Things Are Looking Up for Niger’s Wild Giraffes

Wild giraffes are making a comeback despite having to compete for resources with some of the world’s poorest people

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/giraffes_nov08_631.jpg)

In the dry season, they are hard to find. Food is scarce in Niger's bush and the animals are on the move, loping miles a day to eat the tops of acacia and combretum trees. I'm in the back seat of a Land Rover and two guides are sitting on the roof. We're looking for some of the only giraffes in the world that roam entirely in unprotected habitat.

Though it's well over 90 degrees Fahrenheit by 10 a.m., the guides find it chilly and are wearing parkas, and one of them, Kimba Idé, has pulled a blue woolen toque over his ears. Idé bangs on the windshield with a long stick to direct the driver: left, right, right again. Frantic tapping means slow down. Pointing into the air means speed up. But it's hard to imagine going any faster. We are off-road, and the bumps pitch us so high that my seat belt cuts into my neck and my tape recorder flies into the front seat, prompting the driver to laugh. Thorny bushes scraping the truck's paint sound like fingernails on a chalkboard. I don't know what to worry about more: the damage the truck might be causing to the ecosystem or the very real possibility we might flip over.

While Africa may have as many as 100,000 giraffes, most of them live in wildlife reserves, private sanctuaries, national parks or other protected areas not inhabited by humans. Niger's giraffes, however, live alongside villagers, most of whom are subsistence farmers from the Zarma ethnic group. Nomadic Peuls, another group, also pass through the area herding cattle. The "giraffe zone," where the animals spend most of their time, is about 40 square miles, although their full range is about 650 square miles. I've seen villagers cutting millet, oblivious to giraffes foraging nearby—a picturesque tableau. But Niger is one of the poorest, most desolate places on earth—it has consistently ranked at or near the bottom of the 177 nations on the United Nation's Human Development Index—and people and giraffes are both fighting for survival, competing for some of the same scarce resources in this dry, increasingly deforested land.

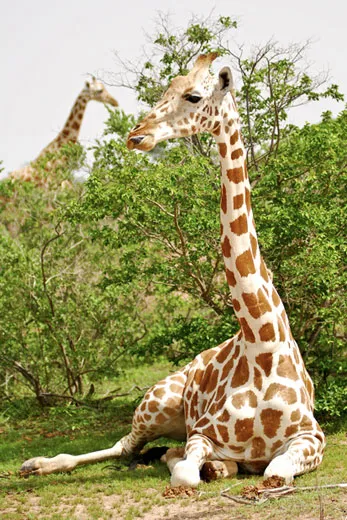

There are nine giraffe subspecies, each distinguished by its range and the color and pattern of its coat. The endangered Giraffa camelopardalis peralta is the one found in Niger and only Niger; it has large orange-brown spots on its body that fade to white on its legs. (The reticulated subspecies, known for its sharply defined chestnut brown spots, is found in many zoos.) In the 19th century, thousands of peralta giraffes lived in West Africa, from Mauritania to Niger, in the semiarid land known as the Sahel. By 1996, fewer than 50 remained because of hunting, deforestation and development; the subspecies was heading for extinction.

That was about the time I first went to Niger, to work for a development organization called Africare/Niger in the capital city of Niamey. I recall being struck by the heartbreaking beauty of the desert, the way people managed to live with so little—they imported used tires from Germany, drove on them until they were bald and then used them as soles for their shoes—and the slower pace of life. We drank mint tea loaded with sugar and sat for hours waiting for painted henna designs to dry on our skin. "I don't know how anyone can visit West Africa and want to live anywhere else in the world," I wrote in my journal as an idealistic 23-year-old.

Two nights a week I taught English at the American Culture Center, where one of my students was a young French ethologist named Isabelle Ciofolo. She spent her days following the giraffes to observe their behavior. She would study the herd for 12 years and was the first to publish research about it. In 1994, she helped found the Association to Safeguard the Giraffes of Niger (ASGN), which protects giraffe habitat, educates the local population about giraffes, and provides microloans and other aid to villagers in the giraffe zone. The ASGN also participates in an annual giraffe census. Which is how I ended up, some 15 years after I first met Ciofolo, in a bucking Land Rover on a giraffe observation expedition that she was leading with Omer Dovi, the Nigerien operations manager for ASGN.

Working on a tip that a large group of giraffes had been spotted the night before, we spend more than two hours looking for them in the bush before we veer off into the savanna. Another hour goes by before Dovi shouts, "There they are!" The driver cuts the Land Rover's engine and we approach the animals on foot: a towering male with large brown spots, two females and three nurslings, which are all ambling through the bush.

The adult giraffes pause and regard us nonchalantly before going back to their browsing. The nurslings, which are only a few weeks old and as frisky as colts, stop and stare at us, batting enormous Mae West eyelashes. Their petal-shaped ears are cocked forward beside their furry horns (which, Ciofolo says, are not really horns but ossicones made from cartilage and covered with skin). Not even the guides can tell if the nurslings are male or female. Once a giraffe matures, the distinction is easy: peralta males grow a third ossicone. The census-takers note three baby giraffes of indeterminate gender.

We watch the statuesque animals galumph forward in the bush. They are affectionate, intertwining necks and walking so closely that their flanks touch. They seem in constant physical contact, and I am struck by how much they seem to enjoy each other's presence.

I ask Ciofolo if she thinks giraffes are intelligent. "I'm not sure how to evaluate the intelligence of a giraffe," she says. "They engage in subtle communication with each other"—grunts, snorts, whistles, bleats—"and we have observed that they are able to figure things out." Ciofolo says a giraffe she named Penelope years ago (the scientists now designate individual animals less personally, with numbers) "clearly knew who I was and had assessed that I was not a threat to her. She let me get quite close to her. But when other people approached, she got skittish. Penelope was able to distinguish perfectly between a person who was nonthreatening and people who represented a potential threat."

A year later, in late 2007, I return to Niger and go into the bush with Jean-Patrick Suraud, a doctoral student from the University of Lyon and an ASGN adviser, to observe another census. It takes us only half an hour to find a cluster of seven giraffes. Suraud points out a male that is closely following a female. The giraffe nuzzles her genitals, which prompts her to urinate. He bends his long neck and catches some urine on his muzzle, then raises his head and twists his long black tongue, baring his teeth. Male giraffes, like snakes, elephants and some other animals, have a sensory organ in their mouth, called Jacobson's organ, that enables them to tell if a female is fertile from the taste of her urine. "It's very practical," Suraud says with a laugh. "You don't have to take her out to dinner, you don't have to buy her flowers."

Although the female pauses to let the male test her, she walks away. He does not follow. Presumably she is not fertile. He meanders off to browse.

If a female is fertile, the male will try to mount her. The female may keep walking, causing the male's forelegs to fall awkwardly back to the ground. In the only successful coupling Suraud has witnessed, a male pursued a female—walking alongside her, rubbing her neck, swaying his long body to get her attention—for more than three hours before she finally accepted him. The act itself was over in less than ten seconds.

Suraud is the only scientist known to have witnessed a peralta giraffe give birth. In 2005, after just six months in the field, he was stunned when he came upon a female giraffe with two hoofs sticking out of her vagina. "The giraffe gave birth standing up," he recalls. "The calf fell [six feet] to the ground and rolled a bit." Suraud smacks the top of the truck to illustrate the force of the landing. "I'd read about it before, but still, the fall was brutal. I remember thinking, ‘Ouch, that's a crazy way to come into the world.'" The fall, he goes on, "cuts the umbilical cord in one swift motion." Suraud then watched the mother lick the calf and eat part of the placenta. Less than an hour later, the calf had nursed and the two were on the move.

Though mother and calf stay together, groups of giraffes are constantly forming and re-forming in a process scientists call fission-fusion, similar to chimpanzee grouping. It is as common for half a dozen males to forage together as it is for three females and a male. In the rainy season, when food is plentiful, you might find a herd of 20 or more giraffes.

Unlike with chimps, however, it is almost impossible to identify an alpha male among giraffes. Still, Suraud says he has seen male giraffes mount other males in mock copulation, often after a fight. He's not sure what to make of the behavior but suggests it may be a type of dominance display, though there doesn't seem to be an overarching power hierarchy.

Competition among males—which grow to 18 feet tall and weigh as much as 3,000 pounds—for access to females, which are slightly smaller, can be fierce. Males sometimes slam each other with their necks. Seen from afar, a fight might look balletic, but the blows can be brutal. Idé says he witnessed a fight several years ago in which the vanquished giraffe bled to death.

As it happens, the evolution of the animal's neck is a matter of some debate. Charles Darwin wrote in The Origin of Species that the giraffe is "beautifully adapted for browsing on the higher branches of trees." But some biologists suggest that the emergence of the distinctive trait was driven more by sexual success: males with longer necks won more battles, mated more often and passed on the advantage to future generations.

Still, wild giraffes need a lot of trees. They live up to 25 years and eat from 75 to 165 pounds of leaves per day. During the dry season, Niger's giraffes get most of their water from leaves and the morning dew. They're a bit like camels. "If water is available, they drink and drink and drink," says Suraud. "But, in fact, they seem not to have a need for it."

Dovi points out places in the savanna where villagers have cut down trees. "The problem is not that they take wood for their own use; there's enough for that," he says. "The problem is that they cut down trees to sell to the market in Niamey."

Most woodcutting is prohibited in the giraffe zone. But Lt. Col. Kimba Ousseini, commander of the Nigerien government's Environmental Protection Brigade, says people break the law, despite penalties of between 20,000 and 300,000 CFA francs (approximately $40 to $600) as well as imprisonment. He estimates that 10 to 15 people are fined each year. Yet wood is used to heat houses and fuel cookfires, and stacks and stacks of spindly branches are for sale at the side of the road to Niamey.

When you walk alongside the towering giraffes, close enough to hear the swish-swish of their tails as they gambol past, it's hard not to be indignant about the destruction of their habitat. But Zarma villagers cut down trees because they have few other ways to make money. They live off their crops and are totally dependent on the rainy season to irrigate their millet fields. "Of course they understand why they shouldn't do it!" Ousseini says. "But they tell us they need the money to survive."

The ASGN is trying to help the giraffes by making small loans to villagers and promoting tourism and other initiatives. In the village of Kanaré, women gathered near a well constructed with ASGN funds. By bringing aid to the region in the name of protecting giraffes, ASGN hopes the villagers will see the animals as less of a threat to their livelihood. A woman named Amina, who has six children and was sitting in the shade on a wire-and-metal chair, says she benefited from an ASGN microloan that enabled her to buy goats and sheep, which she fattened and sold. "Giraffes have brought happiness here," Amina says in Zarma through an interpreter. "Their presence brings us lots of things."

At the same time, giraffes can be a nuisance. They occasionally eat crops such as niebe beans, which look like black-eyed peas and are crushed into flour. (We ate tasty niebe-flour beignets for breakfast in a village called Harikanassou, where we spent the night on thin mattresses under mosquito nets.) Giraffes splay their legs and bend their long necks to eat mature beans right before harvest. They also forage on the succulent orange mangoes that ripen temptingly at giraffe-eye height.

The villager's feelings about the giraffes, from what I gather after speaking with them, are not unlike what people in my small town in southern Oregon feel about deer and elk: they admire the animals from a distance but turn against them if they raid their gardens. "If we leave our niebe in the fields, the giraffes will eat it," explains Ali Hama, the village chief of Yedo. "We've had problems with that. So now we harvest it and bring it into the village to keep it away from the giraffes." Despite having to do this extra step, Hama says his villagers appreciate the giraffes because the animals have brought development to the region.

Unlike giraffes in other parts of Africa, Niger's giraffes have no animal predators. But they face other dangers. During the rainy season, giraffes often come to the Kollo road, about 40 miles east of Niamey, to nibble on shrubs that spring from the hard orange earth. On two occasions in 2006, a bush taxi hit and killed a giraffe at dusk. No people were injured, but the deaths were a significant loss to the small animal population. Villagers feasted on the one-ton animals.

The Niger government outlaws the killing of giraffes, and Col. Abdou Malam Issa, a Ministry of the Environment official, says the administration spends about $40,000 annually on anti-poaching enforcement. In addition, Niger has received money from environmental groups around the world to support the giraffes. As a result, giraffes face little danger of being killed as long as they stay within Niger. But when a group of seven peraltas strayed into Nigeria in 2007, government officials from Niger were unable to alert Nigerian officials quickly enough. Villagers killed one of the giraffes and ate it.

Niger's government hasn't always been disposed to help the giraffes. In 1996, after seizing power in a coup d'état, Ibrahim Baré Mainassara wanted to give two giraffes each to the presidents of Burkina Faso and Nigeria. When the forestry service refused to help him capture the giraffes, Baré sent in the army. More than 20 giraffes were killed, out of a total population of fewer than 60. "We lost 30 percent of the herd," says Ciofolo, who was working in the field at that time. In 2002, President Mamadou Tandja, who was first elected in 1999 and remains in power, set out to give a pair of giraffes to Togo's president. This time the Togolese Army, helped by local villagers and the forestry service, spent three days chasing the giraffes and captured two. One died en route to Togo, and the other after arriving there. Hama Noma, a 27-year-old villager who witnessed the capture, says the giraffes were immobilized with ropes and transported in the back of a truck: "They suffered a lot before they died."

Driving north past a pitted and rusty sign for the town of Niambere Bella, we come across a lone male strutting through the fields. "Number 208!" Suraud cries out. "This is only the second time I've seen him!" We find a group of 16 giraffes, an unusual sight during the dry season. Each one has been identified previously, which makes the research team rejoice. "It means we haven't missed any," says Suraud, clearly pleased. He pats Idé on the back, smiling. The mood is hopeful—at least 21 calves have been born recently, more than expected. And indeed the official results are heartening: 164 giraffes were photographed in 2007, leading the researchers to estimate that the population is around 175 individuals. While that number is dangerously small, it's up from 144 in 2006 and represents a 250 percent increase since 1996. Suraud says he is optimistic about the herd.

Julian Fennessy, a founding member of the International Giraffe Working Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, projects that a minimum of 400 giraffes of a variety of ages is needed for a viable peralta population. Whether the mostly desert climate of this part of West Africa can support the growing number remains to be seen; some giraffe researchers have even suggested that the giraffes might be better off in a wildlife refuge. But Ciofolo points out that the nearest reserve in Niger has unsuitable vegetation—and lions. "In my opinion, giraffes are much better off living where they are now, where they are protected by the local people," she says.

As the sky darkens, we drive past several villagers using handmade machetes called coup-coups to cut dried millet stalks. A father and son lead two bulls pulling a cart laden with straw bales along rough track in the bush. Now the royal blue sky is streaked with orange and violet from the setting sun, and the moon shimmers. Nearby, a group of foraging giraffes adds a calm majesty to the landscape these animals have so long inhabited.

Jennifer Margulis lived in Niger for more than two years and now writes about travel and culture from Ashland, Oregon.