What Happens to Fiction When Our Worst Climate Nightmares Start Coming True?

Movies, books and poetry have made predictions about a future that could be rapidly approaching

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2c/fb/2cfb49f6-c7af-43b5-b007-88ea6abbc36e/4838167533001_4911162625001_4911145572001-vs.jpg)

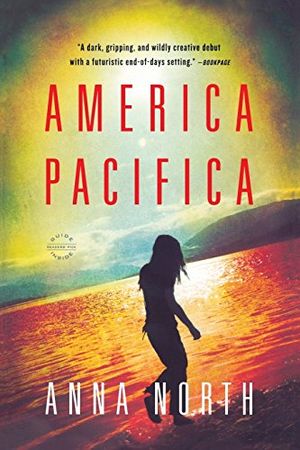

Fiction about the climate is ancient. After all, nothing lends itself to mythology like the swell and ebb of a river, a drought that kills the crops, a great flood that washes the land clean. But fiction about man-made climate change is newish, gaining attention as its own genre only in the last few years. I first heard the term “cli-fi” after the 2011 publication of my first novel, America Pacifica, in which an ice age destroys North America. At that time, the label, coined by the writer Dan Bloom, seemed obscure; today it is almost mainstream.

In my own writing, I thought of the end of the world as a crucible for my characters: What quicker way to make ordinary people into heroes and villains than to turn the weather against them and destroy everything they know?

Now the changes I once imagined are upon us. 2016 was the hottest year on record. Before that, it was 2015; before that, 2014. This year, 16 states had their hottest February on record, according to Climate Central. Arctic sea ice hit record lows this winter. Permafrost in Russia and Alaska is thawing, creating sinkholes that can swallow caribou. Meanwhile, President Trump has announced the United States will withdraw from the Paris agreement and intends to slash federal funding for climate research. Art that once felt like speculation seems more realistic every day.

Writing and movies about the apocalypse used to seem like exciting breaks from real life. As a writer, a dystopian setting was in part a way to avoid the mundane, to explore situations, problems and ideas outside the scope of everyday life. As a reader, I was both thrilled and disturbed by a world I barely recognized in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, a story that felt entirely new. When I saw Danny Boyle’s film Sunshine, I watched in rapture—how beautiful, the Sydney Opera House surrounded by snow.

A short cli-fi reading list would include Margaret Atwood’s "MaddAddam Trilogy" (Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood and MaddAddam), which is about genetic engineering gone mad in a time of environmental upheaval; Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife, a thriller that centers on water rights in Phoenix; Claire Vaye Watkins’s Gold Fame Citrus, a tale of refugees from a drought-parched California that feels all too familiar given recent weather patterns; plus Marcel Theroux’s Far North, Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior and Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140. For a film complement, watch Sunshine (about a dying sun, not carbon emissions, but similar in look and tone to other cli-fi stories), The Day After Tomorrow or the brilliant Mad Max: Fury Road, about a wasted desert ruled by the ruthless and physically decaying Immortan Joe, who controls all the water.

As a term, cli-fi is a little narrow for my taste, because some of the most interesting climate writing I know isn’t fiction. One of the most moving responses to our climate crisis is Zadie Smith’s essay “Elegy for a Country’s Seasons,” in which she enumerates the small pleasures already lost as climate change transfigures English weather: “Forcing the spike of an unlit firework into the cold, dry ground. Admiring the frost on the holly berries, en route to school. Taking a long, restorative walk on Boxing Day in the winter glare. Whole football pitches crunching underfoot.”

More fiery in its approach is the Dark Mountain manifesto, published in 2009 by two English writers, Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine, which describes climate change as just one of many pernicious effects of a cross-cultural belief in human supremacy and technological progress. The antidote, for Kingsnorth and Hine, is “uncivilization,” a way of thinking and living that privileges the wild over the urban and situates humans “as one strand of a web rather than as the first palanquin in a glorious procession.” The best way to spread this perspective, they argue, is through art, specifically writing that “sets out to tug our attention away from ourselves and turn it outwards; to uncentre our minds.”

Kingsnorth and Hine mention the 20th-century poet Robinson Jeffers as a prime example of this kind of writing. Early in his career, the poet “was respected for the alternative he offered to the Modernist juggernaut,” they write. But it’s a Modernist poet I think of when trying to trace the roots of climate fiction, or at least my relationship with the genre: T.S. Eliot.

Eliot’s seminal poem “The Waste Land” anticipates human-caused climate change, especially in the final section that draws on the legend of the Fisher King, his lands laid waste by his impotence. It’s here we get “rock and no water and the sandy road,” the “dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit,” the “dry sterile thunder without rain.” Eliot was not worrying about climate change—England’s climate was not yet changing noticeably in 1922 when the poem was published. But humans are not so different now from a hundred years ago. Drought has always brought despair, and thunder fear, and unusual weather a creeping sense that the world is out of joint. “The Waste Land” just seems more literal now.

Now that Eliot’s “dead mountain mouth” reads like a description of last year in California, and his “bats with baby faces in the violet light” feel like they might be right around the corner, is climate fiction going to rouse humans to action?

J. K. Ullrich in The Atlantic cites a study showing that people felt more concerned about climate change and more motivated to do something about it after watching the climate disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow. But fiction is, at best, an inefficient means of instigating political action—will the desiccated Los Angeles of Gold Fame Citrus, for instance, spur readers to conserve water, or just make them pour themselves a tall, cool glass before it’s all gone? Will the weird, lonely land of Oryx and Crake, full of genetically engineered animals and children, and almost devoid of ordinary humans, encourage support for renewable resources or only make readers lie down in despair? And will those most skeptical of climate change ever pick up a volume of climate fiction in the first place?

The primary function of climate fiction is not to convince us to do something about climate change—that remains a job primarily for activists, scientists and politicians. Rather, fiction can help us learn how to live in a world increasingly altered by our actions—and to imagine new ways of living that might reduce the harm we do. In Gold Fame Citrus, the dune sea essentially creates its own culture, its mysterious pull (whether physical, metaphysical or merely psychological is not entirely clear) collecting a band of outcasts with a charismatic leader who makes of desert life a kind of new religion. In Mad Max: Fury Road, a handful of female rebels, led by the heroic Imperator Furiosa, kill Immortan Joe and take over his water supply.

Neither is exactly a hopeful story. Levi Zabriskie, the desert cult leader in Gold Fame Citrus, is a liar and a manipulator, and the fate of his followers remains uncertain at the end of the novel. The conclusion of Fury Road is more triumphant, but even the benevolent Furiosa will have to rule over a blasted country, where her fabled “green place” has become a dark mudscape traversed by creepy beings on stilts. What the best of climate fiction offers is not reassurance but examples, stories of people continuing to live once life as we know it is over. Post-apocalyptic fiction takes place, by definition, after the worst has already happened; the apocalypse is the beginning, not the end, of the story.

There’s still time, I hope, to avert the worst of climate fiction’s nightmares. But even if we don’t find ourselves lost in the sand dunes in our lifetimes, we will surely need to rethink the way we live, perhaps radically so. I don’t know if I agree with Kingsnorth and Hine that we will have to become “uncivilized.” But we will have to change what civilization means. Some of these changes may be painful. Many will feel strange. As we make them, it is useful to be told that humans could live on a sand dune, in a wasteland, in a spaceship aimed at the sun. It might behoove us to make some modifications now, before we are forced into much more drastic transformations.

I wrote America Pacifica because I wanted to imagine a time when humans would be morally tested, when dire circumstances would make heroes or villains of us all. Now that time has come: We are being tested, every day. I, along with many readers, look to fiction to find ways we might pass that test.