Unborn Turtles Actively Regulate Their Own Temperature

Before hatching, a baby turtle can deliberately move between warm and cool patches within its egg—a behavior that may help determine its gender

Chinese pond turtles sunning themselves to regulate their body temperatures. Photo by Flickr user Peter

Visit a sunny pond in a meadow, park or zoo and you’ll likely see turtles basking on logs and small lizards hanging out on warm rocks. If you’re in the south, you may even spot an alligator lazing on a bright patch of shore.

Ectotherms (better known as cold-blooded animals) such as these reptiles have to shuttle back and forth between shade and sun in order to manually regulate their body temperature. Insects, fish, amphibians and reptiles all do it. Now, new research suggests that these animals begin their temperature-regulating tasks much earlier than previously thought–while they are embryos encased in their eggs.

Previously, researchers thought of developing embryos as cut off from the outside world. But back in 2011, researchers found that Chinese soft-shelled turtle embryos could move between warmer or cooler patches in their eggs, though they lacked any feet at such an early stage of development. Some of the same Chinese and Australian researchers who published that original finding decided to investigate further to see just how deliberate these movements are.

“Do reptile embryos move away from dangerously high temperatures as well as towards warm temperatures?” the team, writing in the journal Biology Letters, wondered. “And is such embryonic movement due to active thermoregulation, or (more simply) to passive embryonic repositioning caused by local heat-induced changes in viscosity of fluids within the egg?”

In other words, are unborn reptiles purposefully moving from one spot to another within their eggs, much like an adult animal does? The team decided to investigate these questions by experimenting on turtle embryos. They incubated 125 eggs from Chinese three-keeled pond turtles. They randomly assigned each of the eggs to one of five temperature groups: constant temperature, hot on top/cool on the bottom, or at a range of heats directed towards one end of the egg.

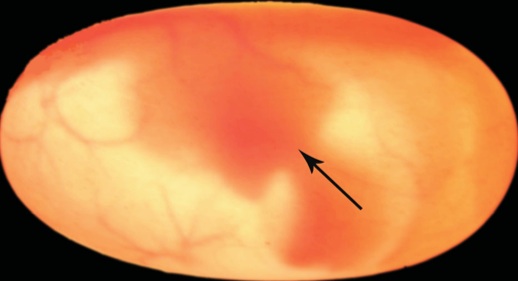

An embryo positioned in the center of one of the researchers’ eggs. Photo by Zhao et al, Biology Letters

When they began the experiment, most embryos sat in the middle of their eggs. A week after exposing them to the different temperature groups, the team again measured the baby turtles’ positioning within the eggs. At the 10-day mark, the researchers again measured the turtles’ positions, and then injected half of the eggs with a poison that euthanized those developing embryos. Finally, after another week, they took one last measurement of the developing turtles and euthanized turtles.

The turtles within the eggs held at constant temperature or those that were in the “warm on the top/cool on the bottom” group tended not to shift around in their eggs, the researchers found. Those belonging to the groups that experienced warm temperatures only on one end of their egg, however, did move around. They gravitated towards warm conditions (84-86°F), but if things heated up too extremely (91°F), they edged towards the cooler side of their egg. Crucially, the embryos that the researchers euthanized stopped moving after receiving the dose of poison. This shows that the embryos themselves, not some passive physical process, are doing the shifting.

The turtle embryos, the researchers note, behave much like adult reptiles do when thermoregulating their bodies. They warm up and cool down by moving toward or away from heat sources. For species like turtles, temperature during development plays an important part of determining the embryo’s sex. Turtle nests, which are buried in the sand, often experience a range of different temperatures, so embryos could be playing a role in determining their own gender, edging towards the cooler side of the egg if they feel like becoming a male, or the warmer side if they’re more female-inclined, the authors write.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)