Today’s Whales Are Huge, But Why Aren’t They Huger?

Most giant cetaceans only got giant in the past 4.5 million years, suggesting they could have room to grow

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/5b/305b39ab-01a5-4e77-bcce-fe7dd7b34360/cf7eac.jpg)

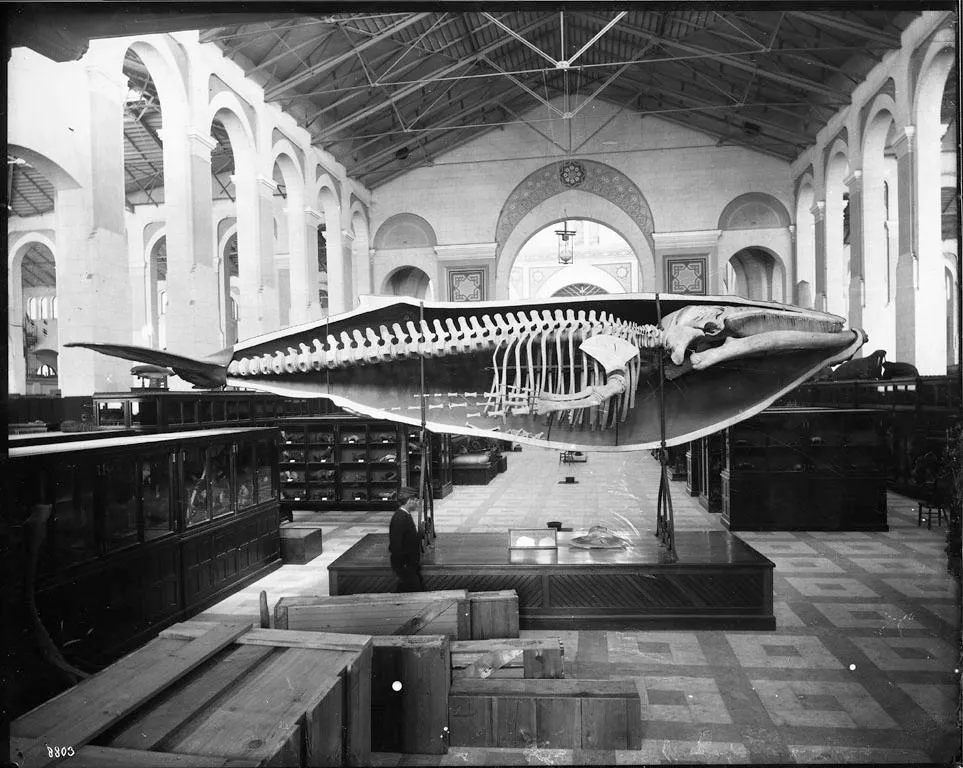

We live in an age of giants. That might sound strange, given the lack of enormous dinosaurs or giant ground sloths trundling around. But it’s true: The blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus, is the largest animal that has ever lived, stretching over 100 feet long and weighing about 100 tons. And this giant isn’t some holdover from an ancient epoch.

Today’s enormous whales are the result of a relatively recent evolutionary growth spurt.

It’s easy to take the vastness of many whales for granted, but from an evolutionary scientist’s perspective, the fact that they evolved to be so gargantuan seems fairly unlikely. Nicholas Pyenson, the curator of fossil marine mammals at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, has been tracking the long tail of whale evolution for decades, from deserts brimming with bones to the seas themselves.

Part of the story in his new book, Spying on Whales, is documenting how today’s ocean giants came to be as giant they are.

“Whales have a geologic history spanning over 50 million years,” Pyenson says, “but they really didn’t reach titanic sizes until the past few million years.” What we know of whales’ fossil backstory makes cetaceans over 200,000 pounds—like today’s blue, fin, bowhead, and right whales—relatively new. So how did this happen?

First of all, it’s not as if just one lineage of whale got big in a straightforward fashion. “We know from looking at the family tree of big whales that many different lineages reach extreme sizes independently,” Pyenson says. But there’s a pattern in when these various whales got supersized. Extremely large whales evolved in the last 4.5 million years, coinciding with the ebb and flow of the Ice Ages.

Ice Age conditions were a boon to filter-feeding whales, meaning that the advent of an Ice Age generally heralded a growth spurt. “The boost from nutrient run-off along the coasts make for hyperabundant prey in warmer seasons,” Pyenson says, “which is something we see today off Alaska, California or Maine.” This not only offered a smorgasbord for whales, but also gave whales a reason to migrate long distances to take advantage of the seasonal bounty. “Ice Age seas made big whales even bigger.”

Listen to this episode of Sidedoor, the Smithsonian podcast, that takes a deep dive into the once aggressively hunted and thought to be nearly extinct, gray whale. They've rebounded to become one of the North Pacific’s most abundant whale species. What changed?

And aside from the sea changes that occurred during the Pliocene and Pleistocene, the specifics of living in the marine realm allowed some whales reach sizes unheard of for land animals. “Fully aquatic animals live in a nearly neutrally buoyant environment,” Mont Sinai anatomist Joy Reidenberg says, “so their weight is irrelevant.” This is why a whale is far heavier than a dinosaur of the same size; Supersaurus, estimated at about the same length as the largest blue whale, weighed less than half as much. It’s also why beached whales quickly find themselves in danger: On land, a whale’s bulk damages their muscles and releases dangerous amounts of a protein called myoglobin that can cause their kidneys to fail.

Still, this doesn’t mean that, anatomically, anything goes in the ocean. “You might imagine that whales could simply evolve larger and larger sizes unconstrained,” Pyenson says, “but there are a lot of fact of their lives that do pose biological limits.”

Early on, Reidenberg says, the amphibious mammals that preceded today’s whales spent their time between the shore and shallow water. They needed dense bones to act as ballast to help keep them neutrally buoyant and also support themselves while on shore leave.

As whales became more aquatic and attained huge sizes, though, the pattern reversed. Modern whales, Reidenberg says, “have porous bones that, combined with fat deposits, make them lighter.” This helps whales stay at the surface and breathe air, and, Reidenberg points out, the balance of heavy and light organs inside whales allows them to change how buoyant they are by expanding or contracting air spaces in organs like the lungs and larynx. When whales blow air (and snot) out of their blowholes, they’re controlling their buoyancy.

These recent, extreme adaptations raise a question of how cetaceans may continue to change. With the largest whale of all time still swimming the seas today, could giant whales get even bigger still?

While it’s tantalizing to think of even larger leviathans, there are a few things that prevent whales from being more massive. Whales breathe air, just as their amphibious ancestors did back in the Eocene, making their lungs critical hardware for animals that have to deal with vast differences in ocean pressure. But there are limits to how efficiently respiratory systems can provide sufficient oxygen to larger and larger bodies, Pyenson notes, “and that may be one reason that there aren’t, say, 300-foot-long whales in the oceans today.”

The physics of aquatic life comes into play, too. Whales have streamlined bodies to help reduce drag (the force that resists a whale’s motion through the water) but there’s no way to eliminate it entirely. And the feeding methods of the largest whales—gulping huge mouthfuls of small morsels out of the water—only works if whales are able to overcome this problem as they literally drag their jaws through the water.

A 2012 study of this feeding behavior found that, beyond lengths of 110 feet, baleen whales wouldn’t be able to overcome the drag to close their mouths fast enough to capture fleeing prey. “The largest whales ever measured, at 109 feet, are pushing the theoretical limit of the largest gulp-feeding whales that can exist.” In other words, whales probably won’t be able to get much larger without an overhaul of the way the largest species feed.

Spying on Whales: The Past, Present, and Future of Earth's Most Awesome Creatures

A dive into the secret lives of whales, from their evolutionary past to today's cutting edge of science.

Human history has played a role, too. “Industrial whaling added another selective pressure to whale populations,” Reidenberg says. He adds both modern and historic whalers have regularly targeted the largest whales they could find, meaning that “smaller whales that could reproduce at a smaller size were artificially selected [for].” Hunting whales may have shrunken the whale populations that managed to survive, and, for slow-reproducing species, even limited whaling can still have dramatic effects.

What the future holds for whales, then—as with so much of our planet—depends very much on our how our species decides to act.

Life on Earth is facing a major extinction crisis, and, Pyenson points out, research on extinction risk factors in mammals often points to large body size as a liability. This is as true for whales as for elephants and long-lost species like wombats the size of small cars. The North Atlantic right whale, for example, reaches over 50 feet in length and is one of the most endangered cetaceans on the planet.

How this will play out for other whales is uncertain, but Pyenson notes that there are plenty of risks beyond whaling. “Hundreds of thousands die from net entanglements, fisheries by-catch, poisoning from pollution, or by ship-strike,” Pyenson says, which is not to mention the obscene levels of microplastic pollution in the oceans. How the massive amount of plastic garbage affects the health of filter-feeding whales is unknown, Pyenson says, and that’s worrying as researchers try to beat extinction.

Some giants have managed to bounce back, such as humpbacks and West Coast gray whales. But the threats many cetaceans face—from the tiny, highly-imperiled vaquita to the blue whale itself—require that researchers dig through petrified boneyards as well as sift the seas to better understand how to save cetaceans in unstable oceans. Fossils have shown when whales got big, and biology has revealed how they’ve set the upper limit for animal size, but the fantastic whales of future seas will only exist if we make an effort to save them now.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)