Tracking the Elusive Lynx

Rare and maddeningly elusive, the “ghost cat” tries to give scientists the slip high in the mountains of Montana

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lynx-Montana-631.jpg)

In the Garnet Mountains of Montana, the lynx is the king of winter. Grizzlies, which rule the wilderness all summer, are asleep. Mountain lions, which sometimes crush lynx skulls out of spite, have followed the deer and elk down into the foothills. But the lynx—with its ultralight frame and tremendous webbed feet—can tread on top of the six-foot snowpack and pursue its singular passion: snowshoe hares, prey that constitutes 96 percent of its winter diet.

Which is why a frozen white bunny is lashed to the back of one of our snowmobiles, alongside a deer leg sporting a dainty black hoof. The bright yellow Bombardier Ski-Doos look shocking against the hushed backdrop of snow, shadows and evergreens. Lynx (Lynx canadensis) live on the slopes of these mountains, a part of the Rockies, and the machines are our ticket up. We slide and grind on a winding trail through a forest shaggy with lichen; a bald eagle wheels above, and the piney air is so pure and cold it hurts my nose. “Lean into the mountain,” advises John Squires, the leader of the U.S. Forest Service’s lynx study at the Rocky Mountain Research Station in Missoula. I gladly oblige, as this means leaning away from the sheer cliff on our other side.

The chances that we’ll trap and collar a lynx today are slim. The ghost cats are incredibly scarce in the continental United States, the southern extent of their range. Luckily for Squires and his field technicians, the cats are also helplessly curious. The study’s secret weapon is a trick borrowed from old-time trappers, who hung mirrors from tree branches to attract lynx. The scientists use shiny blank CDs instead, dabbed with beaver scent and suspended with fishing line near chicken-wire traps. The discs are like lynx disco balls, glittering and irresistible, drawing the cats in for a closer look. Scientists also hang grouse wings, which the lynx swat with their mammoth paws, shredding them like flimsy pet store toys.

If a lynx is enticed into a trap, the door falls and the animal is left to gnaw the bunny bait, chew the snow packed in the corners and contemplate its folly until the scientists arrive. The lynx is then injected with a sedative from a needle attached to a pole, wrapped in a sleeping bag with plenty of Hot Hands (packets of chemicals that heat up when exposed to the air), pricked for a blood sample that will yield DNA, weighed and measured and, most important, collared with a GPS device and VHF radio transmitter that will record its location every half-hour. “We let the lynx tell us where they go,” Squires says. They’ve trapped 140 animals over the years—84 males and 56 females, which are shrewder and harder to capture yet more essential to the project, because they lead the scientists to springtime dens.

As we career up Elevation Mountain, Squires nods at signs in the snow: grouse tracks, footprints of hares. He stops when he comes to a long cat track.

“Mountain lion,” he says after a moment. It’s only the second time he’s seen the lynx’s great enemy this high up in late winter. But the weather has been warm and the snow is only half its usual depth, allowing the lions to infiltrate. “That’s a bad deal for the lynx,” he says.

The lynx themselves are nowhere to be found. Trap after trap is empty, the bait nibbled by weasels too light to trip the mechanism. Deer fur from old bait is scattered like gray confetti on the ground.

Finally, in the last trap in the series, something stirs—we can see it from the trail. Megan Kosterman and Scott Eggeman, technicians on the project, trudge off to investigate, and Kosterman flashes a triumphant thumbs up. But then she returns with bad news. “It’s just M-120,” she says, disgusted. M-120—beefy, audacious and apparently smart enough to spot a free lunch—is perhaps the world’s least elusive lynx: the scientists catch him several times a year.

Because this glutton was probably the only lynx I’d ever get to see, however, I waded into the woods.

The creature hunched in a far corner of the cage was more yeti than cat, with a thick beard and ears tufted into savage points. His gray face, frosted with white fur, was the very countenance of winter. He paced on gangly legs, making throaty noises like a goat’s nickering, broth-yellow eyes full of loathing.

As we approached, he began hurling himself against the mesh door. “Yup, he knows the drill,” Squires said, yanking it open. The lynx flashed past, his fuzzy rear vanishing into the trees, though he did pause to throw one gloating look over his shoulder.

The lynx team hopped back up on the snowmobiles for another tailbone-busting ride: they were off to a new trapline on the next mountain range over, and there was no time to waste. Squires ends the field research every year in mid- to late March, around when grizzlies usually wake up, hungry for an elk calf or other protein feast. Before long the huckleberries would be out, Cassin’s finches and dark-eyed juncos would sing in the trees, glacier lilies would cover the avalanche slopes. Lately, summer has been coming to the mountains earlier than ever.

Squires, who has blue eyes, a whittled-down woodsman’s frame and a gliding stride that doesn’t slow as a hill steepens, had never seen a lynx before starting his study in 1997. Prior to joining the Forest Service he had been a raptor specialist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Once, when he was holding a golden eagle he’d caught in a trap, its talon seized Squires by the collar of his denim jacket, close to his jugular vein. A few inches more and Squires would have expired alone in the Wyoming sagebrush. He relates this story with a boyish trilling laugh.

Like raptors, lynx also can fly, or so it has sometimes seemed to Squires. During hunts the cats leap so far that trackers have to look hard to spot where they land. Squires has watched a lynx at the top of one tree sail into the branches of another “like a flying squirrel, like Superman—perfect form.”

Lynx weigh about 30 pounds, a bit more than an overfed house cat, but their paws are the size of a mountain lion’s, functioning like snowshoes. They inhabit forest where the snow reaches up to the pine boughs, creating dense cover. They spend hours at a time resting in the snow, creating ice-encrusted depressions called daybeds, where they digest meals or scan for fresh prey. When hares are scarce, lynx also eat deer as well as red squirrels, though such small animals often hide or hibernate beneath the snowpack in winter. Hares—whose feet are as outsize as the lynx’s—are among the few on the surface.

Sometimes lynx leap into tree wells, depressions at the base of trees where little snow accumulates, hoping to flush a hare. Chases are usually over in a few bounds: the lynx’s feet spread even wider when the cat accelerates, letting it push harder off the snow. The cat may cuff the hare before delivering the fatal bite to the head or neck. Often only the intestines and a pair of long white ears remain.

Lynx used to be more widespread in the United States than they are today—nearly half of the states have historical records of them, though some of those animals could have been just passing through. There have been population spikes in the recent past—the 1970s brought a veritable lynx bonanza to Montana and Wyoming, possibly thanks to an overflow of lynx from Canada—but heavy fur trapping likely reduced those numbers. Plus, the habitat that lynx prefer has become fragmented from fires, insect invasions and logging. In 2000, lynx were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Squires began his project in anticipation of the listing, which freed up federal funding for lynx research. At the time, scientists knew almost nothing about the U.S. populations. Montana was thought to be home to about 3,000 animals, but it has become clear that the number is closer to 300. “The stronghold is not a stronghold,” Squires says. “They are much rarer than we thought.” Hundreds more are scattered across Wyoming, Washington, Minnesota and Maine. Wildlife biologists have reintroduced lynx in Colorado, but another reintroduction effort in New York’s Adirondack Mountains fizzled; the animals just could not seem to get a foothold. Bobcats and mountain lions—culinary opportunists not overly dependent on a single prey species—are much more common in the lower 48.

In the vast northern boreal forests, lynx are relatively numerous; the population is densest in Alberta, British Columbia and the Yukon, and there are plenty in Alaska. Those lynx are among the most fecund cats in the world, able to double their numbers in a year if conditions are good. Adult females, which have an average life expectancy of 6 to 10 years (the upper limit is 16), can produce two to five kittens per spring. Many yearlings are able to bear offspring, and kitten survival rates are high.

The northern lynx population rises and falls according to the snowshoe hare’s boom-and-bust cycle. The hare population grows dramatically when there is plenty of vegetation, then crashes as the food thins out and predators (goshawks, bears, fox, coyotes and other animals besides lynx) become superabundant. The cycle repeats every ten years or so. The other predators can move on to different prey, but of course the lynx, the naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton wrote in 1911, “lives on Rabbits, follows the Rabbits, thinks Rabbits, tastes like Rabbits, increases with them, and on their failure dies of starvation in the unrabbited woods.” Science has borne him out. One study in a remote area of Canada showed that during the peak of the hare cycle, there were 30 lynx per every 40 square miles; at the low point, just three lynx survived.

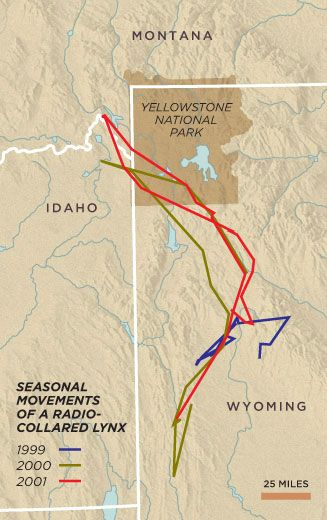

The southern lynx and hare populations, though small, don’t fluctuate as much as those in the north. Because the forests are naturally patchier, the timber harvest is heavier and other predators are more common, hares tend to die off before reaching boom levels. In Montana, the cats are always just eking out a living, with much lower fertility rates. They prowl for hares across huge home ranges of 60 square miles or more (roughly double the typical range size in Canada when the living is easy) and occasionally wander far beyond their own territories, possibly in search of food or mates. Squires kept tabs on one magnificent male that traveled more than 450 miles in the summer of 2001, from the Wyoming Range, south of Jackson, over to West Yellowstone, Montana, and then back again. “Try to appreciate all the challenges that animal confronted in that huge walkabout. Highways, rivers, huge areas,” Squires says. The male starved to death that winter.

Of the animals that died while Squires was tracking them, about a third perished from human-related causes, such as poaching or vehicle collisions; another third were killed by other animals (mostly mountain lions); and the rest starved.

The lynx’s future depends in part on the climate. A recent analysis of 100 years of data showed that Montana now has fewer frigid days and three times as many scorching ones, and the cold weather ends weeks earlier, while the hot weather begins sooner. The trend is likely the result of human-induced climate change, and the mountains are expected to continue heating up as more greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere. This climate shift could devastate lynx and their favorite prey. To blend in with the ground cover, the hare’s coat changes from brown in summer to snowy white in early winter, a camouflage switch that (in Montana) typically happens in October, as daylight grows dramatically shorter. But hares are now sometimes white against a snowless brown background, possibly making them targets for other predators and leaving fewer for lynx, one of the most specialized carnivores. “Specialization has led to success for them,” says L. Scott Mills, a University of Montana wildlife biologist who studies hares. “But might that specialization become a trap as conditions change?”

The lynx’s precarious status makes even slight climate changes worrisome. “It’s surprising to me how consistently low their productivity is over time and how they persist,” Squires says. “They’re living right on the edge.”

To follow the cats into the folds of the Rockies, Squires employs a research team of former trappers and the hardiest grad students—men and women who don’t mind camping in snow, harvesting roadkill for bait, hauling supply sleds on cross-country skis and snowshoeing through valleys where the voices of wolves reverberate.

In the early days of the study, the scientists retrieved the data-packed GPS collars by treeing lynx with hounds; after a chase across hills and ravines, a luckless technician would don climbing spurs and safety ropes, scale a neighboring tree and shoot a sedation dart at the lynx, a firefighter’s net spread below in case the cat tumbled out. (There was no net for the researcher.) Now that the collars are programmed to fall off automatically every August, the most “aerobic” (Squires’ euphemism for backbreaking) aspect of the research is hunting for kittens in the spring. Thrillingly pretty, with eyes blue as the big Montana sky, the kittens are practically impossible to locate in the deep woods, even with the aid of tracking devices attached to their mothers. But the litters must be found, because they indicate the population’s overall health.

Squires’ research has shown time and again how particular lynx are. “Cats are picky and this cat’s pickier than most,” Squires said. They tend to stick to older stands of forest in the winter and venture to younger areas in the summer. In Montana, they almost exclusively colonize portions of woods dominated by Engelmann spruce, with its peeling, fish-scale bark, and sub-alpine fir. They avoid forest that has recently been logged or burned.

Such data are instrumental for forest managers, highway planners and everyone else obligated by the Endangered Species Act to protect lynx habitat. The findings have also helped inform the Nature Conservancy’s recent efforts to buy 310,000 acres of Montana mountains, including one of Squires’ longtime study areas, from a timber company, one of the biggest conservation deals in the country’s history. “I knew there were lynx but didn’t appreciate until I started working with John [Squires] the particular importance of these parcels of land for lynx,” says Maria Mantas, the Conservancy’s western Montana director of science.

Squires’ goal is to map the lynx’s entire range in the state, combining GPS data from collared cats in the remotest areas with aerial photography and satellite images to identify prime habitat. Using computer models of how climate change is progressing, Squires will predict how the lynx’s forest will change and identify the best management strategies to protect it.

The day after our run-in with M-120, the technicians and I drove west three hours across the shortgrass prairie, parallel to the front of the Rockies, to set traps in a rugged unstudied zone along the Teton River, in Lewis and Clark National Forest. The foothills were zigzagged with the trails of bighorn sheep, the high peaks plumed with blowing snow. Gray rock faces grimaced down at us. The vastness of the area and the cunning of our quarry made the task at hand seem suddenly impossible.

The grizzlies were “probably” still slumbering, we were assured at the ranger station, but there wasn’t much snow on the ground. We unhitched the snowmobiles from their trailers and eased the machines over melting roads toward a drafty cabin where we spent the night.

The next morning, Eggeman and Kosterman zoomed off on their snowmobiles to set the traps in hidden spots off the trail, twisting wire with chapped hands to secure the bait, dangling CDs and filing the trap doors so they fell smoothly. The surrounding snow was full of saucer-size lynx tracks.

On our way out of the park, we were flagged down by a man on the side of the road wearing a purple bandanna and a flannel vest.

“Whatchya doing up there?” he asked, his eyes sliding over the research truck. “See any lions? Wolverines?” He waggled his eyebrows significantly. “Lynx?”

Kosterman didn’t answer.

“I take my dogs here to run cats sometimes,” he confided. Chasing mountain lions is a pastime for some local outdoorsmen, and the dogs can’t typically distinguish between lions—which are legal to hunt and, during certain seasons, kill—and the protected lynx, many of which have been shot over the years, either by accident or on purpose.The scientists worry about what would happen if an unscrupulous hunter stumbled on a trapped lynx.

The man in flannel continued to question Kosterman, who said little and regarded him with quiet eyes. There’s no point in learning a lynx’s secrets if you can’t keep them.

Back in the garnets the next morning, Squires was delighted: snow had fallen overnight, and the mountains felt muffled and snug.

His good mood didn’t last long. When we set out to check the trapline, he saw that a lynx had paced around one trap and then thought better of entering despite the bunny lashed to the side. The cat was a coveted female, judging from the small size of the retreating tracks.

“What a drag,” Squires said. “She checked it out and said, ‘Nope.’ Flat-out rejected it!” He sounded like a jilted bridegroom. He turned to the technicians with uncharacteristic sternness: “The hare’s all wadded up—stretch it out so it looks like a hare! We need feathers in that trap. Wings!”

Later that day, we drove back hundreds of miles to check the newly set traps in the Lewis and Clark National Forest.

They were empty.

By lantern light in the cabin that night, Squires talked of shutting down the new trapline. There were too many miles to cover between the Garnet and Lewis and Clark sites, he said. It was too much work for a small crew.

In the morning, though, the air was fresh and chilly. The mud-encrusted truck was covered with smudges where deer had licked off road salt in the night. New snow lay smooth as rolled dough, with lynx prints as neat as if stamped with a cookie cutter.

Squires was reborn. “Oh, I’d like to trap that cat!” he cried for what must have been the thousandth time that season, blue eyes blazing.

The traplines stayed open.

Staff writer Abigail Tucker last wrote about the artist Arcimboldo. Ted Wood is a nature photographer in Boulder, Colorado.