To Understand the Elusive Musk Ox, Researchers Must Become Its Worst Fear

How posing as a grizzly helps one biologist grasp the threats facing this ancient beast

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/44/0d/440d4152-d6da-42de-b494-0962bfd3b865/slide4.jpg)

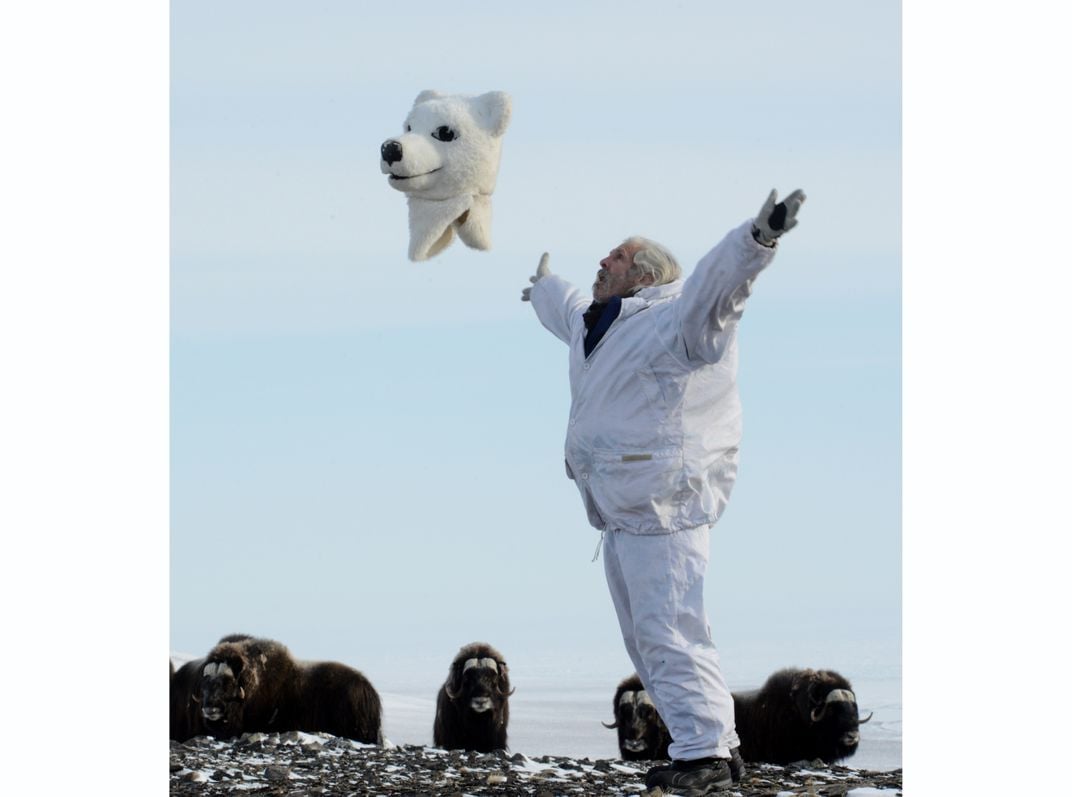

Joel Berger is on the hunt. Crouching on a snow-covered hillside, the conservation biologist sports a full-length cape of brown faux fur and what looks to be an oversized teddy bear head perched on a stake. Holding the head aloft in one hand, he begins creeping over the hill’s crest toward his target: a herd of huddling musk oxen.

It’s all part of a plan that Berger, who is the wildlife conservation chair at Colorado State University, has devised to help protect the enigmatic animal that roams the Alaskan wilderness. He slowly approaches the unsuspecting herd and makes note of how the musk oxen react. At what distance do they look his way? Do they run away, or stand their ground and face him? Do they charge? Each of their reactions will give him vital clues to the behavior of what has been a notoriously elusive study subject.

Weighing up to 800 pounds, the Arctic musk ox resembles a smaller, woollier cousin of the iconic American bison. But their name is a misnomer; the creatures are more closely related to sheep and goats than oxen. These quadrupeds are perfectly adapted to the remote Arctic wasteland, sporting a coat of thick fur that contains an insulating under layer to seal them away from harsh temperatures.

Perhaps most astonishing is how ancient these beasts are, having stomped across the tundra for a quarter of a million years relatively unchanged. "They roamed North America when there were giant lions, when there were woolly mammoths," Berger told NPR's Science Friday earlier this year, awe evident in his voice. "And they're the ones that have hung on." They travel in herds of 10 or more, scrounging the barren landscape in search of lichen, grasses, roots and moss.

But despite their adaptations and resilience, musk oxen face many modern threats, among them human hunting, getting eaten by predators like grizzlies and wolves, and the steady effects of climate change. Extreme weather events—dumps of snow, freezing rain or high temperatures that create snowy slush—are especially tough on musk oxen. “With their short legs and squat bodies," they can't easily bound away like a caribou, explains Jim Lawler, an ecologist with the National Parks Service.

In the 19th century, over-hunting these beasts for their hides and meat led to a statewide musk ox extinction—deemed "one of the tragedies of our generation" in a 1923 New York Times article. At the time, just 100 musk oxen remained in North America, trudging across the Canadian Arctic. In 1930, the U.S. government shipped 34 animals from Greenland to Alaska's Nunivak Island, hoping to save a dwindling species.

It worked: by 2000, roughly 4,000 of the charismatic beasts roamed the Alaskan tundra. Yet in recent years that growth has slowed, and some populations have even started to decline.

Which brings us back to how little we know about musk oxen. Thanks to their tendency to live in sparse groupings in remote regions that are near-impossible for humans or vehicles to traverse, no one knows the reason for today’s mysterious decline. The first part of untangling the mystery is to figure out basic musk ox behavior, including how they respond to predators.

This is why Berger is out in the Arctic cold, dressed up as a musk ox’s worst nightmare.

Becoming the other

Donning a head-to-toe grizzly bear costume to stalk musk oxen wasn’t Berger’s initial plan. He’d been working with these animals in the field since 2008, studying how climate change was impacting the herds. Along with the National Parks Service, he spent several years tracking the herds with radio collars and watching from a distance how they fared in several regions of Western Alaska.

During this work, scientists began to notice that many herds lacked males. This was likely due to hunting, they surmised. In addition to recreational trophy hunting, musk oxen are important to Alaskan subsistence hunters, and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game grants a limited number of permits each year for taking a male musk ox. This is a common wildlife management strategy, explains Lawler: "You protect the females because they're your breeding stock."

But as the male populations declined, park officials began finding that female musk ox and their babies were also dying.

In 2013, a study published in PlosOne by members of the National Park Service and Alaska's Department of Fish and Game suggested that gender could be playing a key role. In other animals like baboons and zebras, males hold an important part in deterring predators, either by making alarm calls or staying behind to fight. But no one knew whether musk ox had similar gender roles, and the study quickly came under criticism for a lack of direct evidence supporting the link, says Lawler.

That’s when Berger had his idea. He recalls having a conversation with his park service colleagues about how difficult these interactions would be to study. “Are there ways we can get into the mind of a musk ox?’” he thought. And then it hit him: He could become a grizzly bear. "Joel took that kernel of an idea and ran with it," says Lawler.

This wouldn't be the first time Berger had walked in another creature’s skin in the name of science. Two decades earlier, he was investigating how carnivore reintroduction programs for predators, such as wolves and grizzlies, were affecting the flight behavior of the moose. In this case, he dressed up as the prey, donning the costume of a moose. Then, he covertly plunked down samples of urine and feces from predators to see if the real moose reacted to the scent.

It turns out that the creatures learned from past experiences: Mothers who had lost young to predators immediately took notice, while those who lost calves to other causes remained “blissfully ignorant” of the danger, he says.

To be a grizzly, Berger would need an inexpensive and extremely durable design that could withstand being bounced around "across permafrost, across rocks, across ice, up and over mountains and through canyons," he explains. The most realistic Hollywood costumes cost thousands of dollars, he says, and he couldn't find anyone willing to "lend one on behalf of science."

So Berger, who is also a senior scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society, turned to the WCS' Bronx Zoo to borrow a his teddy-bear-like ensemble. He then recruited a graduate student to make a caribou garment, so he could test how the musk oxen would react to a faux predator versus an unthreatening fellow ungulate.

After comparing the two disguises in the field, he found that the bear deception worked. When dressed as a caribou, he's largely ignored. But when he dons his grizzly suit, the “musk oxen certainly become more nervous,” he says. Now it was time to start gathering data.

The trouble with drones

Playing animal dress-up is far from a popular method for studying elusive creatures. More common strategies include footprint tracking and GPS collars, and most recently, drones. Capable of carrying an assortment of cameras and sensors, drones have grown in popularity for tracking elusive creatures or mapping hard-to-reach terrains. They’ve even been deployed as sample collectors to collect, among other things, whale snot.

But drones are far from perfect when it comes to understanding the complex predator-prey drama that unfolds between bear and musk ox, for several reasons.

They’re expensive, challenging to operate and finicky in adverse weather. "You can't have it all," says Mary Cummings, a mechanical engineer at Duke University who has worked with drones as a wildlife management tool in Gabon, Africa. Cummings found that the heat and humidity of Africa caused the machines to burst into flame. Meanwhile, Berger worries the Arctic cold would diminish battery life.

Moreover, when studying elusive creatures, the key is to leave them undisturbed so you can witness their natural behavior. But drones can cause creatures distress. Cummings learned this firsthand while tracking African elephants from the air. Upon the drone's approach, the elephants trunks rose up. "You could tell they were trying to figure out what was happening," she says. As the drones got closer, elephants began to scatter, with one even slinging mud at the noisemaker.

The problem, the researchers later realized, was that the drone mimics the creatures’ only nemesis: the African bee.

"Drones have kind of this cool cache," says Cummings. But she worries we've gone a little drone-crazy. "I can't open my email inbox without some new announcement that drones are going to be used in some new crazy way that's going to solve all our problems," she says. Berger agrees. "Sometimes we lose sight about the animals because we are so armed with the idea of a technological fix," he adds.

Another option for tracking hard-to-find animals is hiding motion-activated cameras that can snap images or video of unsuspecting subjects. These cameras exploded on the wildlife research scene after the introduction of the infrared trigger in the 1990s, and have provided unprecedented glimpses into the daily lives of wild animals ever since.

For musk oxen, however, observing from the sky or from covert cameras on the ground wasn't going to cut it.

Musk oxen are scarce. But even scarcer are records of bears or wolves preying on the massive creatures. In the last 130 years, Berger has found just two documented cases. That meant that to understand musk ox herd dynamics, Berger needed to get up close and personal with the burly beasts—even if doing so could put him in great personal danger. “We can’t wait another 130 years to solve this one,” he says.

When he first suggested his study technique, some of Berger’s colleagues laughed. But his idea was serious. By dressing as a grizzly, he hoped to simulate these otherwise rare interactions and study how musk ox react to threats—intimate details that would be missed by most other common study methods.

It's the kind of out-of-the-box thinking that has helped Berger tackle tough conservation questions throughout his career. "We call it Berger-ology," says Clayton Miller, a fellow wildlife researcher at WCS, "because you really have no idea what's going to come out of his mouth and somehow he ties it all together beautifully."

Risks of the trade

When Berger started his work, no one knew what to expect. "People don't go out and hang out with musk ox in the winter," he says. Which makes sense, considering their formidable size and helmet-like set of horns. When they spot a predator, musk oxen face the threat head on, lining up or forming a circle side-by-side with their young tucked behind. If the threat persists, a lone musk ox will charge.

Because of the real possibility that Berger would be killed, the park service was initially reluctant to approve permits for the work. Lawler recalls arguing on behalf of Berger’s work to his park service colleagues. "Joel's got this reputation for … these wacky hair-brained ideas," he remembers telling them. "But I think you have to do these kinds of far out things to make good advances. What the heck, why not?"

Eventually the organization relented, taking safety measures including sending out a local guide armed with a gun to assist Berger.

Besides the danger, Berger soon found that stalking musk ox is slow-going and often painful work. On average, he can only watch one group each day. To maintain the bear routine, he remains hunched over, scrambling over rocks and snow for nearly a mile in sub-zero temperatures and freezing winds. He sits at a "perilously close" distance to the musk ox, which puts him on edge.

Between the physical challenge and the nerves, each approach leaves him completely exhausted. "When you are feeling really frostbitten, it’s hard to keep doing it," he says.

But by weathering these hardships, Berger has finally started to learn what makes a musk ox tick. He can now sense when they're nervous, when they'll charge and when it's time to abort his mission. (When things are looking tense, he stands up and throws his faux head in one direction and his cape in the other. This momentarily confuses the charging musk ox, halting them in their tracks.)

So far he’s been charged by seven male musk oxen, never by a female—suggesting that musk oxen do indeed have distinct gender roles in the pack. Moreover, he’s found, the presence of males changes the behavior of the herd: When the group lacks males, the females all flee. This is dangerous because, as any outdoor training course will tell you, “you don't run from a [grizzly] bear," says Berger. When the herds bolt, musk oxen—particularly babies—get eaten.

The polar bear that wasn't

The charismatic polar bear has long been the poster child of Arctic climate change. Compared to musk ox, “they’re a more direct signal to climate,” says Berger. Polar bears need sea ice to forage for food, and as Earth warms, sea ice disappears. This means that tracking polar bear populations and health gives scientists a window into the impacts of climate change. Their luminous white fur, cuddly-looking cubs and characteristic lumber only make them more ideal as animal celebrities.

As a result, much of the conservation attention—and funding—has been directed toward polar bear research. Yet Berger argues that musk ox are also a significant piece of the puzzle. "Musk ox are the land component of [the] polar equation," Berger explains. Though their connection to climate is less obvious, the impacts could be just as deadly for these brawny beasts.

Musk oxen and their ancestors have lived in frosty climates for millennia. "If any species might be expected to be affected by warming temperatures, it might be them," he says.

Moreover, musk oxen have their own charisma—it’s just rare that people get to see them close enough to witness it. The easiest time to spot them, says Berger, is during winter, when the animals' dark tresses stand in stark contrast to the snowy white backdrop. "When you see black dots scattered across the hillside, they are as magic," he says.

From Greenland to Canada, musk oxen around the world face very different challenges. On Wrangle Island, a Russian nature preserve in the Arctic Ocean, the animals are facing increased encounters with deadly polar bears, but less direct climate impacts. To get a more complete picture of musk oxen globally, Berger is now using similar methods to study predator interactions with the herds on this remote island, comparing how the creatures cope with threats.

"We can’t do conservation if we don’t know what the problems are," says Berger. "And we don’t know what the problems are if we don’t study them." By becoming a member of their ecosystem, Berger hopes to face these threats head on. And perhaps his work will help the musk ox do the same.

"We won't know if we don't try," he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)