Unwelcome Guests

A new strategy to curb the spread of gypsy moths

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/gypsy_larva.jpg)

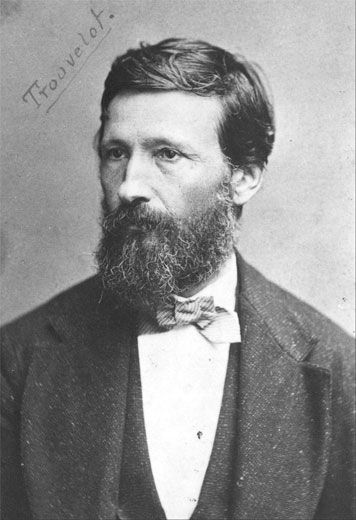

In the late 1860s, an amateur entomologist named Etienne Trouvelot accidentally released the Eurasian gypsy moth, a notorious defoliator, into the United States. That small event caused a major insect invasion: The moth has since spread across more than 385,000 square miles—an area nearly one-and-a-half times the size of Texas.

Now, a team of researchers has discovered a pattern in the moth's advance that might go a long way toward curbing the invasion— a battle that has cost roughly $200 million in the past 20 years.

By studying records of the moths dating back to 1924, Andrew Liebhold of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and his colleagues noticed that insects invade new areas in four-year pulses.

"Nobody suspected it was possible to get pulsed invasions," says Greg Dwyer of the University of Chicago, a gypsy moth expert since 1990 who was not part of the research team.

Liebhold's team found that the moth can't establish a home in a new territory unless a certain number of insects settle at once. Moth populations enter new areas slowly because female gypsy moths don't fly. Most moth relocation comes from hitchhiking: they lay eggs on cars that carry the insects to a new location. Every four years, enough moths enter a new habitat to establish a sustainable presence, the researchers report in the Nov. 16 Nature.

The new results suggest treating the fringes so that the population can never build enough mass to invade new territory. Current methods of moth control focus on eliminating new populations, says Liebhold. When the moths enter a new location, airplanes spray the invaded region with flakes that release the female mating pheromone, says Liebhold. These flakes disrupt the ability of males to locate females.

"We know we can't stop the spread," says Liebhold, "but we can slow it."

The gypsy moth problem began innocently enough. Trouvelot brought the insect home to Medford, Mass., after visiting his native France. Some of the insects escaped from nets and cages in his backyard in 1868 or 1869. Unable to convince anyone of the gravity of the situation, Trouvelot quit insect-keeping, became an accomplished astronomer and returned to France around 1880, right when the first gypsy moth outbreak hit New England.

Early efforts to curb that outbreak ranged from ineffective to disastrous. In 1904, forest service workers introduced a fungus called Entomophaga maimaiga, which kills the moth during the caterpillar stage. For unknown reasons, the fungus simply disappeared. So, beginning in the 1920s, workers barraged the moth with the harmful pesticide DDT — also to no avail.

In 1988, federal and state governments laid a grid of traps from Maine to west Minnesota and south to North Carolina to track the moth. This effort helped cut the moth's annual spread in half, but the species still advances an average of six miles a year.

And the potential for more damage remains, says Liebhold. Right now the moth only occupies about a third of its potential habitat, he estimates. "It probably hasn't even gotten to its best habitats yet."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)