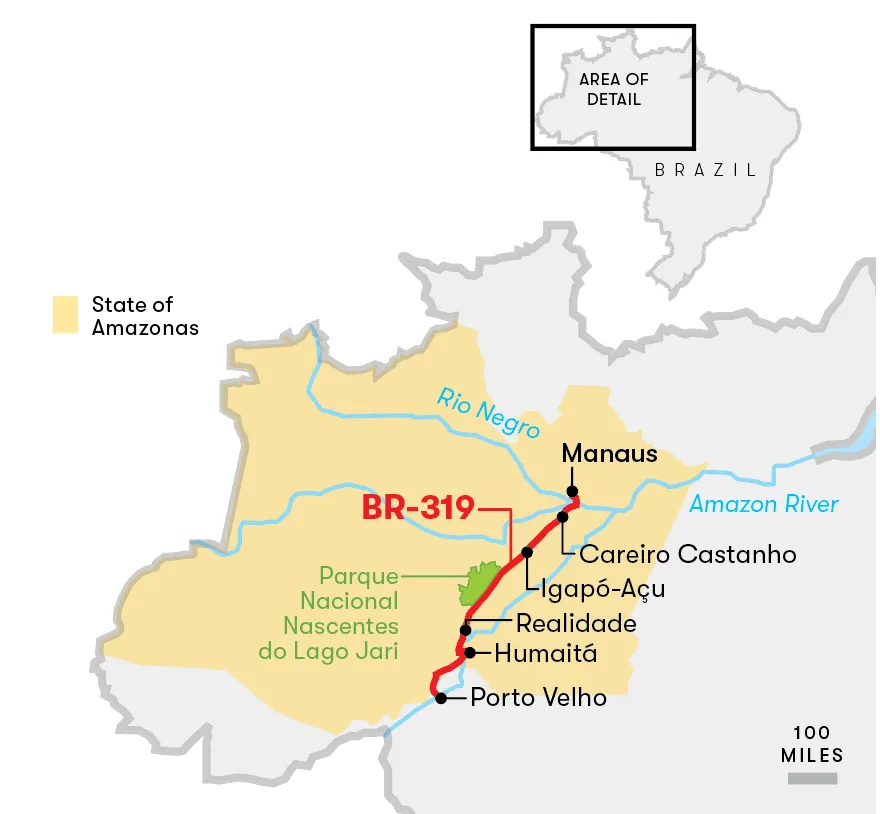

We loaded the car onto the ferry in Manaus, Brazil, a city of two million people rising from the jungle where the Rio Negro flows into the Amazon River, a confluence as seemingly wide and wild as the ocean. The boat took us across the great bay, past stilted huts, floating docks and flooded forest. After more than an hour, we reached the terminus, on the south bank of the Amazon. We disembarked at a town of low-slung cinder-block markets and houses with corrugated roofs. It was here that we began our real journey, a drive of several hundred miles down a rutted, frequently washed out, largely unpaved highway known as BR-319. The road plays a surprising role in the health of the Amazon rainforest, which, in turn, affects the composition of Earth’s atmosphere and therefore the air we breathe and the climate our descendants will experience, wherever on the planet they happen to live.

BR-319 was first built in the 1970s by Brazil’s military dictatorship, which viewed the rainforest as terra nullius—a no-man’s land waiting to be developed. Not long before, the government had established a free-trade zone in Manaus, and Harley-Davidson, Kawasaki and Honda soon built factories there. BR-319 connected Manaus to Porto Velho, 570 miles to the southwest, and thus to São Paolo and beyond. But when the military regime abdicated, in the 1980s, Brazil’s young democratic government lost interest in BR-319, and after years of neglect much of the route had become virtually impassable.

That was fortunate, according to many scientists and conservationists: It limited industrial logging and forest-clearing in the region. As roads go, BR-319 is especially significant because it traverses a vast unspoiled region, says Philip Fearnside, an American ecologist based at Manaus’ National Institute of Amazonian Research, or INPA. “It runs into the heart of the Amazon,” he says. “What protects the forest best is its being inaccessible.”

Ecologists are concerned because trees and other vegetation in the Amazon rainforest remove as many as two billion tons of atmospheric carbon each year—acting as an important brake on global warming, and helping to replenish the atmosphere with oxygen.

Fearnside warns of a “tipping point,” a threshold of deforestation that, if crossed, will doom the ecosystem. Today, 15 to 17 percent of the rainforest has been wiped out. Once 20 to 25 percent is gone, experts say, more and more rainforest will turn into savanna, and that change will bring longer dry seasons, hotter temperatures, more fires and less rain. “The Amazon will go from CO2-storing to CO2-emitting,” Fearnside says, with dire global consequences.

So far, most of the deforestation in Brazil—up to 95 percent—has taken place within 3.5 miles of a road. Which is why environmental advocates and others were alarmed this past July when Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro announced plans to rebuild BR-319 in order to spur economic development. Between August 2018 and July 2019, nearly 3,800 square miles of the Brazilian Amazon were destroyed, a 30 percent increase over the previous year—signifying a dramatic upward trend after years of declining rates, which ecologists attribute to environmental deregulation under Bolsonaro.

In July, I came to the Brazilian state of Amazonas to drive the long-abandoned road. For 90 miles south of the port town of Careiro da Várzea, BR-319 is paved, but soon it becomes a dirt track. With a guide, João Araújo de Souza, an indigenous Amazonian who grew up 25 miles south of Manaus, we set off through the forest. De Souza, who works as a technician at INPA, has driven BR-319 many times. We crossed bridges of rough-hewn planks and rivers of black water, stained dark like tea by decaying vegetation. Such black water, de Souza explains, is a good sign—no malaria, because the larvae of disease-bearing mosquitoes can’t survive in such highly acidic water.

In a town called Careiro Castanho, 90 miles from Manaus, we pass the last gas station for hundreds of miles. Another few hours and we reach a reserve known as Igapó-Açu—a “green barrier” spanning almost a million acres of forest, enveloping BR-319. This “sustainable development reserve” was established in 2009 to protect the forest and the 200 indigenous families who live here. They are allowed to cut trees, but only for their own needs. For income, they run a ferry across the Igapó-Açu River, a tributary of the Madeira River.

We meet Emerson dos Santos, 41, a round-faced, heavyset man, and his 15-year-old daughter, Érica, who comes running with a wriggling fish in her hands. “The best fishing in the world!” says dos Santos, who built guesthouses on the river and dreams of sustainable tourism in Igapó-Açu. But for that he needs guests, he says, and guests need a good road. Like all the residents we met, dos Santos was ambivalent about BR-319. He wants it to be rebuilt—for ambulances and police, for tourists—but he does not want the road to bring industrial mining and logging operations. In de Souza’s words, dos Santos wants to “suck on sugar cane and at the same time to smoke it.”

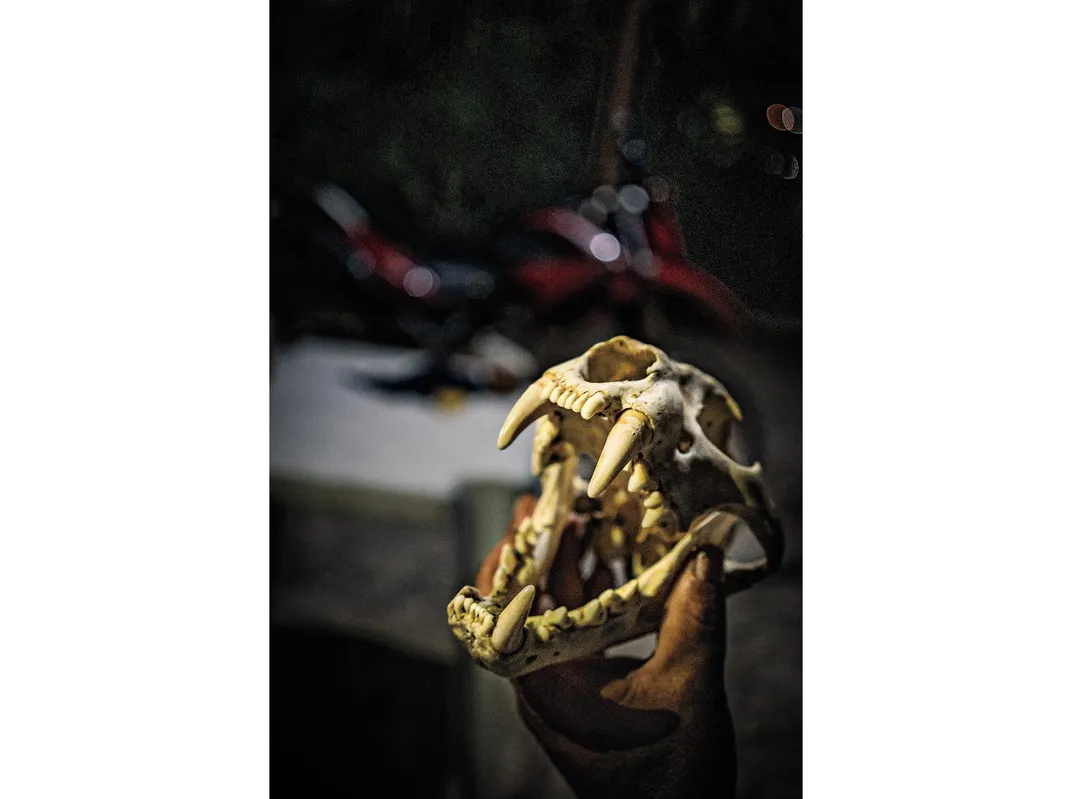

We set off again, and at Mile 215 we cross a bridge over Buraco da Cobra, the Snake Pit, where the skeleton of a truck lies in the bed of a creek below. It’s said that the driver was never found—only his half-eaten backpack. At Mile 233 is Toca da Onça, the Wildcats’ Lair. Motorcyclists go missing here, ambushed by panthers. Before long, we enter Nascentes do Lago Jari National Park, one of the world’s most biodiverse forests. As many as 1,000 tree species can be found in one square kilometer, roughly the same number of species as can be found in the entire United States. Capuchin monkeys jump from tree to tree as we pass through.

At 300 miles, the ground becomes firmer, the potholes fewer; someone has been fixing them up. An excavator, like that used at a construction site, appears as if out of the undergrowth. We see a narrow corridor gouged into the forest. “That wasn’t there two weeks ago,” says de Souza. Within a few miles we see dozens more corridors. Tree trunks are piled on cleared forest grounds. Farmland appears on the edge of the road, then cattle and stables. Signs claiming “private property” stand along the road, even though that is not possible: We are in a national park.

Realidade, a town first settled in the 1970s, has become a logging boomtown in the past five years. Yet most of the logging here is illegal—the land falls under the protection of Brazil’s “forest code,” which in recent years has tightly restricted private land use in the Amazon. We’re told that investors are buying up huge tracts, and pay loggers 100 reais per day—the equivalent of $25. Tractor-trailers, excavators and other heavy machinery followed, which are used to pull down trees. Eight sawmills have opened. Some 7,000 people are now living in this illicit frontier town.

At a small hotel, we meet a tired, warmhearted 50-year-old named Seu Demir. When he arrived here “at the end of the world,” he says, there were only a few houses. People gathered Brazil nuts and sold them in Humaitá, a city to the south. Demir bought a piece of land for the cost of a meal and founded the inn. Two years ago, he acquired more land, 60 miles to the north—some 2,000 acres in Lago Jari. The land lies within protected forest, less than seven miles from BR-319. Using machinery provided by investors in São Paulo he is now opening a corridor. Among the most valuable trees on “his” property are itaúba, a precious wood for shipbuilding, cedrinho, for homes, and angelim, for furniture. Some of the trees are more than 800 years old.

Isso é realidade, I thought. This is reality.

Editor's Note: Translated from German by Elias Quijada. A version of this article appeared in the Swiss weekly Das Magazin.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/0c/6f0cdf78-729d-4367-b98f-6a1adb0629b1/mobileamazonhighway.jpg)

:focal(2367x1230:2368x1231)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/f9/09f9e172-e93c-4691-b286-5ffe632f72b2/openeramazonhighway.jpg)