What Happens to a Town’s Cultural Identity as Its Namesake Glacier Melts?

As the Comox Glacier vanishes, the people of Vancouver Island are facing hard questions about what its loss means for their way of life

:focal(976x1154:977x1155)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/29/e629548c-e895-4ce0-8976-f5c954011432/courtenay-vi-glaciers.jpg)

This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

In most weather, you would never know that the Comox Glacier loomed above the town, except that you still would. You’d notice the Glacier View Lodge. The Glacier Greens Golf Course. Glacier View Drive. Glacier Environmental handles hazardous materials, Glacier-View Investigative Services offers discreet PI work, the junior hockey team is called the Glacier Kings. Because the glacier is also known as Queneesh in the local indigenous language, there’s Queneesh Road, Queneesh Mobile Home Park, Queneesh Elementary School.

You have begun to picture a classic mountain town. Not so. The town, which is really a tri-city mash-up of Courtenay, Comox, and Cumberland on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, is distinctly coastal—more gumboots than ski boots, with the big, gloom-green trees that suggest heavy rainfall. A swimming pool the depth of the average annual precipitation would come up to your nipples. As a local visitors’ guide deadpans, “The winter months can be quite humid.”

Yet the Comox Valley, as the mash-up is often called, has ice on the mind. Up a thousand meters in the Beaufort Range, the torrents of rain have historically fallen as snow, fattening glaciers that drape whitely across the ridgelines like cats on the crest of a chesterfield. The Comox Glacier is the greatest among them. On clear days, it’s visible from almost anywhere in the valley.

Science predicts that the Comox Glacier is vanishing, but Fred Fern knows it is. A retired millworker with all the plainspoken aversion to show-offyness that that suggests, Fern has lived in the Comox Valley for more than 40 years. Lately, he’s made a hobby of photographically cataloging Vancouver Island locations as they change with the changing climate. His collection of images now numbers more than 20,000, mainly of estuaries where he believes he is witnessing sea-level rise.

But his most dramatic photos are of the Comox Glacier, in part because he only turned his attention to it in 2013. In just three annual portraits since, the ice cap is visibly ever more bluely crevassed, giving way on all sides to clay-colored bedrock.

“The glacier means a lot to me,” Fern says, sitting in the great Canadian muster station that is a Tim Hortons doughnut shop. “My family left when I was 18 to go back east, because my dad got posted there, and I decided to stay. And one of the reasons was that glacier. I’d been around the world—I’d never seen a place like Comox. Just a beautiful, unbelievable place.”

Fern is the type whose force of feeling shows in a wry smile, a sheltering cynicism. But the sense of mourning he expresses is palpable. In 2003, the Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht termed this solastalgia. Albrecht had noticed psychological and even physical symptoms of distress among people in the Upper Hunter Valley of eastern Australia, where more than 15 percent of the landscape had been stripped by open-pit coal mining in the course of just two decades. The comfort—the solace—that the locals had derived from a place they knew and loved was being taken from them. They were, Albrecht said, “homesick without leaving home.”

The Comox Valley is in the Pacific coastal temperate rainforest zone, an interface of earth and water that stretches from northern California to Kodiak Island in southeastern Alaska. Here, glaciers at low altitude tend to be relatively small and vulnerable to milder temperatures. Still, fully 16 percent of the region is ice covered, and it is remarkably ice affected. Rivers fed only by rain and snow tend to spike in spring and fall. Ice field-to-ocean rivers are different, maintaining a steadier, cooler flow of summer glacial meltwater that supports the region’s seven species of salmon as well as other cold-water fish. With rock-grinding glaciers at their headwaters, these rivers are also nutrient rich, feeding downstream species from alpine plants to Pacific plankton. The sheer volume of the annual runoff boggles the mind: roughly equivalent to the discharge of the Mississippi River. It’s higher than ever these days, of course. The region is losing glacial ice faster than almost any other place on Earth.

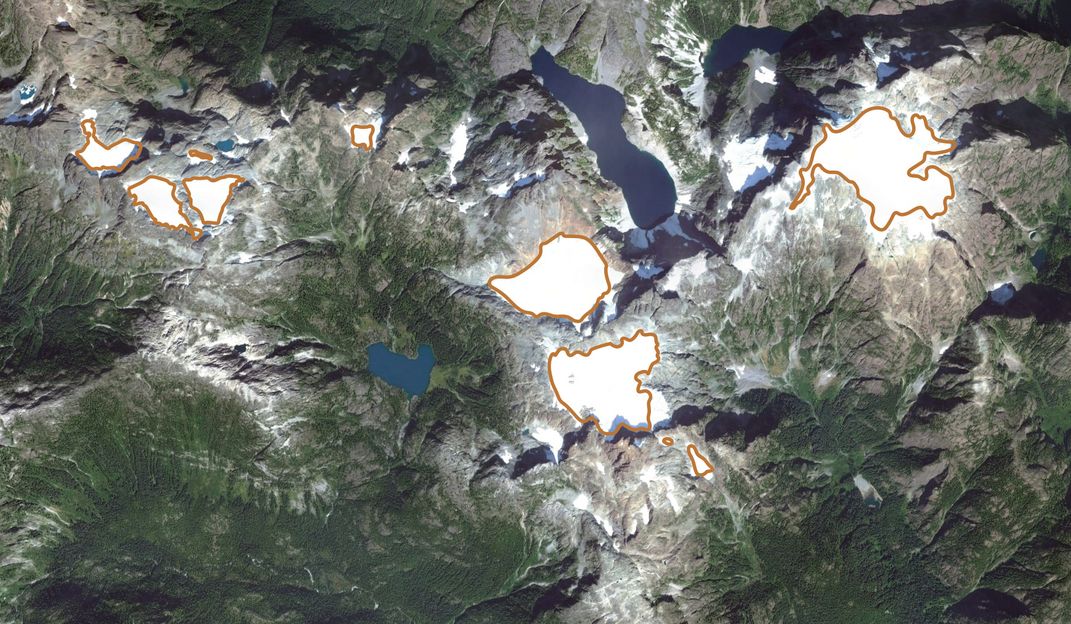

Most of the coast’s glaciers are rarely seen, either remote from cities and towns or hidden from view in the mountains. Pop up in a twin-engine Piper Navajo aircraft, however, as I did on a bluebird day in early autumn, and a world of ice is suddenly revealed. There are glaciers everywhere, some huge, but more of them tucked away in alpine saddles and basins, looking like nothing so much as bars of old soap: pitted and plasticky and antiseptic blue.

“If you want to see them, see them now,” says Brian Menounos, a glaciologist with the University of Northern British Columbia and leader of the project I joined in the aircraft. Menounos is surveying coastal glaciers in western North America using lidar, a detection system that measures the distance from an overhead aircraft to a glacier’s surface by firing a laser up to 380,000 times per second, then capturing its light-speed bounceback in a mirror. (The project is funded by the Hakai Institute, which supports coastal science in British Columbia. The Hakai Institute and Hakai Magazine are separate and independent agencies of the Tula Foundation.) Crisscrossing an ice field, researchers capture data points that can be used to create images representing the height and area of a glacier to within centimeters. One lidar pilot told me that the pictures can be so fine grained that, in one, he could tell a man was wearing a cowboy hat.

The lidar survey, when compared to past air and satellite imagery, will give a more precise sense of what is happening to British Columbia’s coastal glaciers, and set a baseline against which to measure changes in the future. Already, glaciers across the province are known to be losing thickness at an average rate of about 75 centimeters of meltwater per year. That means more than 20 cubic kilometers of ice are disappearing across British Columbia annually. In global perspective, that volume of ice is like losing one of the larger Himalayan glaciers every year—Gangotri Glacier in India, for example, one of the sources of the fabled Ganges River.

In on-the-ground reality, most of the ice that British Columbia is losing is vanishing from the coast, where the rate of glacier loss has doubled in recent years. Menounos’s favorite ice field, for example, is Klinaklini Glacier, only 300 kilometers northwest of Vancouver, but unknown to most of the city’s residents. Even on Google Maps, the glacier stands out as a vaguely fallopian blue-white confluence that flows from high peaks nearly to sea level. “I haven’t been on it,” Menounos says, “but when you fly over it in a floatplane, you’re just in awe with the sheer size.” Klinaklini, which is up to 600 meters thick in places, has thinned by an average of 40 meters since 1949. As the glacier has receded, areas of ice more than 300 meters tall—that’s 1,000 feet—have completely melted away.

Menounos says he would be surprised if Vancouver Island—the largest island on the west coast of North America, and currently polka-dotted with what is marked on maps as “permanent snow and ice”—still had glaciers beyond 2060. If you find that hard to believe, consider the fact that what is now Glacier National Park, just stateside across the Canada-US border in the Rocky Mountains, had 150 glaciers in the mid-1800s and has 25 today. In 2003, scientists predicted the park would have no permanent ice by 2030; the same scientists later said that the ice could vanish in the next five years.

Menounos is a big-picture guy. He can tell you that, in the hot, dry summer of 2015 alone, Vancouver Island’s glaciers thinned by more than three meters, but he can’t know every one of those ice fields intimately. For that, you need people like Fred Fern, who estimates that the Comox Glacier will be gone in five years if the current weather patterns hold. If Fern is right, then nothing that the rest of us can do, no shift to electric cars or treaty signed by world leaders, will solve climate change quickly enough to save it.

“I’m sure that if instead of 75 years, we lived 500 years, we wouldn’t be doing what we’re doing now,” says Fern. “Because then you got the memory, and plus you’re like, man, we’d better not wreck things, because when I’m 365 …” His voice trails off, and then he laughs, a little dryly.

To live for 500 years: a person can’t do it, but a culture can. In his shore-front house on the K’ómoks First Nation reserve, Andy Everson says he can’t remember when he first knew the Comox Glacier by its older name, Queneesh. He supposes he learned the story from his mother, who learned it from her mother, and so on.

In the version that Everson tells, an old chief is forewarned by the Creator to prepare four canoes for a coming flood. The floodwaters ultimately cover the land completely, leaving the people in the canoes adrift until they’re able to fasten ropes to a giant white whale: Queneesh. At last, as the waters begin to recede, the whale beaches itself on the mountains, and is transformed into a glacier.

Most people in the Comox Valley know the Queneesh narrative, with its curious resonance to the biblical story of Noah. One detail from Everson’s telling, however, is often left out: Queneesh didn’t just save the K’ómoks—it anchored them in place. “You almost can consider this an origin story,” Everson says.

Everson has immersed himself in his ancestors’ traditions, but he’s also a thoroughly of-the-moment 43-year-old, with a master’s degree in anthropology and a fondness for time-trial cycling. He’s well known as a printmaking artist, most famous for his portraits of Star Wars characters in a contemporary Northwest Coast style. Yet his very first limited-edition print featured Queneesh, and he has returned to the theme again and again.

“People come here, they see eagles spiraling in the sky with the glacier in the background, and decide to move here,” he says. It’s a scene I had witnessed that morning with my own eyes, and Everson once featured it in a print called Guided Home. But many of these newcomers, he says, don’t stay for long, or if they do, their children typically leave. “They’re like nomads. But we stay put. We’ve been here for thousands of years.”

Glaciers have been a part of this coast from time immemorial. Modern science and traditional narratives tell an increasingly similar story of this place, remembering a colorless, mercurial world of ice that slowly gave way to a land filled with life. Flood stories like the legend of Queneesh are widespread on the BC coast, and the geological record, too, is marked with the devastating floods that accompanied the great melt at the end of the Ice Age. There are harrowing tales of heroes who paddled their canoes through tunnels in the glaciers, risking their lives in hopes of finding greener pastures on the other side. There are stories that recall the arrival of salmon in streams and rivers newly released from the grip of the Ice Age.

“The modern preconceived notion of mountains as inhospitable places which people have avoided is wrong,” writes archaeologist Rudy Reimer in his thesis paper. Reimer hails from Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw, or the Squamish Nation, and works out of Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. “The world above the trees,” as Reimer calls it, was busy, at least in some seasons, with people picking berries, making tools, hunting, perhaps taking journeys of the spirit. Some glaciers were important routes from the coast to the interior, a fact made tangible in 1999, when hunters discovered the 550-year-old remains of an indigenous traveler, now known in the Southern Tutchone language as Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi, or Long Ago Person Found, melting out of glacial ice in a mountain pass.

But these are mere practicalities. The critical fact is that glaciers were, and to varying degrees still are, seen in First Nations’ cosmologies as beings, just as Queneesh is in the K’ómoks story. As anthropologist Julie Cruikshank writes in Do Glaciers Listen?, “Their oral traditions frame glaciers as intensely social spaces where human behavior, especially casual hubris or arrogance, can trigger dramatic and unpleasant consequences in the physical world.”

The term “social,” as applied to our relationship with nature, may strike you as misplaced—as though we could friend a squirrel on Facebook or do brunch with a coral reef. I’ve made sense of it, though, through a glacier story of my own.

For years when I was a child, my family made annual trips to the Illecillewaet Glacier in Glacier National Park (there are parks of this name in both the United States and Canada; the one I’m referring to here is in eastern British Columbia). We would hike up, then eat lunch at the toe of gray ice and drink water from a tarn—a glacier-fed pool—there. The tradition faded, but years later, I made my own return. I didn’t find the glacier, though—not as I remembered it, anyway. It had shrunken up the mountainside to a new and unfamiliar position, and there was no frigid pool at its toe. I realized then that the glacier had been an important companion on those family trips, a literal éminence grise around which we would gather. I had developed a social relationship with the ice field, and in its diminishment I felt the diminishment of myself. I felt solastalgia.

Many of the First Nations people Cruikshank met with in northern BC told her about an ancient taboo against burning fat or grease in the presence of a glacier. She speculates that this prohibition may have origins in the fact that animal tallow resembles a glacier in miniature: a solid white mass that melts when heated. But Cruikshank also acknowledges that the academic urge to “figure things out” could get in the way of more important insights, such as the way that such traditions keep glaciers in mind and entangle human behavior in their fates. Is it absurd to point out that the “casual hubris and arrogance” Cruikshank spoke of has surely played a role in the melting of glaciers today? Can we see nothing but coincidence in the fact that we have caused the melting by burning oil?

The degree to which you yawn about melting glaciers varies with the closeness of your social relationship to them. Fred Fern cares a lot. So does Andy Everson. It’s one thing to read about Greenland in the news, or to lose some lovely part of the local scenery. It’s quite another to lose your spiritual anchor or a lodestone of your identity. “People in the community are wondering what it means if the glacier goes,” Everson says. “If there is no glacier, is it still Queneesh?”

Strangely (or again, maybe not, depending on your perspective), glaciers are coming to life, just now, in their twilight hours. For years, the predominant view has been that they are not only lifeless, but hostile to life. Even environmentalists have bemoaned the protection of so much “rock and ice” in parks, rather than such biologically rich landscapes as rainforests or grasslands. Only recently have we thought of alpine ice as an endangered ecosystem in its own right.

The first review of what we know about how mammals and birds use glaciers was published only last year, by Jørgen Rosvold, a researcher with the Norwegian University of Science and Technology Museum. He found mainly that we don’t know much. (What on earth, for example, were wild dogs and leopards doing on the ice of Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya in Africa, where their carcasses have melted out of glaciers?) He nonetheless described a world that is very much alive.

American pikas, cataclysmically cute puffballs that are highly sensitive to warming temperatures, make cool burrows along glacier edges. Birds such as snow buntings, horned larks, and alpine accentors forage for windblown insects on ice fields. Mountain sheep, mountain goats, muskoxen, and the like, all built for the cold, retreat onto snow and ice for relief from heat and biting bugs. This is no minor matter: in 1997, a biologist in southwestern Yukon discovered a carpet of caribou droppings a meter and a half deep and the length of a football field melting out of a glacier. The dung had accumulated over at least 8,000 years.

Wolverines refrigerate kills in summer snow patches. Spiders prowl on glaciers, bears play on them, moss grows on them. More than 5,000 meters into the thin air of the Andes, the white-winged diuca finch weaves cozy nests of grass amid the aqua icicles of glacial cavities; this was the first known example of any bird other than a penguin regularly nesting on glacial ice, and it was first recorded just 10 years ago.

Glaciers have now been described as “biologically vibrant” by one researcher. The presence of glaciers appears to increase the biodiversity of mountain landscapes, because they add their own specially adapted species to the overall richness of life. Remove glaciers from a watershed, for example, and the number of aquatic insect species may drop by as much as 40 percent. Rutgers University biologist David Ehrenfeld has called these cold-spot ecologies, “an evolutionary pinnacle of a different sort, nature fully equal to the terrible rigors of a harsh climate.” Yet each of these observations dates from the 21st century. Science is granting life to glaciers just in time for them to die.

If the Pacific temperate rainforest loses its ice, water flows will change from the steady flow of summer meltwater to flashing spikes of rain in the spring and fall. The wash of finely ground minerals from the mountains, the “glacial flour” that turns rivers milky, that gives glacier-fed lakes their celestial blue, will slow. The yearly runoff of frigid freshwater that enters the sea will wane, possibly causing shifts in coastal currents. Some salmon species may benefit, scientists say; others may suffer declines. But the end of glaciers will not be the end of the world, only the end of the ice world.

This is as true of culture as it is of nature. On my last day in Comox, I meet Lindsay Elms, a local alpinist and mountain historian. Elms moved to Vancouver Island in 1988, and for years spent some 120 days each year in the backcountry as a guide. He now works at Comox Valley’s hospital, but still spends three months’ worth of days each year in the island alpine.

Many of us have begun to notice the effects of climate change, but Elms already lives in a different world. He’s seen glaciers break down into dirty, jumbled blocks. He’s felt the time it takes to reach mountain ice from his campsites quadruple in some cases. He now stands on frost-free summits in December, climbs peaks in midwinter that were once guarded by days of slogging through heavy snow. “But people adapt,” he says. “You can still have that wilderness experience.”

Elms has visited the Comox Glacier dozens of times. The last he heard, from a mountaineer friend, there was a lake forming on the plateau where there used to be ice. It’s a quirk of local history, Elms says, that the mountain on which the Comox Glacier stands is nameless—it’s just called the Comox Glacier. He finds himself asking much the same question as Andy Everson: what do you call the Comox Glacier when there is no glacier on it? It’s a question that Elms thinks only the K’ómoks can answer. Still, he has his opinion.

“I think it has to be Queneesh,” he says. “It’s got to be Queneesh.”

Calling the ice-free mountain by the name of its lost glacier would be a reminder to keep the natural world close, to remember to care. You could see it as recognition that Queneesh will always be present, in spirit at least. Or you could see it as a name on a tombstone.

Read more coastal science stories at hakaimagazine.com.