The Ultimate Summer Camp Activity: Digging for Dinosaurs

Meet the intrepid teenagers and teenagers-at-heart who swelter in the heat hunting for fossils

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/17/bf175fcd-5379-46c3-83e6-41c9fc7d9c71/img_1832.jpg)

The bone digger is unloading his truck when three of his teen volunteers come loping toward him, flush with excitement.

“I think we found a theropod hand!” says Isiah Newbins.

The then-rising senior from Cherokee Trails High School in Aurora, Colorado, is dripping sweat; his clothes are muddied with the slippery, volcanic clay known hereabouts as gumbo. His face is alight with the glow of discovery—equal parts scientific interest and little-boy hope.

It’s been a long day in the Hell Creek Formation, a 300-foot-thick bed of sandstone and mudstone that dates back to a period between 65 and 67.5 million years ago, to a time before dinosaurs became extinct. Stretching across the Dakotas and Montana (in Wyoming, it’s known as the Lance Formation), Hell Creek is one of the richest fossil troves in the world, left behind by great rivers that once flowed eastward toward an inland sea.

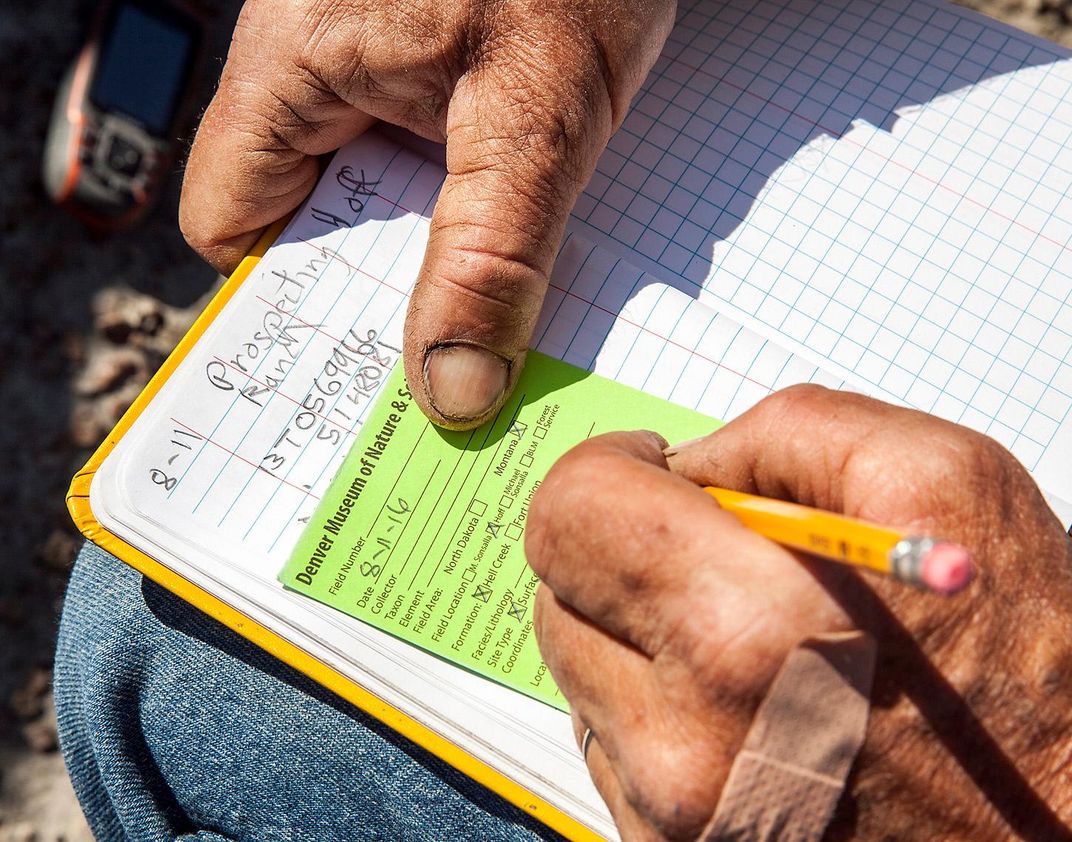

It’s August 2016, and Newbins has been hunting fossils in the heat with a team from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Every summer the DMNS, in cooperation with the Marmarth Research Foundation, offers several weeks of programs and research opportunities for students, academics, and serious hobbyists. A sort of ultimate fantasy camp for would-be paleontologists, the age among the 35 attendees and staff this week ranges from 15 to 80.

Theropods were carnivorous dinosaurs, bipedal predators like the T. rex—perhaps the most fearsome and captivating of all the extinct species, at least to the general public. To Newbins, who’ll be applying this fall to undergraduate paleontology programs, finding the possible hand is “unbelievably surreal—kind of like a dream-come-true moment.” As he will later say, echoing the sentiments of most in attendance at the gathering: “You know how everybody likes dinosaurs when they’re kids? I never stopped.”

The bone digger thumbs back the brim of his well-seasoned Aussie bush hat. “Theropods are rare,” says Tyler Lyson, 34. He’s been prospecting these parts for fossils since he was young. He raises his eyebrows skeptically. “I mean, very rare.”

Lyson is the founder of the MRF; he is employed as a curator with the Denver Museum. A Yale-trained paleontologist with a specialty in fossil vertebrates—more specifically dinosaurs and turtles—Lyson (pronounced Lee-sun) was born and raised here in Marmarth, population 143, a once-thriving railroad town in the far southwest corner of North Dakota.

The Lonely Hedonist: True Stories of Sex, Drugs, Dinosaurs and Peter Dinklage

Best-selling author Mike Sager has been called “the Beat poet of American journalism, that rare reporter who can make literature out of shabby reality.” The Lonely Hedonist: True Stories of Sex, Drugs, Dinosaurs and Peter Dinklage is Sager’s sixth collection of true stories—sixteen intimate profiles of larger-than-life Americans, both famous and obscure

Lyson was just 16—a year younger than Newbins—when he spotted his first serious fossil, a mummified hadrosaur, or duck-billed dinosaur, later nicknamed “Dakota.” An extraordinary find, Dakota had apparently died near the bend of a river, where its body was rapidly buried under accumulating sediment. The wet, mineral-rich environment protected the specimen from decay, leaving a detailed preservation of the dinosaur’s skin, bones and soft tissue. Eventually, the fees Lyson collected for loaning Dakota to a Japanese exposition would help him build out his foundation’s summer program, which he started as a college sophomore with four attendees in 2003. (Dakota later found a permanent home at the North Dakota Heritage Center in Bismarck.)

“Were there multiple bones?” Lyson asks.

Jeremy Wyman, 18, pulls out his cell phone, searches for a photo. “It looked like multiple bones and multiple hand bones,” he says. “But then again—” his voice trails off.

Lyson squints at the photo through his prescription aviator shades. With his scrubby beard and dirty, long sleeve shirt, he looks like a guy who’s just spent the day hiking ten miles though the thorny, sage-scented territory in the 90 degree heat.

“Ian said he thought it might be a hand,” says Newbins, pleading his case. Ian is Ian Miller, their chaperone in the field today, a specialist in fossil plants who heads the paleontology department at the Denver Museum, making him Lyson’s boss. Miller is visiting this week, as he does annually. Later this evening, after a dinner of Chinese carryout (from restaurant 20 miles away, across the Montana state line) Miller will be giving a lecture about the Snowmastodon Project of 2010, when he helped to lead an effort to harvest an important site that had been found unexpectedly during the re-construction of a reservoir in the resort town of Snowmass, Colorado. During the six-month window they were allowed, the crew unearthed 4,826 bones from 26 different Ice Age vertebrates, including mammoths, mastodons, bisons, American camels, a Pleistocene horse and the first ground sloth ever found in Colorado.

Lyson returns the phone to Wyman. “I kind of wanna go look at it right now,” he says.

“I could go get my field stuff,” Newbins says.

“If that’s a theropod hand,” Lyson says, “I’m gonna give you the biggest hug.”

“I’m gonna give myself a huge hug,” Newbins says.

**********

The bone digger is digging.

Perched on a low shelf of rock at the bottom of a wash, Lyson scrapes gingerly with the three-inch blade of a Swiss Army knife. Now and then he uses a small hand broom to wisk away the dust. He scrapes some more.

The object of his attention is what appears to be a perfectly intact shell of an Axestemys, an extinct soft-shelled turtle that grew to three and a half feet in diameter. A cousin of the large sacred turtles found in various temples in Asia, it was the largest animal in North America to survive the great extinction. You might say turtles were Lyson’s first paleontological love. Over time he has become one of the world’s foremost experts on turtle evolution. His latest work solves the mystery of how the turtle got its shell. Earlier in the day, a couple of dozen volunteers from the MRF walked right past the fossilized shell without seeing it. Then Lyson caught sight of it—a brownish edge sticking out of the weathered ochre slope. Dropping his backpack on the spot, he got right to work.

At 3,000 feet of elevation, the air is slightly thin; the sun’s rays feel harsh against the skin. Prior to 65 million years ago, this part of the arid Badlands was at sea level. A moderately wet area, with lakes and streams, palms and ferns, it resembled the modern Gulf Coast. Today, along with the prickly pear cactus and desert grasses—and the slippery sheets of gumbo collected in low areas like so many ponds of ice (used by oil companies as a lubricant for oil drilling)—the ground is a trove of minerals and fossils, bits and pieces of larger chunks that have weathered out of the sides of the buttes, evidence of the eternal cycle of erosion, and of the treasures buried all around.

The group from the MRF is fanned out along the network of gullies and buttes within shouting distance of Lyson. By summer’s end, more than 100 will have passed through the program, including student teams from Yale University, Brooklyn College and the Smithsonian Institution. This week’s group includes a retired auditor who has traveled to 49 of the 50 states; a retired science teacher credited with the 1997 find of an important T. rex named Peck’s Rex; a 23-year-old whose grandfather employed Lyson, while still a teenager, to recover a triceratops; and the mother of a young grad student who just wanted to see what her daughter’s chosen life is all about. One crew applies a plaster cast to a bone from a pterosaur, a flying reptile, a rare find. Another uses brushes, rock hammers and awls to unearth the jawbone and partial skull of a champsasaur, an alligator-like animal with a thin snout. Up on top of a nearby butte, a third crew attends to a rich vein of fossil leaves.

Another crew is equipped with a portable GPS system. Over the past two years, Lyson and his collaborators have hiked hundreds of miles in an attempt to create a computerized map of the K/T Boundary. Known more formally as the Cretaceous–Tertiary Boundary (the German word kreide, meaning chalk, is the traditional abbreviation for the Cretaceous Period), the K/T Boundary is an iridium-rich sedimentary layer that scientists believe marks in geologic time the catastrophic event—an asteroid colliding with the earth—that led to the extinction of the dinosaurs and much of the earth’s fauna, paving the way for the evolution of mammals and modern plants.

By placing all of the readings on a map—and by adding locations where fossils have been found (including samples of leaves and pollen) over a hundred-year period by researchers from the Smithsonian, the Denver Museum, and other regional museums—Lyson and the others have created a three-dimensional image of the boundary that will aid in dating past and future finds. Simply put, if you’re below the boundary, you’re in the Cretaceous, the world of the dinosaurs. If you’re above, you’re in the Paleocene, the world of the mammals. Lyson and the others hope this data will help them more accurately depict the sequence of events of the great extinction. Did it happen all at once? Was it gradual? What was the timing across the globe?

At the moment, Lyson has taken a break from mapping to do something he’s had precious little time for this summer—collecting a fossil. While the abundance of volunteers makes the painstaking tasks of digging and preparing fossils more efficient—everything taken will be donated eventually to public museums—it means that Lyson spends a lot more time administrating . . . and mapping.

We are a few miles outside of Marmarth, founded in the early 1900s as a hub along a railroad line, leading from Chicago to Seattle, that was built to aid in settlement of the great northern plains. The town was named for the railroad owner’s grandaughter, Margaret Martha Finch. Despite a boom in the 1930s, caused by the discovery of oil nearby, the population has continued to dwindle from its high of 5,000. These days, locals say, a large percentage of Marmarth residents are retirees, here for the modest cost of living. There is one bar/restaurant, a classic automobile museum, a coffee-shop/tobacco store, and a former railroad bunkhouse that rents out rooms—during summers it serves as the MRF dorm.

The land where Lyson is digging is owned by his uncle; Lyson’s maternal family, the Sonsallas, have ranched here for three generations. An important factor in fossil hunting is land ownership. Permission is needed to dig on both private and public lands, the latter managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Lyson’s dad, Ranse, hails from a farming family in Montana. After a stint as a nuclear submariner, he worked as a D.J. at a small radio station in Baker, Montana, where he met the former Molly Sonsalla. The couple married and settled in Marmarth; Ranse went to work for the oil company. The couple had three boys. The Hell Creek Formation was their playground.

“My mom would drop us off and we’d run around and chase rabbits and look for fossils and arrowheads,” Lyson says, scratch-scratch-scratching at the sand with his knife. “I was the youngest. My older brothers would constantly beat me up, and I always gave them a run for their money. One of the guys we’d go fishing with, his nickname was Bear—everybody around here has nicknames. And one time he said to me, ‘You’re gonna be tough when you grow up.’ I guess it stuck.”

“Tuffy” Lyson was in fourth or fifth grade when he came across his first important find—a trove of giant turtle shells; he named it the Turtle Graveyard. Likely they had died together as a pond dried up, he hypothesized. The next year he found his first hadrosaur. (Dakota would come later, in high school.) When he’d finished unearthing it, Lyson remembers, he took a piece of the fossil in a shoebox down to the bunkhouse—only three blocks from his parents’ place--where all the commercial prospectors and academics would stay every summer while doing their field work.

“I’d just hang around and I wouldn’t leave until they’d take me out digging. You can imagine how annoying I was. They gave me a hard time but I was pretty resilient,” Lyson says. From the spot where he’s working on the turtle shell, the butte where he found his first hadrosaur is about one mile north. The locals call it Tuffy Butte.

“Look at the size of that thing,” says Kirk Johnson, interrupting Lyson’s story.

Johnson, 56, is a Yale-trained paleobotanist and the director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History. He’s been doing field work in Marmarth since he was an undergrad. He met Lyson when he was about 12, when Lyson was a “little gumbo butte Sherpa,” Johnson says. Lyson affectionately calls him “Dr. J.” Johnson was instrumental in helping to convince Lyson’s parents—who lived in a town where most of the sons went to work for the oil company—that their son could make an actual, paying career in paleontology. Eventually Lyson would go on to scholarships at Swarthmore and Yale.

“He’s that rarest of all rare things, a native paleontologist,” Johnson says of Lyson. “He’s remarkable in the field because he’s trained his eye since he was small. He can see everything.”

“At least 25 people strolled right past it, and then I spotted it,” Lyson says of his turtle shell find, pointing to the distinctive raindrop pattern of the markings on the surface of the shell. His face is alight with the glow of discovery—equal parts scientific interest and little-boy hope.

**********

The bone digger is standing on stage, beside a podium, wearing clean chinos and a button-down oxford shirt

We are 60 miles southwest of Marmarth, in the town of Ekalaka (Eee-ka-laka), Montana. With a population of 300, it’s another close-knit, Badlands ranching community, rich in fossils. The audience is a diverse collection, 200 academics, dinosaur enthusiasts, ranch owners, and community members who have gathered in the pews and folding chairs of the spacious sanctuary at the St. Elizabeth Lutheran Church to celebrate the fourth annual Ekalaka Shindig.

Part small-town fair, part open-door conference, the Shindig is a weekend-long celebration of Ekalaka’s contribution to paleontology, with a lecture program, kids’ activities, field expeditions and live music. Central to the entire program is the Carter County Museum, the first of its kind in Montana, founded in 1936. The museum’s guiding force was a local high school teacher named Marshall Lambert, who died in 2005 at the age of 90. He taught science to some of the old-timers in the crowd—as part of his curriculum, he took his students into the field to collect fossils. Today many of those students are landowners. Their cooperation is key.

The Shindig lectures started at nine this morning. Right now it’s almost noon. As can be expected—besides being hot and dusty, life is a little bit slower out here where some cell phones have no service—things are running a bit late. Standing on the stage next to Lyson, getting ready to introduce him, is another bone digger. His name is Nate Carroll, but everybody calls him Ekalaka Jones.

Carroll is 29 years old with a mop of black hair, wearing his trademark blue denim overalls. As the curator of the museum, the Ekalaka Shindig is his creation.

Like Lyson, Carroll grew up with the Badlands as his playground; his family goes back four generations. At 15, after a T. rex was unearthed 20 minutes away from his family’s ranch, Carroll volunteered to work on the dig, sponsored by the LA County Museum. By his senior year in high school, he’d landed a spot as a paid field assistant. Currently he’s pursuing his Ph.D. at the University of Southern California. As an undergrad he focused on pterosaurs. Lately he’s been more fascinated with amber. The secret to becoming a successful academic is finding a unique area of study—you’re not just out digging bones, you’re trying to figure out a particular piece of history’s puzzle.

In 2012, Carroll decided to find a way to bring together all the different academics who come to the area to do fieldwork—and to make it more attractive for others to come. The Shindig celebrates the community that supports the local museum, and the landowners who make fossil hunting possible. Last night was the annual Pitchfork Fondue, so named for the regulation, farmyard-sized pitchforks upon which steaks by the dozen are skewered and then lowered into 50-gallon cauldrons of boiling peanut oil, to delicious result. As a band played country music and beer flowed from the taps, the assembled academics, students and locals danced and mingled and traded tall tales into the wee hours of the warm and buggy night.

Early this morning, a caravan of sleepy MRF volunteers and staffers returned to Ekalaka to catch the day-long slate of distinguished speakers, including Lyson and Kirk Johnson. In the audience, along with interested locals, are fieldworkers from, among others, the Burpee Museum of Rockford, Illinois, the Los Angeles County Museum, the University of California, Carthage College in Pennsylvania, and the University of Maryland.

In the moments of fidgeting between presentations, one of the teens from the MRF group gets up from his chair and moves to the side of the sanctuary.

I join Jeremy Wyman against the wall. He has his cell phone out; per their MRF assignments, all four of the teen interns are live-covering the Shindig on various social media platforms. By way of greeting, I ask him what he’s up to.

“Resting my butt,” he says with a respectful smirk.

I ask about the theropod hand. What happened? Was it real?

Wyman shrugs. “It was nothing but plant matter, all crumbled up and packed together. We kind of jumped to a conclusion because it would be so cool to find a therapod hand.”

I ask if he’s disappointed about the theropod hand. Wyman shakes his head emphatically, no way.

“Being out here has actually changed my entire view on paleontology,” he says. “At first I was super into dinosaurs. But then coming out here and seeing all these important paleontologists doing research into fossilized plants and pollen, I realize that paleontology is a lot more than just dinosaurs. I feel like I’ve been missing something.”

This story is included in Sager’s latest collection, The Lonely Hedonist: True Tales of Sex, Drugs, Dinosaurs and Peter Dinklage, published in paperback and eBook on September 7.

*Isiah Newbins graduated high school in June, 2017 and in the fall will begin attending the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, where he will study biology with the intent of seeking a graduate degree in paleontology in the future.

*Jeremy Wyman graduated high school in June, 2017 and in the fall will begin attending the University of Pensylvania, where he will study paleobiology in the Earth and Environmental Science Department.

*Tyler Lyson continues to work at the Denver Museum, and is still engaged in ongoing studies of the K/T Boundary in Hell Creek, post-extinction fossils in South Africa, and other projects. This summer a new group visiting Marmarth excavated a 4,000 pound triceratops skull.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.