Top Ten Stories About Sharks Since the Last Shark Week

Shark tourism, cannibalistic shark embryos, wetsuits designed to camouflage from sharks and more

![]()

Illegal shark fishing along with increasing demand for shark fin soup has led to the removal of 95% of endangered scalloped hammerheads from the ocean. Photo by Jeff Litton/Marine Photobank

People have been fascinated and terrified by sharks for thousands of years, so you would think that we know a fair bit about the roughly 400 named species that roam the ocean. But we have little sense of how many sharks are out there, how many species there are, and where they swim, let alone how many existed before the advent of shark fishing for shark fin soup, fish and chips, and other foods.

But we are making progress. In honor of Shark Week, here’s an overview of what we have learned about these majestic citizens of the sea in the past year:

1. Sharks mostly come in shades of gray, and it’s likely that they only see that way as well. Now, that knowledge is being put to use to protect surfers and swimmers offshore. In 2011, researchers from the University of Western Australia found that, out of 17 shark species tested, ten had no color-sensing cells in their eyes, while seven only had one type. This likely means that sharks hunt by looking for patterns of black, white and grey rather than noticing any brilliant colors. To protect swimmers, whose bodies often look like a tasty seal from below, the researchers are working with a company to design wetsuits that are striped in colorblocked disruptive patterns. One suits will alert sharks that they aren’t looking at their next meal, and a second suit that will help camouflage swimmers and surfers in the water.

2. The thresher shark has a long, scythe-shaped tail fin that scientists long-suspected was used for hunting, but they didn’t know how. This year, they finally filmed how the thresher shark uses it to “tail slap” fish, killing them on impact. It herds and traps schooling fish by swimming in increasingly smaller circles before striking the group with its tail. This strike usually comes from above instead of sideways, an unusual technique that allows the shark to stun multiple fish at once—up to seven, the study found. Most carnivorous sharks only kill one fish at a time and so are comparatively less efficient.

3. How many sharks do people kill each year? A new study published in July 2013 used available shark catch information to estimate the global number—a staggering 100 million sharks killed every year. Although the data are incomplete and often do not include those sharks whose fins are removed and bodies are thrown back to sea, this is the most accurate estimate to date. Slow growth and low birth rates of sharks mean that they are not able to repopulate fast enough to catch up with the loss.

4. The 50-foot giant megalodon shark is a staple of shark week, reigning as the great white’s larger and even more terrifying ancestor. But a new fossil discovered in November turns that supposition on its head: it looks like the megalodon isn’t a great white shark ancestor after all, but is more closely related to the fish-munching mako sharks. The teeth of the new fossil look more like great white and ancient mako shark teeth than megalodon teeth, which also suggests that great whites are more closely related to mako sharks than previously thought.

Sharks are worth more alive, generating tourist dollars, than dead on a plate. Photo by Ellen Cuylaerts/Marine Photobank

5. Sharks are worth more alive in the water than dead on the plate (or bowl). In May, researchers found that shark ecotourism ventures—such as swimming with whale sharks and coral reef snorkeling—bring in 314 million U.S. dollars globally every year. What’s more, projections show that this number will double in the next 20 years. In contrast, the value of fished sharks is estimated at 630 million U.S. dollars and has been declining for the past decade. While dead sharks’ value terminates after they are killed and consumed, live sharks provide value year after year: in Palau, an individual shark can bring up to 2 million dollars in benefits over its lifetime from the tourist dollars that pour in just so that people can view the shark up close. One citizen science endeavor even has snorkeling travelers snapping photos of whale sharks in an effort to help researchers. Protecting sharks for future ecotourism endeavors just makes the most financial sense.

6. Bioluminescence isn’t just for jellyfish and anglers: even some sharks are able to light up to confuse predators and prey alike. Lanternsharks are named for this ability. It’s been long known that their bellies light up to blend in with sunlight shining down from above, an adaptation known as countershading. But in February, researchers reported that lanternsharks also have “lightsabers” on their backs. Their sharp, quill-like spines are lined with thin lights that look like Star Wars weaponry and send a message to predators that, “if you take a bite of me, you might get hurt!”

7. What can an old sword tell us about sharks? Far more than you might expect—especially when those swords are made of shark teeth. The swords, along with tridents and spears collected by Field Museum anthropologists in the mid-1800s from people living in the Pacific’s Gilbert Islands, are lined with hundreds of shark teeth. The teeth, it turns out, come from a total of eight shark species—and, shockingly, two of these species had never been recorded around the islands before. The swords give a glimpse into how many more species once lived on the reef, and how easy it is for human memory to lose track of history, a phenomenon known as “shifting baselines.”

Even as embryos in an egg case, bamboo sharks can sense the electrical fields given off by predators and freeze to avoid detection. Photo by Ryan Kempster

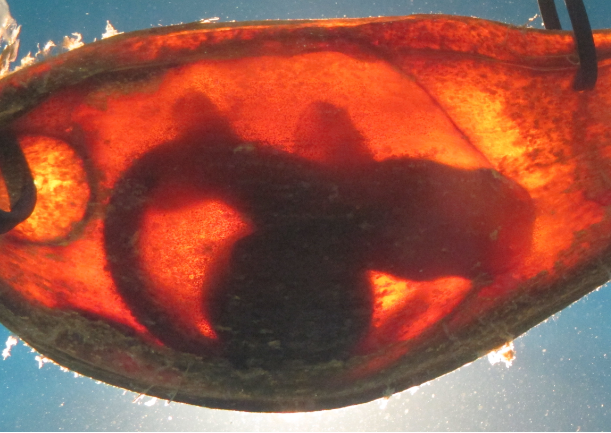

8. Sharks know some pretty neat tricks even before they’re born. Bamboo shark embryos develop in egg cases that float on the high seas, where they are vulnerable to being eaten by all manner of predators. Even as developing embryos, they can sense electric fields in the water given off by a predator—just like adults. If they sense this danger nearby they can hold still, even stopping their breathing, so they won’t be noticed in their egg cases. But for sand tiger shark embryos, which develop inside the mother, their siblings can pose the biggest threat—the first embryos to hatch from eggs, at just roughly 100 millimeters long, will attack and devour their younger siblings.

9. Shark fin soup has been a delicacy in China for hundreds of years, and its popularity has only increased in the last several decades with the country’s growing population. This increasing demand has heightened the number of sharks killed every year, but the expensive dish may be losing some fans.

Even before last year’s Shark Week, the Chinese government banned the serving of shark fin soup at official state banquets—and the conversation hasn’t died down since. Countries and states banning the trade of shark fins and regulating the practice of shark finning have made headlines this year. And just a few weeks ago, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed a ban of the possession and sale of shark fins in the state that will go into effect in 2014.

10. Shark fin bans aren’t the only method of protecting sharks. The island nations of French Polynesia and the Cook Islands created the largest shark sanctuary in December of 2012—protecting sharks from being fished in an area of over 2.5 million square miles in the south Pacific Ocean. And member countries of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) voted to place export restrictions on five species of sharks in March 2013. Does this mean that the general perception of sharks is changing for the better and that the public image of sharks is veering away from its “Jaws” persona? That, in essence, is up to you!

–Emily Frost, Hannah Waters and Caty Fairclough co-wrote this post

Learn more about sharks at the Smithsonian’s Ocean Portal.

Learn more about sharks at the Smithsonian’s Ocean Portal.