What Animal Sounds Look Like

Mark Fischer, a software developer in California, turns data from recordings of whales, dolphins and birds into psychedelic art

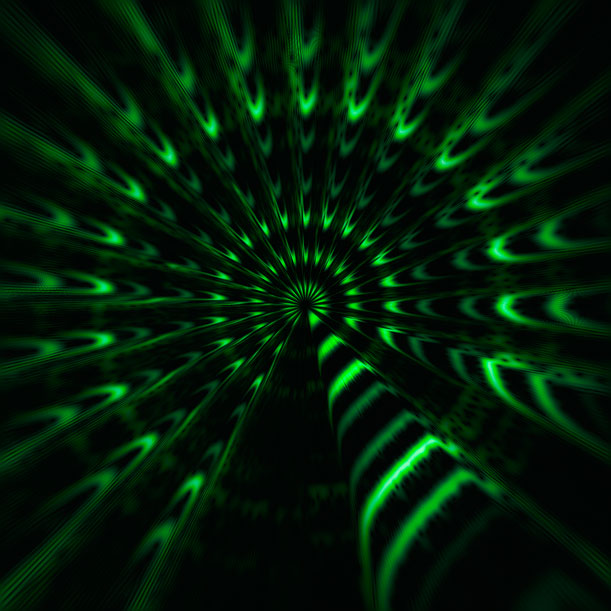

![]()

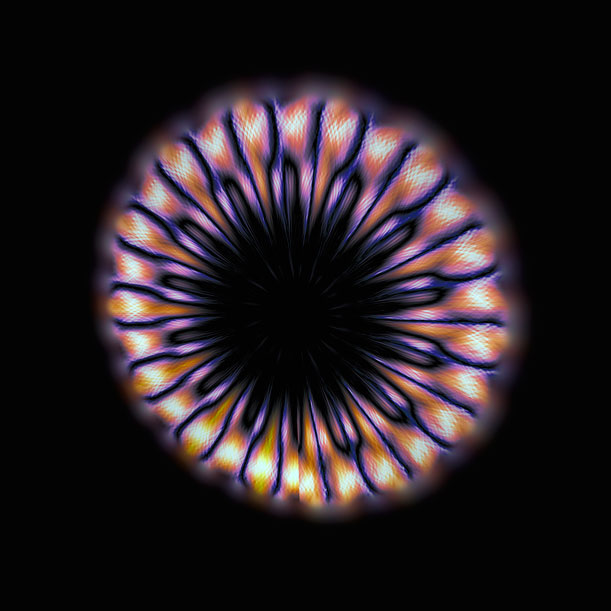

Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae). Image by Mark Fischer.

Those who have a neurological condition called chromesthesia associate certain colors with certain sounds. It’s these people that I think of when I see Mark Fischer’s Aguasonic Acoustics project. Fischer systematically transforms the songs of whales, dolphins and birds into brightly colored, psychedelic art.

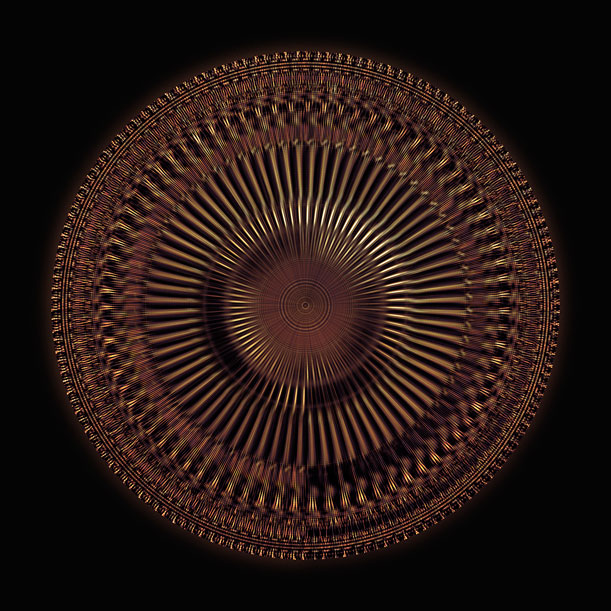

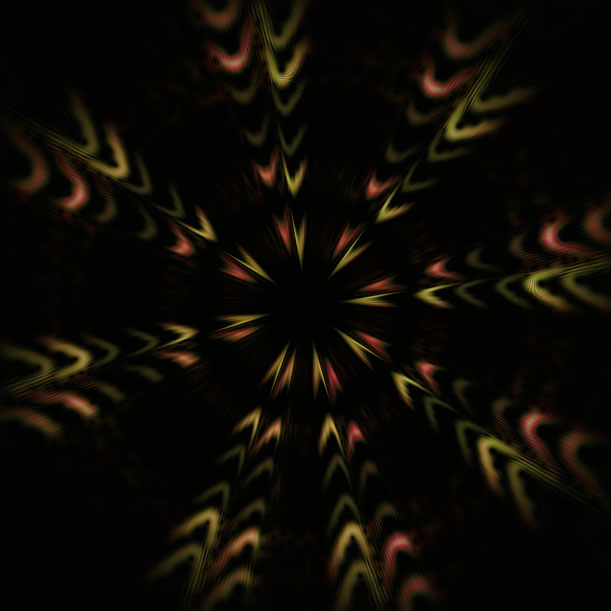

Minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata). Image by Mark Fischer.

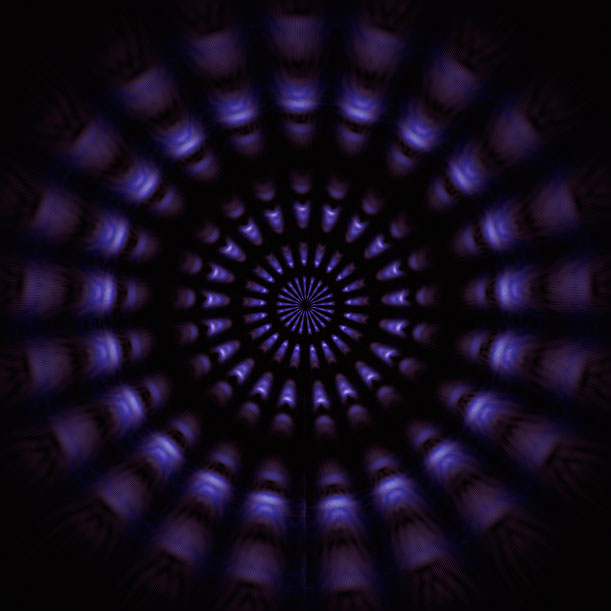

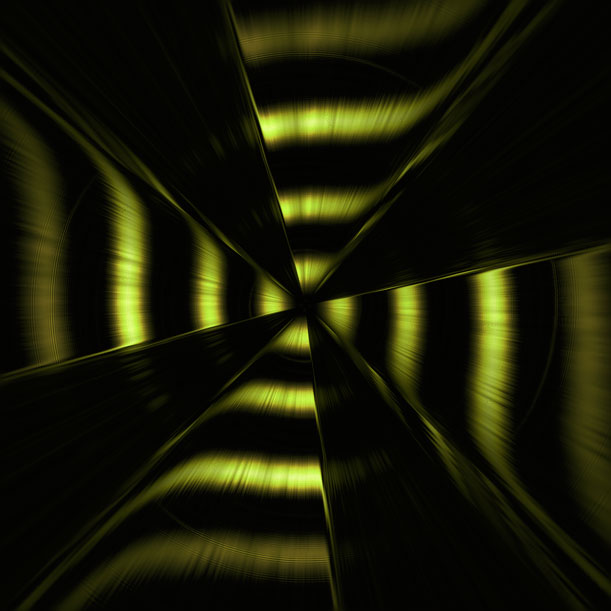

The software developer from San Jose, California, gathers the sounds of marine mammals in nearby Monterey Bay using a hydrophone and the chirps of birds in his neighborhood with a digital recorder; he also collects audio of other hard-to-reach species from scientists. Fischer scans the clips for calls that demonstrate a high degree of symmetry. Once he identifies a sound that interests him, he transforms it into a mathematical construct called a wavelet where the frequency of the sound is plotted over time. Fischer adds color to the wavelet—a graph with an x and y axis—using a hue saturation value map—a standard way for computer graphic designers to translate numbers into colors. Then, he uses software he personally wrote to spin the graph into a vibrant mandala.

“The data is still there, but it’s been made into something more compelling to look at,” wrote Wired.

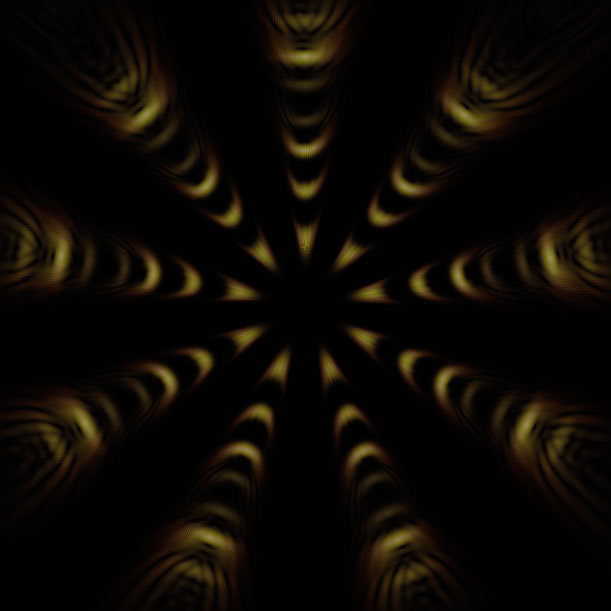

Vermiculated screech-owl (Otus guatemalae). Image by Mark Fischer.

The first animal sound that Fischer turned into visual art was that of a blue whale. “I was spending some time down in Baja California. Someone had posted a note on MARMAM looking for volunteers for a blue whale population survey out of the University of La Paz, and I volunteered. We spent the next three days in the Sea of Cortez looking for blue whales,” says Fischer. “We never did find a blue whale, but I was able to make recordings. I just got fascinated with the sounds of whales and dolphins.”

Rufous-tailed jacamar (Galbula ruficauda). Image by Mark Fischer.

Fischer concentrates on whales, dolphins and birds mostly, having found that their calls have the most structure. Humpback whales, in particular, are known to have incredible range. “They make very well defined sounds that have extraordinary shapes in wavelet space,” says the artist. The chirps of insects and frogs, however, make for less engaging visuals. When it comes to a cricket versus a humpback, Fischer adds, it is like comparing “someone who has never played a guitar in their life and a violin virtuoso.”

Rufous-tailed jacamar (Galbula ruficauda). Image by Mark Fischer.

Animal sounds have long been studied using spectrograms—sheets of data on the frequency of noises—but the software designer finds it curious that researchers only look at sounds this one way. Fischer finds wavelets much more compelling. He prints his images in large-scale format, measuring four feet by eight feet, to call attention to this other means of analyzing sound data.

Lesser ground-cuckoo (Morococcyx erythropygius). Image by Mark Fischer.

Some researchers argue that little progress has been made in understanding humpback whale songs. But, Fischer says, ”I am concluding that we are looking the wrong way.” The artist hopes that his mandalas will inspire scientists to look at bioacoustics anew. “Maybe something beneficial will happen as a result,” he says.

Short-eared owl (Asio flammeus). Image by Mark Fischer.

The Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, will include a selection of Fischer’s images in “Beyond Human,” an exhibition on artist-animal collaborations on view from October 19, 2013 to June 29, 2014.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)