VIDEO: Watch This Carnivorous Plant Fling an Insect Into Its Mouth

A small plant native to Australia features two sets of touch-sensitive tentacles to catapult insects towards its digestive concavity and then draw them in deeper

![]()

Most plants move so slowly that we can’t even see them. One plant, though, moves so quickly that if you blink at the wrong moment you could miss it entirely. When an insect lands on one of its touch-sensitive tentacles, Drosera glanduligera, a small carnivorous plant from southern Australia, snaps into action, flinging its prey into its leaf trap (two seconds into the video above). It might not look like much, but it’s one of the fastest trapping mechanisms known in the plant kingdom.

Botanists have known that D. glanduligera had a unique trapping method since the 1970s, but unlike the plant’s famous cousin, the Venus flytrap, scientists have only now examined how it accomplishes the feat. The findings of a group of German scientists who used microscopes and high-speed cameras to document the technique were published today in the online journal PLOS ONE.

To figure out exactly how the plant captures its prey, the researchers grew a crop of seven plants and fed them fruit flies while carefully filming. They also used a fine nylon thread in experiments to activate the plant’s touch-sensitive tentacles and measure just how long they take to respond to contact.

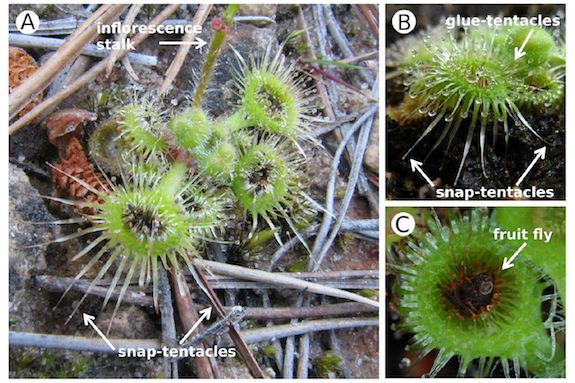

The researchers discovered that the plant has two types of tentacles: non-sticky, peripheral snap-tentacles that fling the insect prey towards the center, along with sticky, glue-tentacles that slowly draw the plant’s meal in towards the depression of the concave leaf, where it is slowly digested by enzymes over the course of days.

The plant features both quick-acting snap-tentacles and slow-moving glue-tentacles to fling an insect into its digestive concavity and then pull it in deeper. Image via PLOS ONE

After sensing contact, the plant’s snap-tentacles take just 400 milliseconds before springing into action. When they do, they bend at a flex point halfway down and swiftly fling a fly or ant into the center at speeds as fast as 0.17 meters per second. The extremely sticky glue that coats the surfaces of the secondary set of tentacles mean that the hapless insect has no chance of escaping.

The rapid bending and flicking motion of the tentacles, the researchers speculate, is likely enabled by some sort of hydraulic transport system, in which water is quickly moved between the plant’s cells. Cells that lose water suddenly contract, while cells that gain water expand, accounting for the sudden bending of the tentacle upon contact.

This hypothesis is also supported by the fact that, once a tentacle activates, it cannot retract to its original position and fling another insect. The researchers guess that this might be caused by the fracturing of cells in the tentacle’s hinge zone, as they buckle as a result of the extremely fast bending they’re forced to undergo.

Since the plant is a fast-growing annual, though, it can grow new leaves and tentacles over the course of days, so this isn’t a huge penalty to pay for a nutritious meal. For the plant, the ability to consistently trap tasty flies and ants in its digestive concavity and obtain nutrients would likely have been a strong selective pressure in the process of evolving such quick-acting tentacles.

The plant’s two-part trapping mechanism is far more complex than observed in other related carnivorous plant species, which simply rely upon sticky leaves and tentacles to keep prey from escaping. D. glanduligera‘s technique, the researchers write, is “more accurately termed a catapult-flypaper-trap.”

Our thoughts? If you’ve got a bug problem at home, just plant your own. Seems like it’d be a great flyswatter replacement, with free entertainment to boot.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)