Tunnel Vision

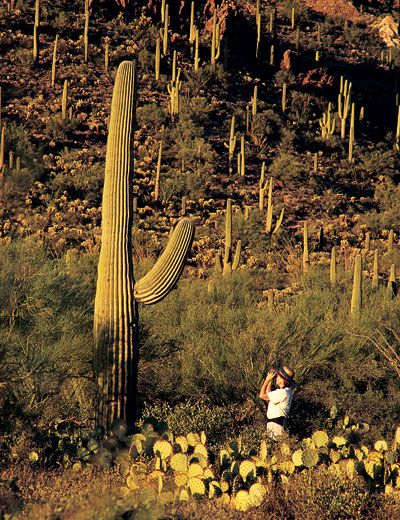

Arizona Naturalist Pinau Merlin celebrates life in the desert by keeping a close eye on it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/tunnel2_353_388.jpg)

Pinau Merlin likes to watch things. She especially likes to watch holes in the ground. Big holes, little holes. Ant holes, perhaps, or pack rat holes, badger holes, bumblebee holes. Mysterious holes for which there are no obvious reasons or explanations.

Recently, author T. Edward Nickens followed Merlin all over Arizona's Rincon Mountains in search of holes to watch. After three days his eyeballs were exhausted. Nickens and Merlin eagerly waited, and watched, outside a female tarantula's burrow—to no avail—for the spider to make an appearance. They watched Gila monsters drinking from small pools high in the Rincons. They watched great horned owl chicks staring amber-eyed from their roosts. They watched ants, bees, wasps, lizards, ground squirrels, cactus wrens, caracaras and assorted snakes dive into, peer out of, attack prey and copulate in various holes, dens, burrows and depressions.

"The more you know about what you see, the more you come to appreciate the intricacies of life, and the fantastic ways that animals have evolved to live in specific environments," Merlin says. "And looking at holes is a great way to get to know the neighbors. You see rabbit fur by the kit fox hole, and it's like reading the morning paper. Who was out last night? What were they doing?"

Some people might consider the act of watching holes in the ground an unfruitful enterprise, but more than 6,000 enthusiasts have bought Merlin's Field Guide to Desert Holes. Published two years ago by the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, just outside Tucson, it's now in its second printing and is being distributed nationally.

"There is this sense of having to be productive, having to justify your every moment," Merlin says. "When I take people out to the desert now, I have them just sit, and listen, and sniff, and look." She cocks an ear toward the sound of a tree frog "bleating" up-canyon. "Usually five minutes is enough."