What Genomic Research Can Tell Us About the Earth’s Biodiversity

Smithsonian scientists are gathering wildlife tissue samples from around the world to build the largest museum-based repository

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-tissue-sample-biorepository-631.jpg)

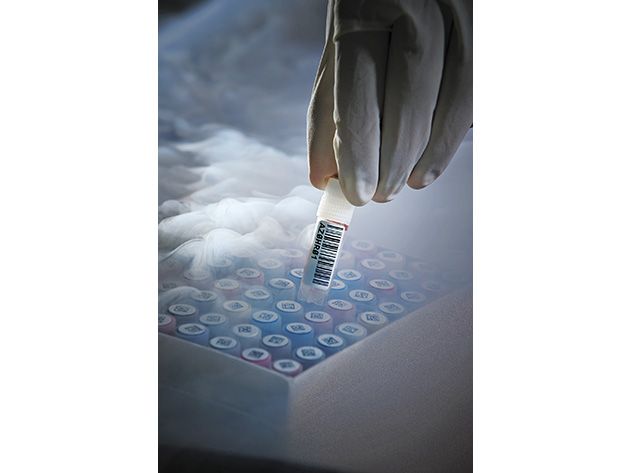

Inside two gleaming white rooms at a vast complex in a Maryland suburb of Washington, D.C. are 20 round five-foot-tall steel tanks whose contents are cooled by liquid nitrogen to temperatures as low as minus 310 degrees Fahrenheit. Lift the lid of one of the tanks and look through the wispy nitrogen vapor that wafts upward, and you’ll see rack upon rack of two-inch-tall plastic vials, tens of thousands of them, each containing a bit of tissue extracted from a living thing somewhere in the world—North American birds, Gabonese monkeys, venomous brown recluse spiders, Burmese rainforest plants, South Pacific corals.

There are now some 200,000 samples in the Natural History Museum’s new tissue collection, but that’s just the beginning. Researchers will be able to preserve some five million pill-size pieces of animals, plants, fungi, protists and bacteria in what will be the world’s largest museum-based biorepository—part of a multi-institution effort, called the Global Genome Initiative, to use genomic technology to understand and preserve earth’s biodiversity.

What the scientists are after is the genetic material in those samples, the DNA that holds the key to each species’ unique identity. “Genetic sequences can tell us how species have evolved over millennia,” says John Kress, a botanist who directs the Institution’s consortium for biodiversity knowledge and sustainability. “This collection is really going to transform the tool kit we have to understand nature.” An exhibition opening this month at the Natural History Museum, “Genome: Unlocking Life’s Code,” highlights the collection’s potential as well as scientific advances since the human genome was decoded ten years ago.

The museum, of course, has spent more than a century building a superlative specimen collection with millions of dried, stuffed and alcohol-preserved plants and animals. Those specimens remain invaluable but fall short in one respect: They’re not terribly useful for genetic sequencing because DNA degrades over time unless it is properly frozen. Yet, over the past 20 years, as new technologies enabled scientists to explore various species’ DNA, and as awareness of threats to wildlife increased, researchers grew more eager to analyze and conserve the living world’s genetic heritage. “We suddenly realized that there was a whole new type of collection we needed to preserve,” Kress says.

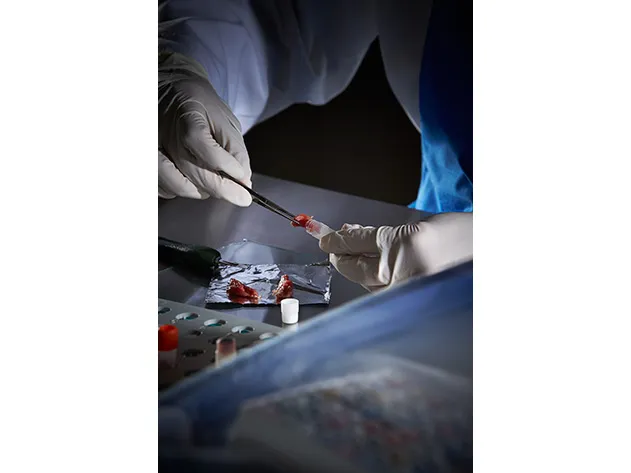

Now dozens of Smithsonian research teams are gathering tissue samples around the world. Marine zoologist Carole Baldwin leads a group that has already collected tissue from roughly 8,000 specimens, largely from Caribbean coral reefs. Each time a researcher finds a new species, he or she takes a tissue sample and puts it into a vial.

Those vials and others are frozen and shipped to the Maryland repository, where staff members remove a tiny piece of tissue for DNA barcoding, in which a segment of the organism’s DNA is sequenced to confirm which species the organism belongs to. That step alone has yielded surprises, differentiating species that look identical. “Scientists have studied shallow-water Caribbean fish diversity for 150 years,” Baldwin says. “But when we sampled just a tenth of a square mile area off of Curaçao and sequenced the specimens’ DNA, we found about 25 new fish species.”

Someday, after researchers determine a selected organism’s entire genome, they expect to gain a better understanding of its physiology and evolutionary history. What’s more, the tissue biorepository could function like a seed bank and preserve a species for posterity. Scientists speculate they might prevent an extinction by preserving living cell lines for future restoration. Beyond that are rescue missions that now have the ring of science fiction, such as reviving an extinct species. “It sounds like Jurassic Park,” Kress says, “but we shouldn’t discount the possibility.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)