Want to See How an Artist Creates a Painting? There’s an App for That

The Repentir app reveals an artist’s creative process by allowing users to peel back layers of paint with the touch of their fingertips

![]()

The Repentir app reveals an artist’s creative process by allowing users to peel back layers of paint with the touch of their fingertips. Photo courtesy of Jonathan Hook. Artwork © Nathan Walsh

An artist’s studio is usually a private space, and the hours spent with a paint-dipped brush in hand mostly solitary. So, the final products we gaze at on gallery walls are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the makers’ creative processes.

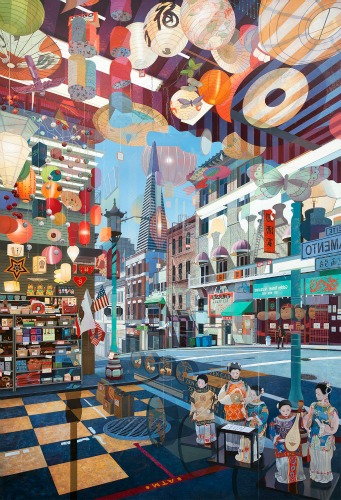

For Nathan Walsh, each of his realist paintings is a culmination of four months of eight to 10-hour days in the studio. Now, thanks to a new app, we can go back in time and see how his work came to be, stroke by stroke.

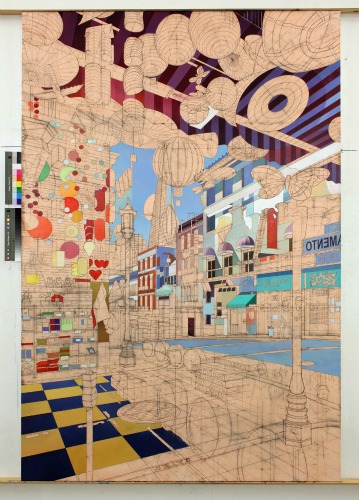

Repentir, a free app for smartphones and the iPad, provides a hand-controlled time-lapse of Walsh’s oil painting, Transamerica. It compresses months of sketching and revision into interactive pixels, allowing users to peel back layers of paint and deconstruct Transamerica to its original pencil sketches.

The app, developed by researchers at Newcastle and Northumbria universities in England, uses computer vision algorithms to recognize the painting in photographs taken from various perspectives. When you take a photo of any part of Transamerica (or the entire work), the app replaces your image with those captured in the studio as Walsh painted. Every day for four months, a digital camera set up in his York-based studio snapped a shot of his progress, accumulating roughly 90 images.

Researcher Jonathan Hook demonstrates how to use the Repentir app in front of Nathan Walsh’s Transamerica. Photo courtesy of Jonathan Hook. Artwork © Nathan Walsh

Users can view the painting’s layers in two ways. A slider feature at bottom allows viewers to see the piece in its beginning stages to the final product by swiping from left to right (think “slide to unlock”). They can also use their fingers to rub away at a given spot on the painting on the screen, revealing earlier stages in the process.

“Where their fingers have been, we basically remove pixels from the image and add pixels from older layers until they’re rubbed away,” says Jonathan Hook, a research associate at Newcastle who studies human-computer interaction. “It’s like how you add paint to the canvas—we’re doing the opposite.”

Repentir was unveiled this week at the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing in Paris, an annual science, engineering and design gathering. This year’s theme is “changing perspectives.” Transamerica will be on display there until tomorrow, when it moves to the Bernarducci Meisel Gallery, a realist painting collection in New York.

But you don’t have to visit the gallery to test out the app for yourself—you can pull up this print of the painting and snap a shot of your computer screen.

Realist painter Nathan Walsh drew inspiration from a visit to San Francisco’s Chinatown to create Transamerica, which took nearly four months to complete. © Nathan Walsh

The app relies on a process known as scale invariant feature matching, technology that’s similar to that of augmented reality. Researchers trained the app against a high-resolution image of Transamerica to identify and create markers for certain features. These markers can then be used to find matching features in a user’s photo of the painting and the artwork itself—even in a tiny piece of it.

“If you take a picture of the bottom right-hand corner, it will find the features in the bottom right-hand corner of the image and match them against those same features in the source image,” Hook says. “If there’s at least three or four features matched, you’re able to work out the perspective and the difference in image position on those features.”

Ninety images worth of layers may not sound like a lot when you factor in today’s smartphone scrolling speeds, but if you’re viewing Transamerica in person, there’s more than enough of it to explore. The canvas measures roughly 71 by 48 inches. It would take a massive number of screen grabs to rub away the layers of the entire work.

Transamerica is a colorful composite of elements that caught Walsh’s eye during a trip to San Francisco’s Chinatown, the largest Chinese community outside of Asia. Several years ago, Walsh traveled across America, stopping in major cities, including San Francisco, New York and Chicago, sketching and taking photographs of the urban landscapes.

Walsh spends about a month on sketching alone before he begins adding paint to the canvas. Here, Transamerica is in its beginning stages. © Nathan Walsh

Walsh says he’s often accused of stitching photographs together or touching up in Photoshop because of the realistic look of his paintings. He aims to convey a sense of three-dimensional space in his work. In Transamerica, the juxtaposition of different objects and designs create almost palpable layers of paint.

“There’s always an assumption that there’s some sort of trickery involved,” Walsh says. “Getting involved in a project like this explains literally how I go about constructing these paintings. It shows all the nuts and bolts of their making.”

Hook says the researchers chose Walsh’s work to expose those “nuts and bolts.” “Lots of people, when they see his paintings, they think he’s cheated, when in reality what Nathan does is just get a pencil and a ruler and draws these really amazing photorealistic pictures from scratch,” he says. “The idea behind the app was to reveal Nathan’s process and show people how much hard work he does.”

In this way, Walsh believes using Repentir in front of the actual work will make the gallery experience more educational for visitors. “For me, the exciting thing is that you’re getting close, as close as you can, to my experience of making the painting,” he says.

While the app is free, Hook believes the tool could lead to a new business model for artists. In the future, app users could purchase a print of a configuration of layers they like best.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marina-koren-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marina-koren-240.jpg)