Want to Excite Your Inner Dinosaur Fan? Pack Your Bags for Alberta

Canada’s badlands are the place to see fantastic dinosaur fossils (and kitsch)—and eye-opening new evidence about the eve of their fall

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/31/97/31972153-15e4-4f12-bce0-eb8b4ff81f37/dec15_j03_dinosaurpark.jpg)

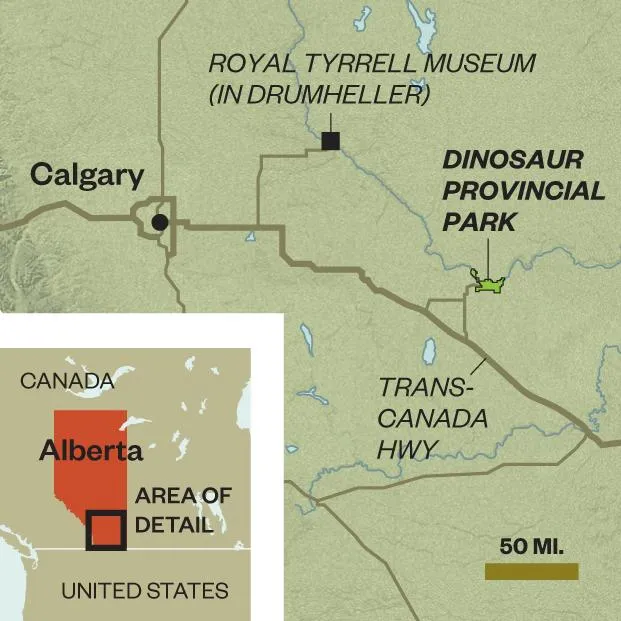

Drumheller, some 90 miles northeast of Calgary, Canada, looks like any one of a thousand western towns. Its quiet streets are lined with low-slung buildings and storefronts, a diner or two, a bank branch. A water tower rises over the scene, the town’s name painted on its barrel body in tall block letters. But it doesn’t take long to see what makes the place different.

“Bite Me,” reads a T-shirt in a gift shop window, a toothy cartoon T. rex yawning wide. Down the block, another storefront advertises—with no apparent concern for the anachronism—“Jurassic Laser Tag.” Sidewalks are painted with three-toed footprints the size of my head, and bright dinosaur sculptures—some covered with polka dots, others glowing fluorescent—stand on nearly every corner. A purple and red triceratops lifts its horned snout at the fire hall. A lime green apatosaurus sits upright on a bench across from the Greyhound depot.

Drumheller calls itself the Dinosaur Capital of the World, its devotion to paleontological research a point of immense pride. Hundreds of dinosaur skeletons have been found in the surrounding badlands, with fossils representing some 60 species from the late Cretaceous, the dinosaurs’ evolutionary peak. That’s a staggering 5 percent or more of all known dinosaur species.

Paleontologists have flocked to Alberta’s badlands for more than a century, beginning in 1910, when a local rancher got the attention of Barnum Brown, a fossil collector for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. After listening to the stories of giant bones discovered along the valley of the Red Deer River, which runs through Drumheller, Brown visited the site. Recognizing its value, he mounted full-scale expeditions with a flat-bottomed boat to serve as a mobile field station and sheets of netting as protection from mosquitoes—the start of the Great Canadian Dinosaur Rush. Within five years, the American Museum of Natural History alone had shipped out enough dinosaur bones to fill three-and-a-half freight cars.

Enthusiasm has not abated. Dinosaur Provincial Park was established in 1955 to protect valuable fossil beds, and even today, paleontologists make notable discoveries at a rate of nearly one per year. Recently, a paleontologist found the skeleton of a baby Chasmosaurus, a triceratops relative with an almost heart-shaped frill. It’s currently the most complete skeleton of a baby horn-faced dinosaur anywhere, and will be studied for clues to dinosaur growth and development.

My first stop on my dinosaur journey is the Royal Tyrrell Museum, a ten-minute drive from town, where many of the most prized fossils dug from Alberta’s badlands are on display. Built in 1985, the exhibition and research facility houses more than 150,000 fossil specimens, including the first partial skull of Atrociraptor marshalli, a feathered raptor believed to be a relative of the ancestor of birds; another triceratops relative whose horns did not stick outward but instead formed a massive bone across the top of the skull; and “Black Beauty,” an enormous T. rex skeleton—30 percent of the displayed bones are the real thing—stained by manganese during its millions of years in the ground.

I’ve visited once before, with my mother, as a dinosaur-obsessed 7-year-old. I remember the huge, bizarre skeletons, which are still plentiful and impressive. In one hallway I walk alongside the astonishing 70-foot-long Shastasaurus sikanniensis, a Triassic sea monster and the largest marine reptile ever discovered. As a child, I didn’t pay attention to how the exhibits were organized, but now I see that many of them connect in a chronological jaunt that spans 505 million years—the entire history of complex life on earth, putting into context the dinosaurs’ reign as well as our own species’ sliver of existence. You can easily see how we’re connected to these seemingly mythical beasts, since there’s no huge divide between our age and theirs. Our mammalian ancestors lived alongside the dinosaurs.

In a gallery devoted to the Burgess Shale, I learn how scientists have traced the great-great relatives of nearly every existing life-form, algae or mammal, to this major fossil formation in the Canadian Rockies. There’s another gallery devoted to the Devonian period; some scientists believe its mass extinction was just as severe as the dinosaur extinction, perhaps more for marine life.

The subject of large-scale extinctions came up when I spoke with a young tour guide named Graham Christensen, who says he moved to Drumheller for the sole purpose of volunteering at the museum and is now a paid employee. He has a plan for our species to escape the next mass extinction; he’s one of some 700 people on the shortlist for Mars One, an attempt at human settlement on Mars starting in 2025.

The Dinosaur Hall is still the main attraction, with skeletons mounted in lifelike poses: predators closing in on prey, armored herbivores facing down toothy carnivores. All the best-known dinosaurs from Steven Spielberg’s flick are here: duck-billed herbivores called hadrosaurs, dromaeosaurs (the family that includes velociraptor), triceratops and the king of them all, T. rex. The era during which they thrived, 70 million to 80 million years ago, as well as their last days, are represented in the rocks and soil of Alberta. “It really should have been called ‘Cretaceous Park,’” says François Therrien, one of the museum’s paleontologists.

Therrien is dressed head to toe in lightweight khaki: ball cap, button-down safari shirt and cargo pants. For some years he has been conducting field research that probes why the dinosaurs died out, and though the question has by now been answered to nearly everyone’s satisfaction, Therrien has been explaining an interesting twist on the theory. But first he has agreed to show me the telltale evidence for the main event.

A 45-minute drive northwest of the museum, we’re standing on the steep slope of the canyon carved by the Red Deer River, some 25 feet or so below prairie level. We’re on private land, but the property owners often give researchers access. In fact, Therrien says, this has become a sort of “pilgrimage site” for paleontologists. He scrapes away dirt to reveal a thin horizontal line of orangish clay. It’s the very debris that settled across earth’s surface after a giant asteroid or comet—some space colossus to be sure—struck Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula.

Many animals would have died almost immediately, from the intense heat generated by the collision and as debris blasted upward fell back to earth. Then there were the tsunamis and perhaps wildfires and, many scientists believe, a global winter. With dust blocking the sun, temperatures dropped and plants couldn’t photosynthesize. Food would have been scarce. About half of all living plant and animal families on the planet died off, dinosaurs included.

The line of sediment, generally known as the K-T boundary, divides two geologic periods: the Cretaceous and what was once known as the Tertiary (it’s gone out of fashion in favor of Paleogene). I pinch a little of the material between my thumb and index finger, almost expecting it to burn.

Some small portion of the layer can be traced to the hours immediately following the impact. And some, scientists can tell by the amount of iridium and other elements contained within, sifted slowly down over the course of a decade. In the inches and feet above, the soil holds a record of the life that survived, the life that rallied. Most notably, the once small mammals, never larger than a house cat, over time became more numerous and dominant, growing in size and diversity to fill the gap left in the natural pecking order.

Initially, Therrien says of the dinosaurs’ disappearance, “the big question was about the rate at which the extinction took place and the immediate aftermath of the impact.” But as scientists started to get a handle on the moment itself, other questions began to pile up. “Was diversity really high until the day of the impact, and then everything died out? Or was it more of a gradual thing, possibly in response to environmental change? Was there already a decline in the diversity of animals and plants?”

***

Paleontologists have long wondered whether dinosaurs succumbed to long-term effects of climate change, independent of any impact. Could climate changes have weakened the dinosaurs enough to make an otherwise survivable event truly disastrous?

Studies have documented wild temperature swings in the last years of the Cretaceous: first cooling and then substantial warming, along with sea level changes. It’s possible, according to recent research, that large herbivores, including duck-billed hadrosaurs and the ceratopsians (the family of triceratops), declined in the millions of years leading up to the extinction. With a drop in herbivores, carnivores might have had less to eat, making them more susceptible when the space rock hit. If so, the extinction story extends well below this thin orange line.

Shortly before I headed to Drumheller, I spoke with Brad Tucker, then head of visitor services at Dinosaur Provincial Park and now the executive director of Canadian Badlands, a tourism organization. “One of the things that makes Alberta so important when we study the history of the earth is the fact that along the Red Deer River we have the last ten million years of the dinosaurs recorded in the rocks,” he said. There’s a continuous story being told here. “There’s no other place on earth that has that record and that opportunity to study what was happening to the dinosaurs during that time.”

***

The Red Deer River carved deep into the prairie, exposing the geology in a way that offers a unique form of time travel. North of Drumheller, where I’d visited the K-T boundary, the geology speaks to 66 million years ago. In the town itself, the rocks date from 71 million to 72 million years ago. Driving southeast to Dinosaur Provincial Park, my final stop in my journey, some two hours away, the visible rocks have aged another four million years, further back into the dinosaurs’ reign.

During the summer season, park interpreters lead guided tours through the brown- and red-striped landscape with hills and cliffs resembling the wrinkled backs of sleeping dinosaurs. This is the only way to access the 80 percent of the roughly 30-square-mile park that is set aside for researchers. There are also bus tours of the badlands and multi-day excursions that have guests bedding in fully furnished trailers. I wandered the unrestricted portion of the park, set inside a wide loop road.

With my car the only one in the parking lot, I head off along the mile-long Badlands Trail. The narrow, gravel path twists into the hills until everything but badlands have vanished from view. I pause and do a slow turn. I swat at the mosquitoes, survivors from the Cretaceous themselves.

One of two fossil houses along the wide loop road is an impressive bone bed preserved under glass. In front of me is a headless but otherwise near-complete skeleton of a hadrosaur. Splayed out and still half-entombed in rock, it remains deeply connected to the land, to the river valley, to the cliffs where I’d touched that line of orange clay. The hadrosaurs are considered the deer of their day, numerous and widespread. More than half of the bones uncovered in this region are from hadrosaurs. They’re among the dinosaurs that might have been on the decline well before the extinction.

We often see dinosaur skeletons plucked from their evolutionary context on display in a museum, a single page ripped from a book and taped to the wall. We’re impressed by their size, their odd forms, perhaps their ferociousness. There’s undoubtedly value in that. But knowing how they lived and understanding their rise and fall and what it means for the history of all life on earth requires a broader perspective. Here in southern Alberta, the dinosaurs remain part of a larger story still unraveling.