Top Nine Ocean Stories That Had Us Talking in 2015

From fossil whales to adorable octopuses, here are some of the marine headliners that caught our attention this year

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/79/52799a98-c73a-4102-bb68-1bbcd06adee6/42-79426835.jpg)

It’s been a year of extremes for Earth's oceans, and many were not good. But there are stories that balance the bad news with reasons for #OceanOptimism about the year ahead.

We learned a lot this year about how animals use their senses under the water. Mantis shrimp, which have built-in polarized lenses, are able to send each other messages with twisted light that only other mantis shrimp can see. Salmon moving upstream can flip a biological switch that allows them to see infrared light. Chitons, which don’t look like much more than a bump on an ocean rock, build thousands of eyes into their hard shells, while octopuses can sense light levels with their skin. And the Navy is interested in a discovery that explains how some fish manage the ultimate sensory trick of making themselves nearly invisible.

When it comes to the sea, sound travels much farther than light. The skulls of baleen whales actually channel the frequencies of the whale songs they hear underwater, sending them right to their ear bones.

Small Plastics Are a Big Problem

We know the ocean is full of plastic, most famously in the eastern Pacific garbage patch and in the stomachs of birds. But what about the plastic we can’t see?

This year we learned that our synthetic clothes and sportswear are leaching their plastic threads into water systems every time we run a wash cycle. Tiny plastic microbeads—used as exfoliators in facewash, toothpaste and other personal products that help keep our skin soft and our teeth clean—are also making their way to our water. Both the strings and beads are too small to be filtered out by water treatment systems. Found in rivers, streams, lakes and the ocean, these incredibly tiny pieces of plastic are now an unintended staple in the diets of mammals, fish and plankton. They can clog up corals and leach chemicals into the fish.

In response to the problem, several states have passed legislation that would phase out microbead use in the coming years. Now a bill approved by Congress and sent to the president would speed up that process nationwide. You can support the overarching cause by donning a shoe made of recycled ocean plastic—a step in the right direction for sure.

Poop to the Rescue

Poop can be more than just a byproduct of digestion. Unsurprisingly, the largest animal on earth—the blue whale—produces a significant amount of excrement that is typically released at the ocean’s surface and helps stimulate plankton growth. But the loss of blue whales and other large whale species over the past century, due mostly to hunting, means that the oceans have lost a significant pathway for recycling nutrients. Will “Save the Whale Poop to Save the Oceans,” as suggested by Maddie Stone at Gizmodo, be the next conservation slogan?

The plankton populations that bloom from whale poop at the ocean surface of course poop themselves. This poop makes up a portion of what scientists call marine snow—a general term that encompasses dead organisms, feces and other organic matter. Scientists are now learning how much carbon sinks to the bottom of the sea thanks to marine snow, effectively removing it from the climate change equation.

Back on land, penguins need rocky locations free of ice to lay their eggs, and this year citizen scientists poring over hours of mundane video footage helped discover a key ingredient to their success. That’s right, their poop! Scientists think groups of pooping penguins speed up the melting of ice, allowing them to start laying eggs earlier.

Which Fish Am I Eating?

We don’t really know what types of fish we are eating—that’s what study after study has found. This is true for many species, including salmon, where mislabeling of farm-raised versus wild-caught fish can leave us pulling out our hair. Now, we’ll have a third choice—the FDA this year approved commercial sales of genetically engineered salmon.

What does that really mean? The fish are engineered to grow fast and get big when raised in their indoor environment. The approval process took two decades, and genetically altered salmon seem to be safe to eat, but negative effects on the environment are harder to rule out.

Hot, Hot, Hot

It’s official: This year’s El Niño is the strongest on record—meaning that water in the Pacific Ocean is the hottest we’ve ever seen, bringing with it deadly heat waves, floods and droughts. Blooms of algae grow in these warm conditions, and ocean mixing is disturbed, leaving many animals without their usual food sources and poisoning others. The El Niño, plus generally warmer waters from climate change, has also spurred the third global coral bleaching event ever recorded.

Global warming means that glaciers are surrounded: warm air from above, warm water below, and small rivulets of water going right through them. All of this means that Greenland’s glaciers are melting at record speeds. As Arctic ice is seeing all-time lows due to the warming, Antarctic ice is increasing. But there is a net loss for global sea ice. Not to mention, it’s only a matter of time until the unstable West Antarctic ice sheet moves into the sea.

Rapid melting can threaten sea life and also seed the growth of certain plankton species, putting ecosystems out of whack. While it’s no surprise some of the tiniest things in the ocean would be impacted by all this melt, such large-scale changes can even alter the rotation of the Earth.

Animals (and Plants) On the Move

Despite strict fishing limits on cod in New England waters in place since 2013, the fish are just not coming back. The restrictions may have come too late, as 2015 brought news that the U.S. fishery is not rebounding. The problem? The warming waters mentioned previously are not only causing sea level rise and coral bleaching, but are also triggering species to move outside of their typical ranges and making it hard for juvenile fish to survive—even causing adult cod to die.

The increased water temperatures are not just impacting cod stocks—pink sea slugs in the Pacific are moving north, blob-like creatures called sea hares are taking over California beaches, walruses are crowding Alaskan shores, king crabs are invading Antarctica and there are increasing instances of large species, like whales, seen on the other side of the world from where they are usually found.

Massive influxes of sargassum, a brown seaweed, have been taking over the shorelines of the Caribbean. The unprecedented amount of sometimes-stinky seaweed turned away some tourists and in some instances reached heights of ten feet.

The good news? The cod stocks in Canada seem to be doing well, which means if we manage species properly, there is hope.

Skeletons in the Closet

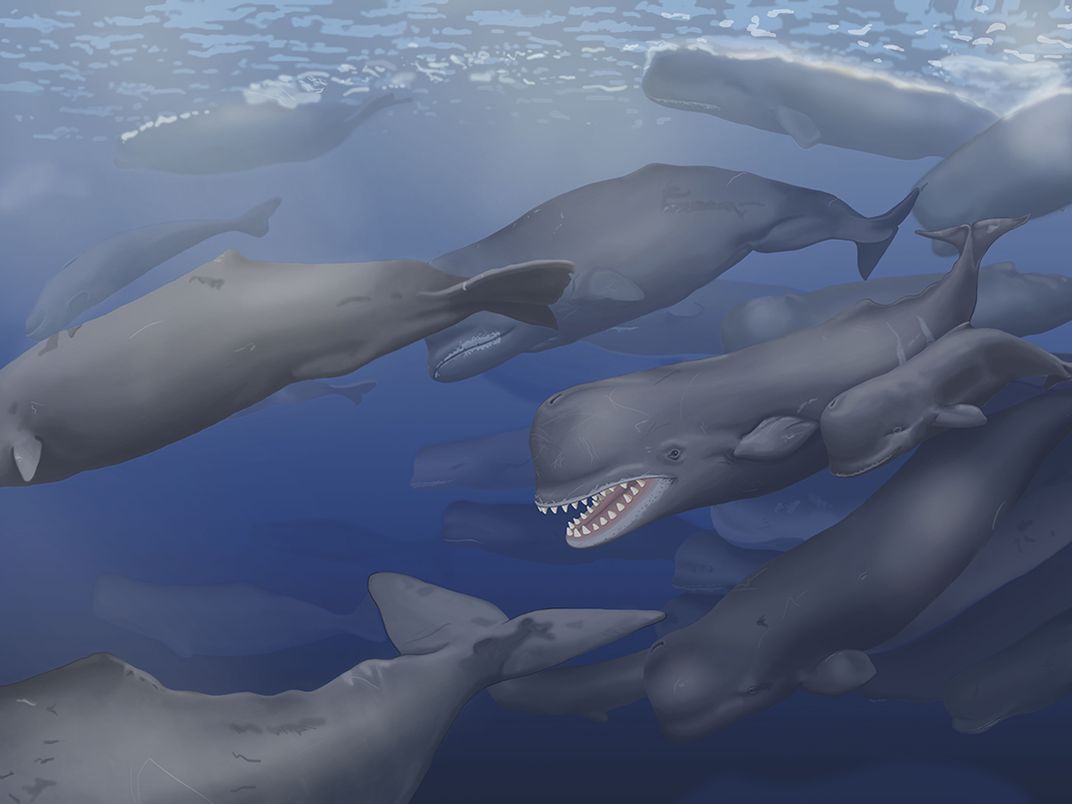

Among the fossil findings of 2015, this one was a seriously amazing tale. A mostly forgotten skull long thought to be from an extinct group of walruses is actually from a new group in the sperm whale family. Smithsonian scientists scanned and digitized the hefty 300-pound fossil 90 years after it was first described, piqued by the shapes of the teeth that just didn’t add up.

Elsewhere, a newfound sea urchin fossil was shown to be the oldest of its kind—moving its branch in the family tree of invertebrates back a full 10 million years.

For some groups there are no fossils, but that doesn’t mean we can’t reconstruct their history. An entirely new microbe was discovered from DNA in Arctic sea floor sediment. The new microbial phylum may be the closest living relative to an ancestral cell that swallowed a bacterium and began the journey to a more complicated cellular world—including us!

Species We Barely Know

New ocean species get discovered on a regular basis and it’s hard to know just how many species there are still waiting in the depths. No wonder, when even old friends can be hard to find. A rare squid mugged for the camera, and for the first time since its discovery 30 years ago, we caught a glimpse of the enigmatic fuzzy nautilus. Some creatures help us by lighting the way—fluorescent animals were everywhere in the news this year. A glowing sea turtle wowed us, followed by brightly lit eels and deep-sea sharks.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Some species are so new to science they don’t even have names yet: What might be the world’s cutest octopus laid nine eggs for scientists and just might wind up being called Opisthoteuthis adorabilis.

A New Hope

Last, but certainly not least, there was some major movement forward this year in the realization that we must work together to preserve our planet and its seas.

Pope Francis raised the environmental alarm with his encyclical in June that urged individuals and governments to take action. The document specifically called out melting sea ice, ocean acidification and coral reef biodiversity, among other ocean issues. His call to action may be the push needed.

The Pope continued this call as the United Nations’ Climate Change Conference—or COP21—occurred in Paris this December. The negotiations were successful, and the groundbreaking document that resulted calls for keeping the increase in global average temperature “well below 2 degrees Celsius [3.6 degrees Fahrenheit]” through reductions in fossil fuel emissions. Even better, despite being initially ignored, the oceans are now included in the agreement by name.

And it’s not just the climate front that is seeing progress. Chile, Palau, New Zealand and the U.K. all expanded the ranges of their surrounding oceans that are fully protected. In Palau, this amounts to a whopping 80 percent of its territorial waters. The U.S. is also expanding its marine sanctuaries, approving the first new sites to be designated in 15 years.

Learn more about the seas with the Smithsonian Ocean Portal.

Learn more about the seas with the Smithsonian Ocean Portal.