Trapped as Climate Changes, Giant Gusts of Hot Air Trigger Weather Extremes

Thanks to global warming, hot air piles up at mid-latitudes and causes storms and heat waves to linger for long stretches of time, new research shows.

![]()

Scientists have identified a link between global warming and extreme weather events such as heat waves. Photo by Flickr user perfectsnap

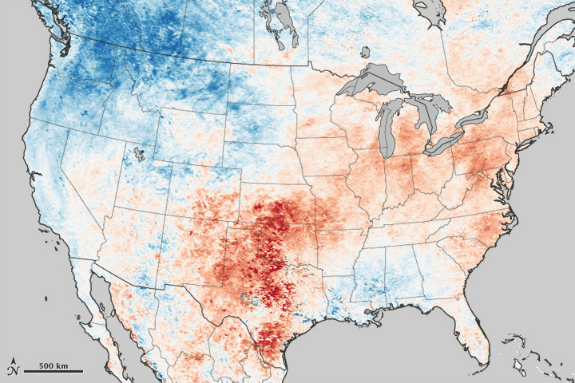

During the month of July 2011, the United States was seized by a heat wave so severe that roughly 9,000 temperature records were set, 64 people were killed and a total of 200 million Americans were left very sweaty. Temperatures hit 117 degrees Fahrenheit in Shamrock, Texas, and residents of Dallas spent 34 consecutive days stewing in 100-plus-degree weather.

For the past couple of years, we’ve heard that extreme weather like this is tied to climate change, but until now, scientists weren’t sure exactly how the two were related. A new study published yesterday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals the mechanism behind events such as the 2011 heat wave.

What it comes down to, according to scientists at Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), is that higher temperatures caused by global warming are disrupting the flow of planetary waves that oscillate between Arctic and tropical regions, redistributing the warm and cold air that usually help regulate the Earth’s climate. “When they swing up, these waves suck warm air from the tropics to Europe, Russia, or the US, and when they swing down, they do the same thing with cold air from the Arctic,” lead author Vladimir Petoukhov of PIK explained in a statement.

Under pre-global-warming conditions, the waves might have initiated a short, two-day burst of warm air followed by a rush of cooler air in Northern Europe, for example. But these days, with global temperatures having climbed 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit in the past century and escalating particularly sharply since the 1970s, the waves increasingly stall out, resulting in 20- to 30-day heat waves.

The way it occurs is this: The greater the temperature difference between regions like the Arctic and Northern Europe, the more air circulates between the areas–warm air rises over Europe, cools over the Arctic, and rushes back down to Europe, keeping it chilly. But with global warming heating up the Arctic, the temperature gap between the regions is closing, stanching the flow of air. In addition, land masses warm and cool more easily than oceans. ”These two factors are crucial for the mechanism we detected,” Petoukhov said. “They result in an unnatural pattern of the mid-latitude air flow, so that for extended periods the… waves get trapped.”

The scientists developed models of this phenomenon and then entered daily weather data for the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere during the summers from 1980 to 2012. They found that during several major heat waves and episodes of prolonged rain–which led to floods–the planetary waves had indeed been trapped and amplified.

Researchers examined the July 2011 heat wave in the U.S. for new clues on global warming and extreme weather. (Reds represent above-average temperatures and blues are lower-than-average temps.) Image via NASA Earth Observatory

“Our dynamical analysis helps to explain the increasing number of novel weather extremes,” said Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, director of PIK and co-author of the study. “It complements previous research that already linked such phenomena to climate change, but did not yet identify a mechanism behind it.”

The research joins another recent study (PDF) by scientists at Harvard that highlights how changes to air circulation patterns are spreading drought. As warm tropical air rises, it triggers rains before migrating to higher latitudes. The dry air then descends, heats up and eventually travels again, landing in regions characterized by desert. These dry regions used to be confined to narrow bands spanning the globe. But now, these bands are expanding by several degrees in latitude.

“That’s a big deal, because if you shift where deserts are by just a few degrees, you’re talking about moving the southwestern desert into the grain-producing region of the country, or moving the Sahara into southern Europe,” study author Michael McElroy said in a statement. In this way, climate change threatens national security because drought, heat and other extreme weather events can jeopardize food stocks, destroy roads and bridges, and ultimately lead to political instability, the authors note.

The connection between climate change and extreme weather will be highlighted this summer, if current trends continue. The summer of 2012 was even hotter in the U.S. than that of 2011, and according to the PIK scientists, it was also marked by prolonged, amplified waves in the mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

Unfortunately, the frequency of these atmospheric patterns is only expected to increase. When the researchers compared the period from 1980 to 1990 with that from 2002 to 2012, they saw that the incidence of trapped waves had doubled. Bottom line: Heat waves are not only here to stay, they’ll become more frequent and will linger for longer.