Viking Chess Pieces May Reveal Early Whale Hunts in Northern Europe

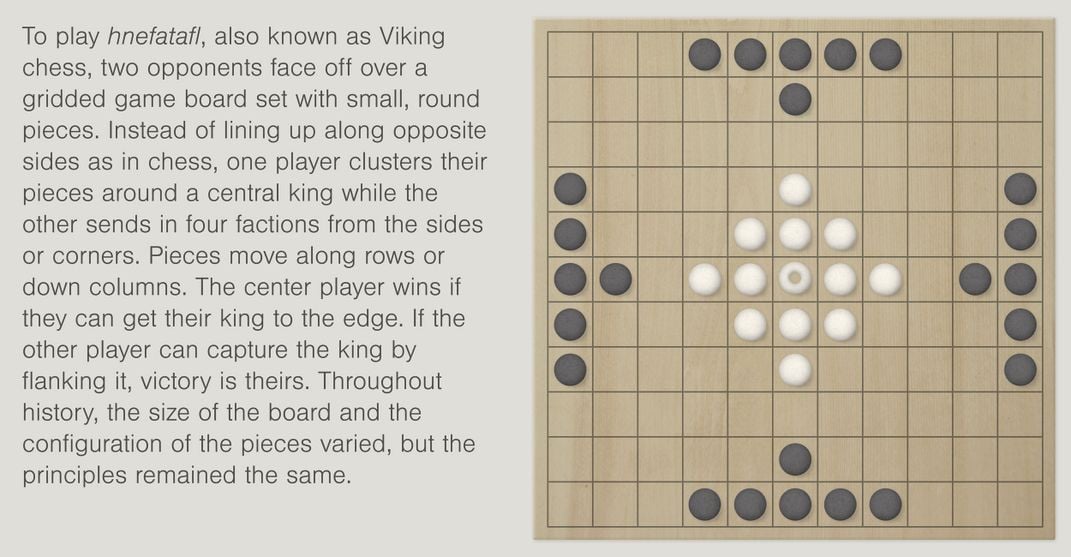

The board game hnefatafl, commonly called Viking chess, pits an attacking player against another trying to defend the king

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/6e/c96ed25b-63b6-43f2-afc8-3c52e5809a52/header-viking-game-pieces.jpg)

This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

In central and eastern Sweden from 550 to 793 CE, just before the Viking Age, members of the Vendel culture were known for their fondness for boat burials, their wars, and their deep abiding love of hnefatafl.

Also known as Viking chess, hnefatafl is a board game in which a centrally located king is attacked from all sides. The game wasn’t exclusive to the Vendels—people across northern Europe faced off over the gridded board from at least 400 BCE until the 18th century. But during the Vendel period, love for the game was so great that some people literally took it to their graves. Now, a new analysis of some hnefatafl game pieces unearthed in Vendel burial sites offers unexpected insight into the possible emergence of industrial whaling in northern Europe.

For most of the game’s history, its small, pebble-like pieces were made of stone, antler, or bone from animals such as reindeer. But later, starting in the sixth century CE, Vendels across Sweden and the Åland Islands were buried with game pieces made of whale bone.

In the new research, Andreas Hennius, an archaeology doctoral candidate at Uppsala University in Sweden, and his colleagues traced the source of the whale bone by following a trail of evidence that led them to the edge of the Norwegian Sea about 1,000 kilometers north of the Vendels’ heartland in central Sweden.

Hennius thinks the whale bones used to make the game pieces were the product of early industrial whaling. If so, the pieces would be evidence of the earliest-known cases of whaling in what is today Scandinavia, and a sign of the growing trade routes and coastal resource use that paved the way for future Viking expansion.

To come to this striking conclusion, Hennius and his colleagues first had to find out where the whale bone was coming from. The Vendels weren’t whalers, Hennius says, so the pieces must have been imported. But from whom? The researchers also needed to confirm that the bone was the result of deliberate whaling, not just scavenged from stranded whales.

To answer these and other questions, Hennius drew on genetic analysis, other archaeological finds, and ancient texts.

The first clue that the game pieces were indeed a sign of early industrial whaling emerged from genetic analysis of the whale bone. Though several whale species swam in Scandinavian waters, most hnefatafl pieces were made from North Atlantic right whale bones. This suggests the bones were the result of systematic hunting rather than opportunistic scavenging, Hennius says.

Other clues came from the Vendel graves. Whale bone game pieces first were only in the graves of a few wealthy people. But later, a flood of whale bone hnefatafl pieces appeared in the graves of regular folks. “Not the poorest graves, but the middle-class graves,” Hennius says. To him, it seemed like a rare, prestigious commodity suddenly became available to the mass market. And that implied regular, reliable imports—an industry.

Early texts hinted at where that whaling industry might have been located, since it almost certainly wasn’t in the Vendel lands of central and eastern Sweden.

The first known written record of whaling in Scandinavia describes a ninth-century Norwegian tradesman named Óttarr. In his travels, he visited the royal courts of England, where records describe him bragging about his whaling prowess. Óttarr claimed that he and his friends caught 60 whales in two days near what is now Tromsø, Norway. Though Óttarr’s exploits date several centuries after the appearance of whale bone in Vendel graves, it suggests whaling may have been well established in northern Norway by the 800s CE.

It isn’t clear who was actually doing the difficult work of catching the whales, though it could have be any of the several groups of people living in northern Norway at the time, including the Sami. As for who was turning the whale bone into game pieces, that is also unknown. According to the researchers, it could have been the Sami or anyone along the long trade route south.

Hennius says further archaeological evidence also supports the idea of early whaling in northern Norway. Recently, other researchers discovered blubber rendering pits in the region, associated with the Sami, that date from about the time whale bone game pieces appeared farther south. The existence of these pits, Hennius says, implies the Sami were processing a steady supply of whales and not just the occasional stranding.

Hennius says all of this together—the Sami’s rendering pits, Óttarr’s exploits, the predominance of one species, and the presence of whale bone in middle-class graves—is “strong evidence that active whaling took place in northern Norway at this time,” and that the Vendels had established long-distance trade routes to ferry the material south.

Vicki Szabo, a historian at the University of North Carolina who studies medieval whaling across the North Atlantic, says Hennius and his colleagues make a good case for the existence of pre-Viking whaling in Scandinavia. “They’re linking ideas and trends that haven’t clearly been linked before,” she says.

Szabo’s own research suggests whaling in northern Norway was definitely feasible around 550 CE. After the collapse of the Roman Empire during the fifth century CE and the period of economic disruption that followed, it took time for societies across Europe to rebound. Szabo says whaling fits with a larger pattern of economic resurgence at the time.

As for the logistical challenges, Szabo says it’s unlikely these early whalers were out on the open ocean hunting whales from boats. Instead, hunters could have used poison-tipped spears, netted off narrow fjords, or driven whales onto shore.

Hennius is continuing to study the imported Vendel hnefatafl game pieces to see what else they can tell us about their origin and the trade routes on which they traveled. If the game pieces do, in fact, tell the tale of expanding coastal resource use in Norway, it is one of the first chapters in the dawning saga of Viking maritime dominance.

Related Stories from Hakai Magazine: