The True Inner Beauty of Fishes

A biologist and a poet team up for a new exhibition at the Seattle Aquarium that features images of bleached and stained fish skeletons

The skills that make a good biologist are not unlike those that make a good artist. “A desire to understand detail, you focus on how things work. These things are qualities that good poets and good biologists share,” says Adam Summers, a biologist at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Labs and consultant on Finding Nemo.

Summers draws on his talents as a biologist and a photographer for “Cleared: the Art of Science,”an exhibition now at the Seattle Aquarium. The show depicts fish specimens, bleached and stained to reveal the complex skeletal structures beneath their scales.

Fish fascinated Summers, even as a graduate student. “Always what interested me was the interplay of physics and engineering with structure and evolution. So, when I saw in museum collections, these cleared and stained animals. I was immediately taken with them,” he says.

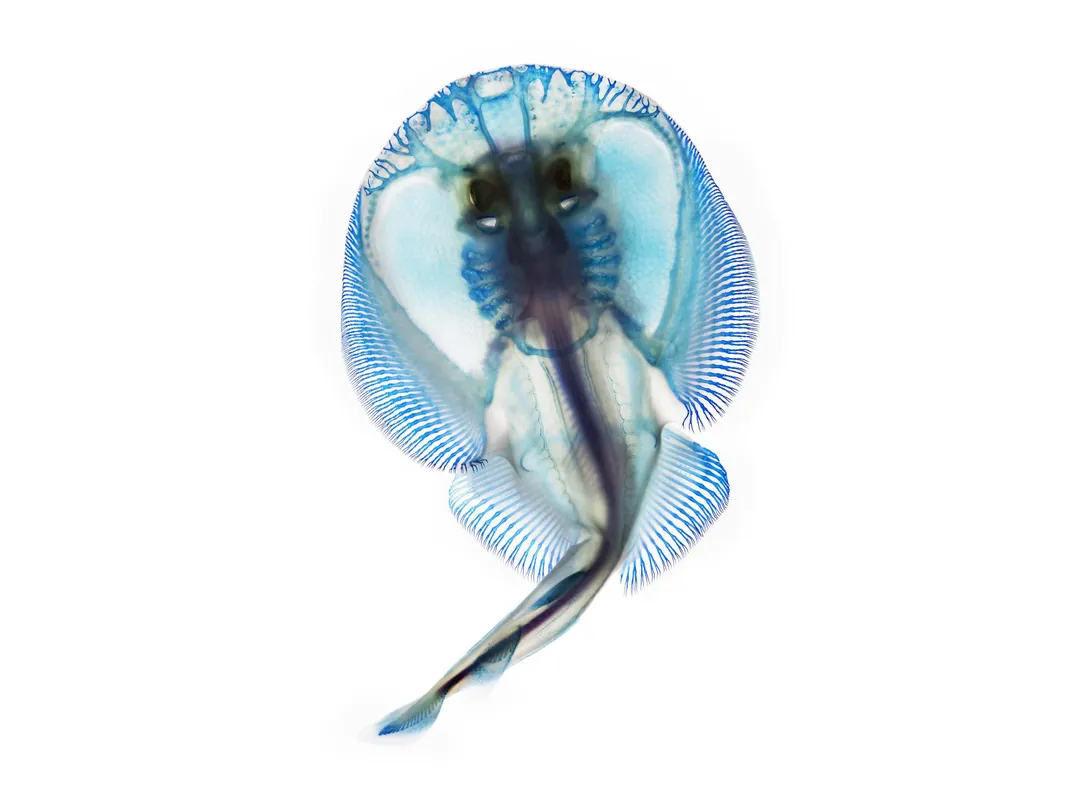

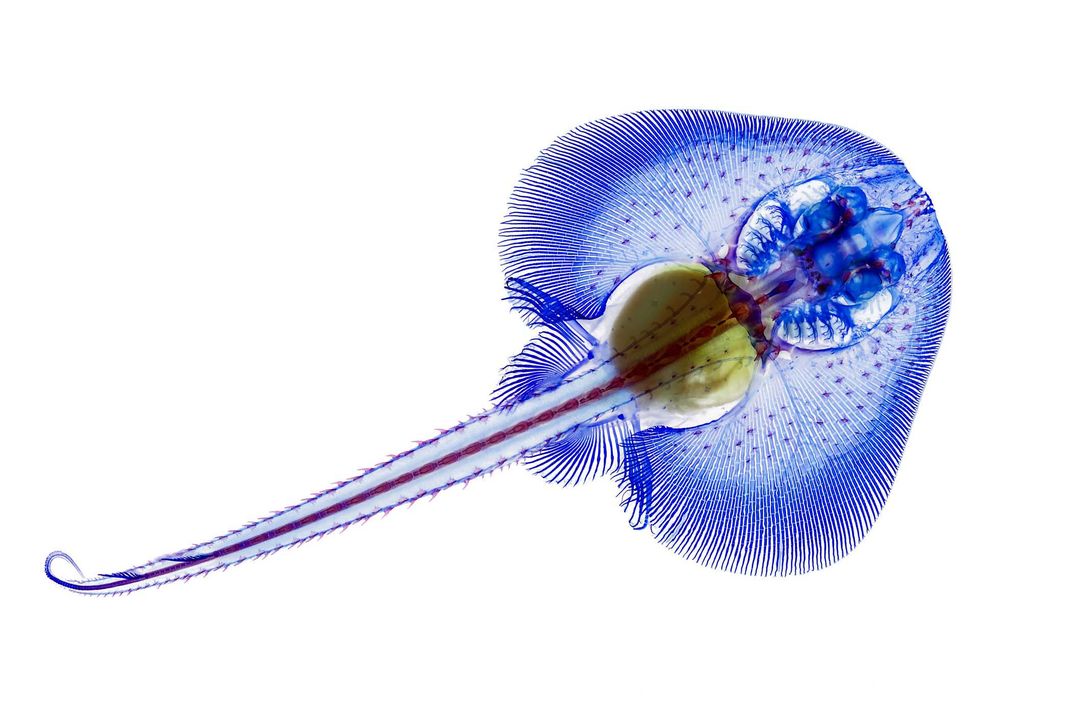

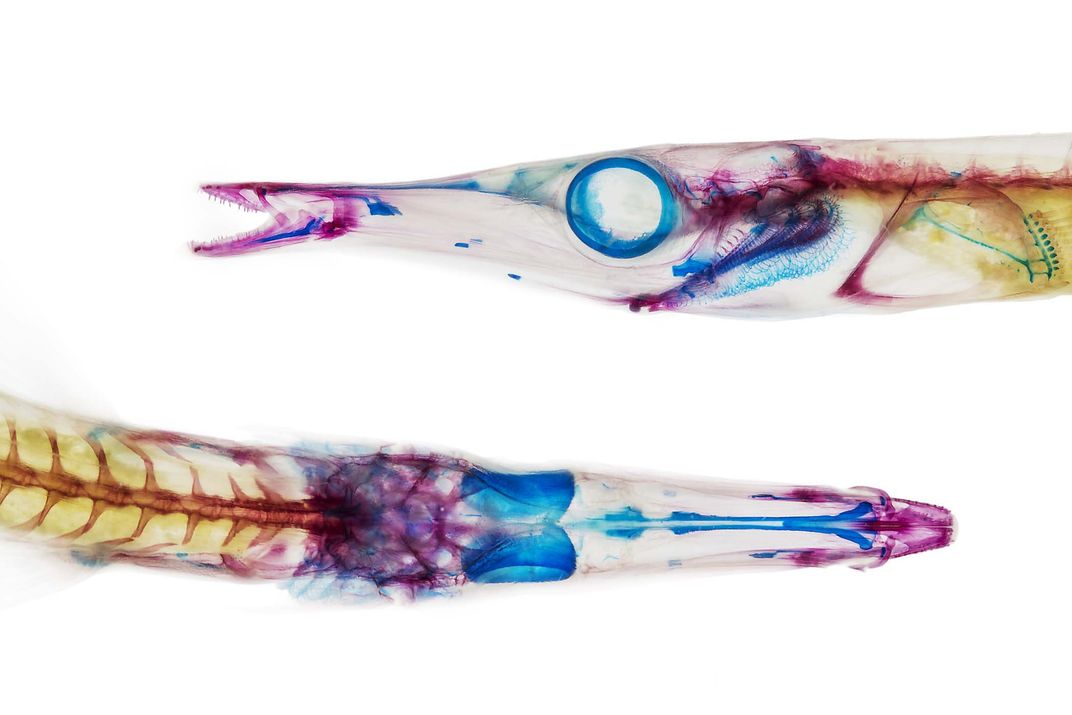

"Cleared" fish are fish rendered translucent by a combination treatment: hydrogen peroxide to dissolve dark pigments, a digestive enzyme called trypsin to dissolve the flesh apart from collagen in the fish's skin and skeleton and glycerin to make skin and connective issue appear invisible. The technique Summers uses to clear and stain fish has been common practice of reasearchers for decades and relies on two dies: Alcian blue, which gives cartilage a blue hue, and Alizarin Red S, a red dye that acts on bone. Summers made a habit of including an image in the scientific papers he would submit to different journals; the image, directly related to the research at hand, was often selected as the publication's cover art.

Some of the specimens featured in the exhibition came from bycatch and others were part of a study examining how fish skeletons develop. Once a fish specimen enters Summers’ lab, it might end up in several different studies on fish skeletal structures, how they work and why they’re important. Photographs of the wings of a butterfly ray and skate species, for instance, provided insight into how a wing fin propels the fish forward, a finding with applications in robotics. More recently, the lab used a cleared and stained image of a northern clingfish to figure out how the fish’s belly sucker, which can adhere to any surface, works.

Summers' first images were more scientifically oriented than artistic, so when the opportunity arose to put together an exhibition for the aquarium, he took new shots of many of the fish, trying to achieve a more aesthetic affect. “I now sort of understand that in order to make the animal relate to you, you need to have some action and motion, some asymmetry, and a sense of movement is really helpful,” he says.

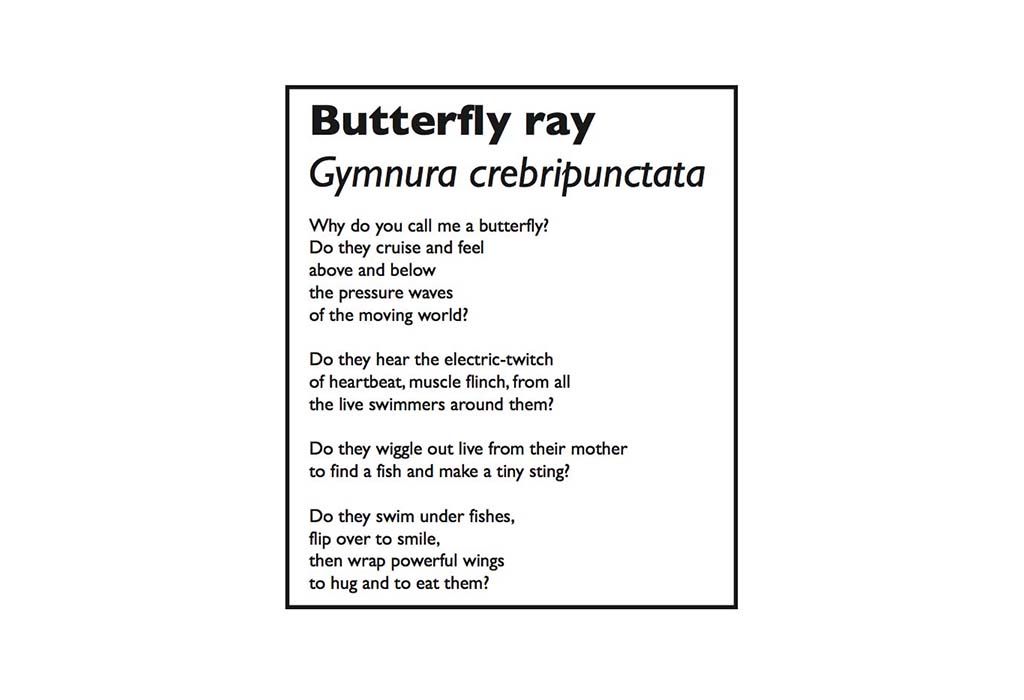

The idea of standard captions for the images also seemed underwhelming to Summers. So, he asked Sierra Nelson, a poet based in Seattle, if she would be interested in writing a poem to go with each fish. Nelson and Summers had worked together on another art-meets-science endeavor: teaching companion courses on poetry and marine biology in a special program at Friday Harbor Labs. For the cleared and stained specimens, having a caption as a poem “actually tells a lot about the actual biology of the fish,” he says. “That’s the way Sierra works in her poetry.”

The experience has been enriching for Summers, who says that he's learned more about art and how to communicate with the general public. Because the lab’s research is largely funded by the National Science Foundation, he feels it’s important for taxpayers to see what they’re paying for. “I hope that people looking at it get some appreciation for the internal beauty of fishes. That there’s more to them than swimming around in an aquarium,” he says. “There really is this other dimension of their biology that’s worth appreciating.”

"Cleared" will be at the Seattle Aquarium through March, and Summers plans to take the exhibition to Northern California in 2014 and New Zealand in 2015.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)