 2016 budget includes $30 million for formulating a mission.

All nine instruments will be able to fly on whatever spacecraft NASA selects, Curt Niebur, NASA's Europa program scientist, said during the briefing. The probe will be solar powered and will sweep past Europa at least 45 times, sometimes dipping as low as 16 miles from the surface to collect data. Once in place near the Jovian moon, the mission should last for three years.

The agency received 33 proposals from universities and research institutions across the country for the mission's science instruments, which it has narrowed down to these final selections:

- Plasma Instrument for Magnetic Sounding (PIMS), for determining Europa’s ice shell thickness, ocean depth and salinity.

- Interior Characterization of Europa using Magnetometry (ICEMAG), for measuring the magnetic field near Europa and inferring the location, thickness and salinity of the subsurface ocean.

- Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa (MISE), for identifying and mapping the distribution of organics, salts and other materials to determine habitability.

- Europa Imaging System (EIS), for mapping at least 90 percent of Europa at 164-foot resolution.

- Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface (REASON), an ice-penetrating radar designed to characterize Europa’s icy crust and reveal its hidden structure.

- Europa Thermal Emission Imaging System (E-THEMIS), a “heat detector” designed to help detect active sites, such as potential vents where water plumes are erupting into space.

- MAss SPectrometer for Planetary EXploration/Europa (MASPEX), for measuring Europa’s extremely tenuous atmosphere and any surface material ejected into space.

- SUrface Dust Mass Analyzer (SUDA), for measuring the composition of small, solid particles ejected from Europa and providing the opportunity to directly sample the surface and potential plumes on low-altitude flybys.

- Ultraviolet Spectrograph/Europa (UVS), for detecting small plumes and measuring the composition and dynamics of the moon’s rarefied atmosphere.

These instruments "could find indications of life, but they are not life detectors," Niebur stressed. Planetary experts have been debating the issue, he said, and "what became clear is that we don't have a life detector, because we don't have a consensus on the thing that would tell everybody looking at it, this is alive." But the suite of experiments will help NASA directly sample the icy moon for the first time and better understand its icy crust, its internal composition and the true nature of its elusive plumes. "This payload will help us answer all of these questions," said Niebur, "and take great strides forward in understanding the habitability of Europa."