What a Tiny Fish Can Tell Us About How Humans Stood Upright

What is the root of why our ancestors gained the power to walk on two feet and chimpanzees didn’t?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/1c/211cf869-7177-4688-a6b0-97204a5df1aa/apr2016_i01_phenom.jpg)

You’d think that the latest leap forward in our understanding of human locomotion would come from studying feet. Yet scientists have discovered a surprising new clue to the origins of human bipedalism in a commonplace, pinkie-size fish.

Analyzing the DNA of the threespine stickleback, researchers led by David Kingsley, a biologist at Stanford University, identified a so-called genetic enhancer, a kind of volume control knob that works during body development to help sculpt the bony plates that cloak the stickleback in lieu of scales. The enhancer modulates the release of a bone-related protein known as GDF6, turning it up or down to alter the plates to suit the fish’s setting. For marine sticklebacks that live in open water with a multitude of toothy predators, the enhancer spins out enough GDF6 protein to help build hefty protective plates. But freshwater sticklebacks do better to dart off and hide, and so, through enhancer-driven twiddling of protein release, those fish end up with slimmer and more pliable plates.

A genetic toggler’s response varies from one setting to the next, while its target—the brick-and-mortar proteins—remains the same, lending evolution considerable flexibility. “It’s such a good mechanism for evolving traits that you see it used over and over,” Kingsley says.

When the researchers explored the role of the GDF6 protein and its enhancers in shaping the bones of mammals, including the chimpanzee, our nearest genetic kin, they found an enhancer that affected development of rear limbs but not forelimbs. The gene’s greatest impact was on the length and curvature of the toes. In human DNA, however, the enhancer was deleted.

That single genetic change could help explain important differences between a chimpanzee foot and our own—and how our ancestors gained the power to rise up and walk on two feet. A chimpanzee’s toes are long and splayed, and its big-toe equivalent pulls away from the other digits like a thumb: a prehensile foot designed for quick climbing. By contrast, in the human foot, the sole is enlarged while the bone of the big toe is thickened and aligned with the other, now-foreshortened toes: This is a sturdy platform, able to support an upright load in motion.

Aside from showing that our big toe deserves far more respect than most of us know, the new finding demonstrates that minor alterations in DNA can have profound evolutionary impacts, and that nature is a tireless recycler and collage artist, mixing and matching a few favorite techniques to generate a seemingly bottomless diversity of forms.

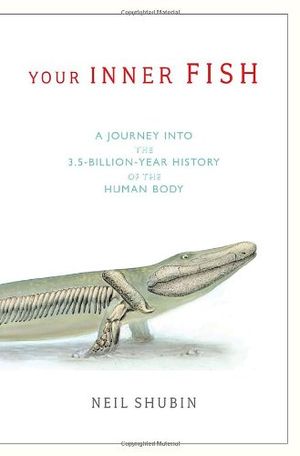

“Our shared history with fish,” says Neil Shubin, author of Your Inner Fish and a paleontologist, “makes them a wonderful arena for exploring the fundamentals of our own bodies.”

Your Inner Fish