Unraveling the Mysteries of the Ocean Sunfish

Marine biologist Tierney Thys and researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium are learning more about one of the largest jellyfish eaters in the sea

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ocean-Sunfish-Tierney-Thys-with-a-tagged-mola-631.jpg)

Part of the appeal of the ocean sunfish, or Mola mola, is its unusual shape. The heaviest bony fish in the world, it can grow more than 10 feet long and pack on a whopping 5,000 pounds, and yet its flat body, which is taller than it is long, has no real tail to speak of. (“Mola” means “millstone” in Latin and refers to the fish’s disc-like physique.) To motor along, the fish uses powerful dorsal and anal fins.

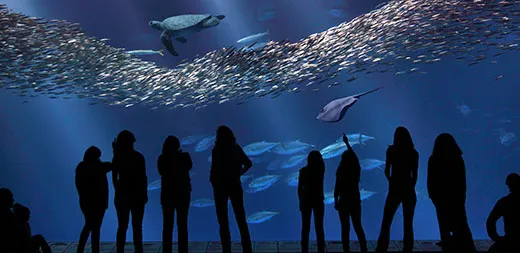

The mola is something of a star at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, the only facility in North America to currently exhibit the bizarre-looking fish. “You just don’t see anything like that,” says John O’Sullivan, curator of field operations at the aquarium. When the nearly four-foot-long sunfish swims slowly across the two-story window of the Open Sea gallery, its large eyes pivoting as it travels, it is as if the whole building shifts with the weight of people gathering in awe, he says.

For being so visually arresting (it is on the bucket list of many scuba divers), the mola is a bit of a mystery; very little is known about its biology and behavior. Tierney Thys, for one, is trying to change this.

“I always feel that nature reveals some of her greatest secrets in her extreme forms,” says Thys at her home perched like a tree house in the hills of Carmel, California. With reports suggesting that jellyfish may be on the rise, the marine biologist is even more compelled to understand the lives of molas, which are voracious jelly eaters.

If the sparkle in her eye when she talks about her many encounters with wild molas doesn’t give away her passion for the species, her impressive collection of tchotchkes does. Thys shows me playing cards, postage stamps and chopsticks decorated with molas, stuffed animals, even crackers (like Pepperidge Farm’s “Goldfish,” only shaped like sunfish), laughing at the range of mola products she has found in her travels around the world studying the fish.

Thys’s introduction to the mola came in the early 1990s when she came across a photo of one while doing graduate work in fish biomechanics at Duke University. A tuna, she explains, is sleek, like a torpedo; its form gives away its function: to travel great distances with speed. “But you look at a mola,” she says, “and you think, what is going on with you?”

Molas emerged between 45 million and 35 million years ago, after the dinosaurs disappeared and at a time when whales still had legs. A group of puffer fishes—“built like little tanks,” says Thys—left coral reefs for the open ocean. Over time, their clunky bodies became progressively more “abridged,” but never as streamlined as some other deep-sea fishes. “You can only divorce yourself from your bloodlines so much,” says Thys. “If your grandmother had a big bottom and your mother had a big bottom, you are most likely going to have a big bottom. There is not much you can do!”

From her advisor, she learned that the Monterey Bay Aquarium was on the cusp of being able to display molas. The aquarists had a few fish in quarantine tanks, and Thys was able to spend some time at the aquarium studying their swimming mechanics and anatomy.

In 1998, Thys moved to the Monterey Peninsula, where she worked as a science editor and later director of research at Sea Studios Foundation, a documentary film company with an environmental focus. She served as the science editor for the foundation’s award-winning series “The Shape of Life,” about evolution in the animal world, which aired on PBS; the mola had a cameo. Meanwhile, Thys rekindled her relationship with the aquarium.

At the aquarium, O’Sullivan tested tags on captive molas, and in 2000, he and Thys began tagging wild molas in southern California. Chuck Farwell, curator of pelagic fishes at the aquarium, had established a relationship with Kamogawa Sea World in Japan, and he and Thys began tagging there as well. The Japanese have been the leaders in exhibiting molas. Historically, the culture holds the mola, known as manbou, in high regard. In the 17th and 18th centuries, people gave the fish to shoguns in the form of tax payments. Today the mola is Kamogawa’s official town mascot.

Thys has since tagged and tracked molas in Taiwan, South Africa, Bali and the Galapagos Islands, and in doing so, she has become one of the world’s leading experts on the fish. She runs a website, Oceansunfish.org, which serves as an information hub on the species, and she asks citizen scientists to report any sightings. “Nearly every day I have people reporting,” says Thys. Molas have been seen north of the Arctic Circle and as far south as Chile and Australia. “I just got a report from Mozambique,” she says. “I would love to go to Mozambique.”

Since ocean sunfish are neither known to be endangered nor are they commercially important (outside of Asia, particularly Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines, where they are eaten), research funding can be hard to come by. Thys scrapes together small grants and squeezes tagging expeditions into her busy schedule as a mother of two, National Geographic Explorer and science media filmmaker and consultant on several marine education projects. “I moonlight on the sunfish,” she says.

The methods for tagging vary by location. In California, Thys and her Monterey Bay Aquarium colleagues often use a spotter plane. From the air, the pilot spies the white outlines of molas and radios their location to a team in a boat below. The ocean sunfish owes its name to its tendency to bask in the sunlight near the surface. In some cases, gulls on the water’s surface also indicate the presence of molas, since Western gulls and California gulls clean the fish of the dozens of species of parasites that live on them. In Bali, where molas don’t spend much time on the surface, Thys and her team tag the fish underwater with modified spear guns. But in other places, it is just a matter of scanning the surface from the bow of a Zodiac boat. “They are just goofy,” says Thys. “They stick their fin out of the water and wave, ‘Hello, I am over here.’ ”

Once a mola is spotted, the group speeds up to it and traps it in a hand net. Snorkelers wearing wetsuits and gloves to protect against the fish’s spiny skin (Thys compares it to “36 grit sandpaper”) jump into the water and corral the fish alongside the boat, while someone inserts the tag at the base of the fish’s dorsal fin.

This past September, Thys had what she considers one of the most amazing sunfish encounters of her career. At a place called Punta Vicente Roca, on Isabela Island in the Galapagos, she and her team came upon a group of about 25 molas, each about five feet long, while diving at depths of up to 90 feet. “I didn’t even know where to look,” says Thys, showing me video footage she took with a small, waterproof camera mounted like a headlamp on a strap around her head. Adult sunfish are loners and do not school, so it is rare to see more than a couple at time. But this spot was a cleaning station. The molas were suspended in a trance-like state, their heads pointed upward while juvenile hogfish pulled off their parasites. “It was awesome,” she adds.

Thys likens molas to “big, slobbery Labradors.” (In addition to parasites, the fish are covered in mucus.) O’Sullivan calls the slow-moving, awkward fish “the Eeyore of the fish world.” Needless to say, molas are harmless and generally unperturbed by humans. Wild encounters, like this one, make Thys wish she could follow the fish to see where they go and what they are up to. That is where satellite tags come into play.

Most of the time, Thys uses pop-up archival transmitting (PAT) tags that release from the fish at a pre-programmed time, drift to the surface and transmit data about the fish’s movements—its locations and depths, as well as water temperatures—by satellite. In the Galapagos, however, she tagged five sunfish with acoustic tags; on two of them, she also placed Fastloc GPS tags. An array of underwater listening stations detects the unique signal of each acoustic tag, while GPS tags reveal sunfish locations in real time. One of the GPS tags, programmed for nine months, released after less than two, but it revealed some interesting details. The fish had traveled nearly 1,700 miles from the archipelago, for reasons unknown, and had made a record dive down to 3,600 feet. Another Fastloc tag is due to pop off this month; its real-time reporting capabilities failed but it could still relay some data.

“We are starting to unravel a bunch of the mysteries,” says Thys. Pockets of mola researchers around the world have found that molas are powerful swimmers that buck ocean currents—dispelling a myth that they are lethargic drifters. Scientists are looking into what factors drive molas’ migrations, though one seems to be temperature. The fish prefer water ranging from 55 to 62 degrees Fahrenheit. Molas also dive up to 40 times a day. They descend to depths, on average, of 310 to 560 feet, most likely to forage in a food-rich zone called the deep scattering layer. Presumably to recover from temperatures as low as 35 degrees Fahrenheit at that level, they then sunbathe at the surface.

But every discovery, in turn, leads to more questions. Molas are found in temperate and tropic waters worldwide, but how big is the total population? The fish make up a large percentage of the unintended catch in fisheries in California, South Africa and the Mediterranean. How is that bycatch impacting overall numbers? Female molas can carry an estimated 300 million eggs, making them the most fecund fish in the sea. Where do they spawn, and at what age?

Molas eat gelatinous zooplankton, such as moon jellies, as well as squid, crustaceans and small fish, including hake, and their eating habits may change as they grow. But how much do they have to eat to keep their portly figure?

In its lifetime, a mola grows from a larva one-tenth of an inch long to an adult more than 60 million times its starting weight. That is comparable to a human baby ultimately weighing the equivalent of six Titanics. But what is the fish’s average lifespan? By extension, at what rate do they grow in the wild?

Michael Howard, head of the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s mola husbandry team, would certainly like to know the answer to that last one.

At the aquarium, Howard takes me to the top lip of the million-gallon Open Sea tank, where I have a front row seat to a mola feeding. The event is carefully orchestrated, as is just about everything related to an exhibition where hammerhead sharks, sea turtles, tunas, huge schools of sardines and other animals are meant to peacefully coexist. The turtles are stationed in one area while a staff member, crouched on a gangplank over the tank, dunks a pole with a ball on the end of it into the water. The mola is trained to come to the target, expecting a meal. The fish rises, a murky shadow at first. Then, once the mola’s botoxed-looking lips break the surface, the feeder drops some squid, shrimp and a gelatin product into its gaping mouth.

The aquarium has exhibited molas fairly consistently for 16 years, but in many ways, the husbandry staff is still shooting from the hip—especially when it comes to managing the fish’s growth in captivity.

In the late 1990s, a 57-pound mola ballooned to 880 pounds in just 14 months. The fish had to be airlifted out of the aquarium by helicopter and released back into the bay. “It worked great, and it was a rush. It took seven months to plan. We had 24 people on staff and FAA approval to cordon off the building that day we released it,” says O’Sullivan. “It is a great story. But wouldn’t it be better if we just got the animal up to half that weight, had a much more relaxed deaccession, replaced it with another animal a fraction of its size and started the whole process over?”

Howard, who has led the program since 2007, has been working toward this end. He and his team conduct ongoing captive growth studies; they record the mass of each type of food fed to the mola at its twice-daily feedings and follow up with routine health exams every two or three months, making any necessary adjustments in the fish’s diet. Each day, they aim to feed the mola a ration of food equal to 1 to 3 percent of its body weight. A few years ago, aquarists captured some moon jellies from the bay and had them analyzed. With the results, they worked with a company to produce a comparable gelatin product comprised of 90 percent water. “That really helps us get the daily volume up while keeping calories low,” says Howard. Depending on their stage in life, molas require only three to ten calories per kilogram of animal mass. To put that into perspective, adult humans need 25 to 35 calories per kilogram. Tunas at the aquarium get 30 calories per kilogram, and otters get 140 calories per kilogram. On the new diet, the aquarium’s last mola gained an average of .28 kilograms per day, whereas the airlifted mola nearly quadrupled that rate.

“As long as a mola’s behavior is healthy, we can consider working and caring for the fish until it approaches about six feet in length,” says Howard. That usually equates to a two-and-a-half-year stay. When it comes time for the fish to be released, which is always the end goal, says Howard, the team can then feasibly hoist the mola out of the tank on a stretcher, place it in a holding tank, first on a truck and then on a research vessel, and let it go a few miles offshore.

For Howard, the mola has been the trickiest species he has encountered in his 15 years of aquarium experience. “But who doesn’t enjoy a good challenge?” he says.

The peculiar fish prompts a slew of questions from aquarium visitors—about the species and the ocean in general. “If that happens,” says O’Sullivan, “then we are being successful in our mission.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)