A Maze of Palatial Icebergs Has Floated Into a Washington, D.C. Museum

The new exhibition touches on design, landscape architecture, the life of icebergs and climate change

In the past few decades, icebergs have become a kind of potent visual metaphor for the threats posed by climate change. The ice dwindles while world leaders debate what should be done.

To the curious general public, however, how climate change affects icebergs and what that means can seem abstract. That's why the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. will offer a chance to visit an iceberg this summer. Fortunately, a harrowing helicopter ride isn't needed.

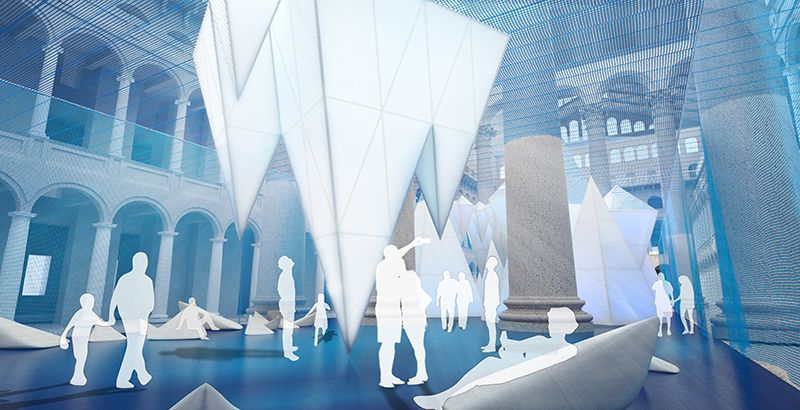

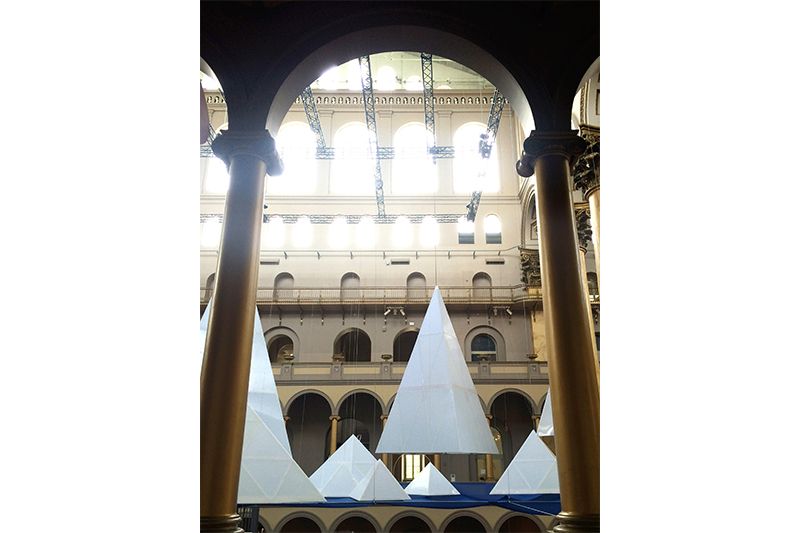

"Icebergs," an installation designed by the New York-based landscape architecture and urban design firm James Corner Field Operations, is an artistic interpretation of the underwater world of a glacial ice field. From July 2 through September 5, visitors will be able to explore underwater caves and grottos, and climb up a 56-foot-tall "bergy bit" to peer above the waterline—created by a suspended blue mesh bisecting the installation.

"What we are trying to do is create a very unique experience for the museum visitors, where they are able to immerse themselves in a landscape," says Isabel Castilla, a senior associate with James Corner and the project manager for "Icebergs."

The installation is intended to be a fun, family-oriented space to explore, with a mix of open spaces for gatherings of large groups of people and enclosures where a couple of people can chat more intimately. There will be a kiosk selling refreshments, a labyrinth for children to play and a slide providing a quick ride down from one of the icebergs. It is also a space for learning about the science surrounding icebergs. Ideally, the artificial icebergs will help visitors grasp what is happening to real icebergs at the planet's poles.

The firm studied photographs and research papers to understand icebergs. "We really got very involved in the iceberg world," Castilla says. "It is not something you know as much about as say, a forest ecosystem or a river." That deep delve into an icy world of glaciers gave Castilla and her colleagues a wealth of "ideas about design, color and light." They ended up choosing to work with materials they had never worked with before. The towering, pyramidal icebergs they created are built of reusable materials, such as polycarbonate paneling, a type of corrugated plastic often used in greenhouse construction.

Ironically, the National Building Museum's construction team recommended adding better ventilation to the largest icebergs, since they were so good at trapping heat inside, museum vice president of marketing Brett Rodgers says. These bergs won't melt, but visitors might've.

Another part of the installation features facts about icebergs printed on the bergs themselves. "[An] iceberg known as B15 was the largest iceberg in history, measuring 23 by 183 miles, nearly the size of Connecticut," details one of the factoids. "If melted, the B15 iceberg could fill Lake Michigan, or 133.7 million National Building Museums."

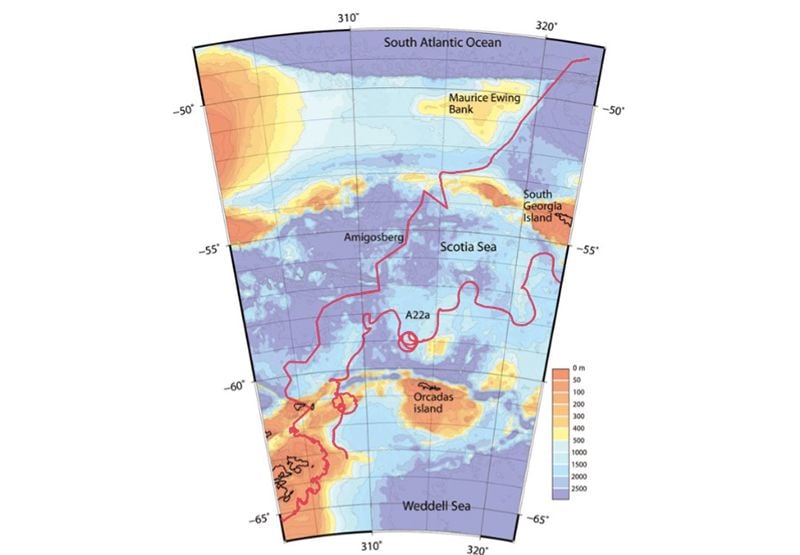

Scientists are still learning about the factors at play in and around icebergs. Researchers like Ted Scambos take extraordinary risks to study the masses and examine what their role is in the Earth's complicated ecosystem. In 2006, Scambos, a senior research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colorado, and his team sailed on the icebreaker ship A.R.A. Almirante Irizar to take them close to an iceberg measuring roughly seven by six miles and towering more than 100 feet above the sea surface. There, they climbed aboard a military-style helicopter. Their goal was to set foot on the iceberg, place a group of scientific instruments and then remotely track the berg's movement as it floated north to disintegrate.

But on March 4, 2006, "the light over the huge, very smooth berg was almost hopelessly flat—no features at all, like flying over an infinite bowl of milk," wrote Scambos in a research log for the mission at NSIDC's website.

How could the pilot land the team in those conditions? Throwing a small smoke bomb to the surface provided a point of reference, but it wasn't enough. During the first approach, the pilot couldn't quite judge the helicopter’s angle and one of the landing skids struck the iceberg's surface. "The massive helicopter staggered like a lumbering beast that had tripped," Scambos recalls. Fortunately, the pilot was able to recover, throw another smoke bomb and land safely.

Scambos and his team's measurements would provide them with information about how icebergs move and melt, a proxy for how the great Antarctic ice sheet may melt as the climate changes and global temperatures warm. For the scientists, the risk was well worth the opportunity to contribute to the collective knowledge about how ocean levels may rise and endanger coastal cities.

Scambos has seen how a melting iceberg leaves a trail of freshwater in its wake. As the ice sheet that gave birth to the berg moved over the Antarctic continent, it picked up dirt and dust rich in minerals like iron. When the traveling iceberg carries those nutrients out into the ocean, they nourish the water and provoke a bloom of marine algae. The algae in turn are gobbled by microscopic animals and small fish, which feed larger animals such as seals and whales. An iceberg creates its own ecosystem.

"They are really interesting in their own right," Scambos says. "It is an interaction between ocean and ice." He says he's glad that the installation will give the public a way to learn about icebergs.

For example, physical forces can act on icebergs in surprising ways. Scambos and the team described some of these movements after tracking the iceberg they nearly crash-landed on and other icebergs. The data they gathered allowed them to describe the dance of those huge but fragile plates of ice across the ocean in a paper published in the Journal of Glaciology.

Icebergs are steered by currents and wind, but a major influence on their movements that came as surprise to the scientists was the push and pull of the tides. The ebb and flow of the Earth's tides actually tilts the ocean surface into a gentle slope—a difference of just a few feet over 600 miles or so. An iceberg drifting out to sea inscribes curlicues and pirouettes on this inclined surface.

Some of the counterintuitive tracks that icebergs take has to do with their shape. Even though Antarctic icebergs are sometimes hundreds of feet thick, their wide expanse makes them thin in comparison to their volume. Scambos likens them to a thin leaf that drifts across the surface of the ocean.

(In Greenland and other locations in the Arctic, icebergs tend to be smaller chunks, as they break off from glaciers that aren't as large as the Antarctic ice sheet. In "Icebergs," the mountain-like constructions are inspired by Arctic, rather than Antarctic, bergs.)

Eventually, every iceberg's dance stops. Warm air flowing across the surface of the iceberg gives rise to ponds of meltwater that trickle down into ice cracks created by stresses when the berg was part of the larger ice sheet. The weight of liquid water forces the cracks apart and leads to the rapid disintegration of the iceberg.

The instrument station on the first iceberg toppled over into slush and meltwater in early November 2006, about eight months after Scambos and the team installed it. On November 21, GPS data showed the station "teetering on the edge of the crumbling iceberg," according to the NSIDC. Then it fell into the sea.

Watching the breakup of the icebergs taught Scambos and the other researchers about how ice shelves could collapse. "Within a year or so, we can see the equivalent of decades of evolution in a plate of ice that stays next to Antarctica and all the processes that are likely to occur," Scambos says.

As the ice shelf slides off the coast of Antarctica—a natural process that happens sort of like a tube of toothpaste being squeezed, but instead of a giant hand at work, the sheet moves thanks to its own weight—the ice braces against the rocky islands it encounters. When icebergs move and melt away, the movement of the glaciers that feed the ice shelf can accelerate and squeeze out more ice into the ocean to melt.

Scientists have estimated that an iceberg's lifetime from when snow first falls on a glacial field and is compressed to ice to when that ice melts into ocean can take as long as 3,000 years. Global climate change could speed that timeline up, ultimately sending more water into the oceans than is able to fall again as snow.

That's heavy information to absorb at a fun summer exhibit like "Icebergs," but the designers hope that the theme will seem natural . "We were designing the exhibit with the mission to speak to the general public about the built environment and the science," Castilla says. The icebergs are intended to be beautiful and simple, while still showcasing how the materials and shapes come together to create a useable space. In the same way, the science behind icebergs and climate change should emerge through the exhibit's educational facts and lectures on the subject of climate change.

After all, climate change is increasingly a part of everyday life. "It's less news and more something we are always aware of," says Castilla.