Trailblazing Engineer Irene Peden Broke Antarctic Barriers for Women

Originally told she could not go to Antarctica without another woman to accompany her, Peden now has a line of cliffs on the continent named in her honor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/ee/74ee8780-8797-4ee3-8c1f-9abc52c3721e/screen-shot-2019-06-03-at-53406-pm.jpg)

Irene Peden needed to get on the plane for Christchurch, New Zealand, or it was going to leave without her. But before she could continue on from New Zealand to the bottom of the world, where she planned to conduct research on the properties of Antarctic ice, someone needed to find another woman—and fast.

In 1970, Peden was en route to become the first female principal investigator working in the Antarctic interior. But the Navy, which oversaw Antarctic logistics at the time, would not let her go unless another woman accompanied her. The New Zealand geophysicist originally scheduled to join Peden was disqualified at the last minute after failing to pass her physical. Peden got on the plane to New Zealand not knowing whether she would be able to continue on to Antarctica or if her project was doomed to fail before it even began.

By the time her plane touched down in Christchurch, a new companion had been arranged. A local librarian named Julia Vickers would join Peden in Antarctica as her field assistant. Vickers wasn’t a scientist, she was a member of a New Zealand alpine club, but scientific skills weren’t a requirement for the trip. Vickers just had to be female and pass her physical exam, which was no problem for the experienced mountaineer.

The requirement to bring another woman along was just one of the many roadblocks Peden faced on her way to Antarctica, where she planned to use radio waves to probe the continent’s ice sheets. She recalls the Navy saying they needed another woman present for any medical treatment Peden may require during her time on the continent. “The only thing I figured that was [going to] happen was that I’d turn an ankle, and what darn difference would it make?” recalls Peden, now 93 years old and living in Seattle.

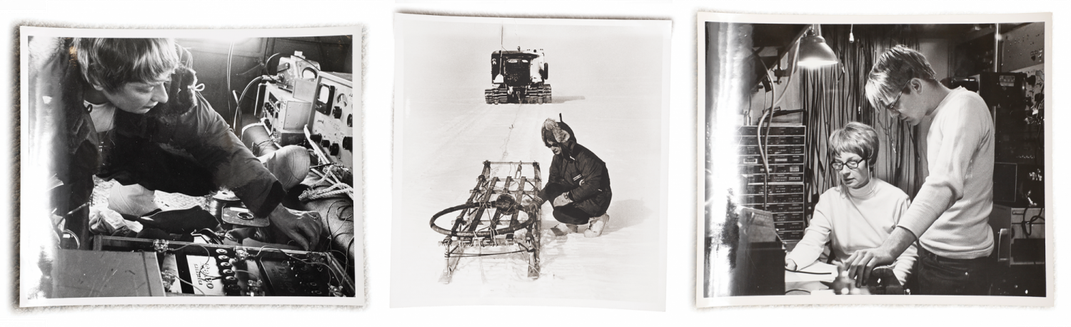

Peden didn’t require medical treatment during her month-long stay in the Antarctic interior, but she did face a host of challenges. When she arrived, it was so cold and dry that her glasses snapped in half, saved by a fortuitous bottle of epoxy. Her nails broke off and she suffered constant nosebleeds and headaches, but despite the brutal environment, she got right to work. Her research involved deploying a probe deep into the ice sheet to study how very low frequency (VLF) radio waves travel through the ice.

The year before Peden’s arrival, Christine Muller-Schwarze studied penguins with her husband on Ross Island, becoming the first woman to conduct research in Antarctica, and a group of six women reached the geographic South Pole in November 1969. Peden, however, became the first woman to conduct her own research in Antarctica’s interior—one of the harshest environments on Earth.

Previously, scientists would collect surface ice measurements and infer the properties of subsurface realms, but Peden had a plan to delve into the research even further. Her team was the first to measure many of the electrical properties of the Antarctic ice sheets and determine how VLF radio waves propagate over long polar distances. The work was later expanded to measure the thickness of the ice sheets and search for structures underneath the surface using a variety of radio wave frequencies.

Near Byrd Station, the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research Laboratories had drilled a 2.16-kilometer-deep hole in the ice in 1967, and Peden used the hole to lower her probe. The hole originally went to the bottom of the ice sheet, and it still reached 1.67 kilometers into the icy depths when Peden arrived in 1970. The probe included two capsules of electronic equipment, including telemetry instruments, a receiver, data amplifier and signal amplifier.

Crucial pieces of gear were lost in transit, so Peden borrowed and modified equipment from a Stanford graduate student. She and Vickers worked 12-hour days in temperatures that dipped to minus 50 degrees Celsius, enduring whiteout blizzards and gusting winds.

A lot was riding on Peden’s work beyond developing a new tool to probe the icy subsurface of Antarctica. Although the National Science Foundation (NSF) was supportive of Peden’s work, the Navy was still hesitant to bring women to the southern continent. Peden was unofficially told before she departed that if she did not complete her experiment and publish the results, another woman wouldn’t be allowed to follow in her footsteps for at least a generation.

“If my experiment was not successful, they were never going to take another woman to the Antarctic,” Peden says. “That’s what [the Navy] told [NSF], and that’s what NSF told me. So they put a lot of pressure on me through NSF—‘you must not fail.’ Well, that’s a difficult thing to tell a person doing experimental work, because if it’s experimental and it’s really research, you don’t know how it’s going to turn out until it does. So that was a bit of a risk, but I was quite willing to take it. I thought I knew what I was doing.”

Peden’s experiment was a success, and she was able to describe how the radio waves propagated through the ice in a published study. Her achievements were so significant that Peden Cliffs in Antarctica were later named in her honor, though she’s never seen them in person.

Peden’s career accomplishments are multifold despite facing numerous obstacles due to her sex. She graduated from the University of Colorado—where she was often the only woman in her classes—with a degree in electrical engineering in 1947. Then she earned a master’s degree and the first PhD in electrical engineering awarded to a woman from Stanford University. In 1962, she became the first woman to join the University of Washington’s College of Engineering faculty, and she served as president of the IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society, receiving the organization’s “Man of the Year” award. She was the National Science Foundation’s Engineer of the Year in 1993, and her achievements earned her a spot in the American Society for Engineering Education’s Hall of Fame.

Growing up, Peden’s greatest inspiration was her mother, whose father didn’t believe in education for women. Peden’s mother and aunt both wanted to go to college, so they took turns working and putting each other through school. Though her mother wasn’t able to complete her degree, both sisters achieved their goal of attaining teaching jobs in western Kansas.

When she was the only woman in her classes, Peden didn’t let it bother her. “I never felt uncomfortable about it,” she says. “Sure, they made me feel like I was an outsider and I was aware of all that, but I wasn’t as troubled by it as I think some girls would have been because I had that picture deep in my heart that mother had done it, so it must have been alright.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/1d/0e1de58e-69c0-4687-a929-fc5cbff81dc9/peden84.png)

Since Peden completed her schooling and research trip to Antarctica, the landscape of science research has progressed. The director of the NSF Office of Polar Programs and the U.S. Antarctic program is a woman: Kelly Falkner. An oceanographer by trade, she has also faced obstacles due to her sex during her career, including a period in the 1980s and into the 1990s when she wasn’t allowed on Navy submarines to conduct research. She highlights issues of sexual harassment in remote field environments, such as Antarctica.

“You never know where the best ideas are going to come from in science, and so if you start to close the doors either directly or indirectly, like for example by harassment, then you really cut off a talent pool for moving the field forward,” Falkner says. “I think that’s pretty fundamental to diversity in general, and certainly women are a strong part of making sure that we’re getting the full talent pool at the table.”

Thanks to trailblazing pioneers like Peden, women are able to come to the table, or the Antarctic interior, to make critical contributions to scientific research all around the globe.