What’s Really Changed—and What Hasn’t—About Getting Humans to the Moon

NASA’s Orion will combine vintage tech with massive advances in computing power and electronics we’ve made since 1972

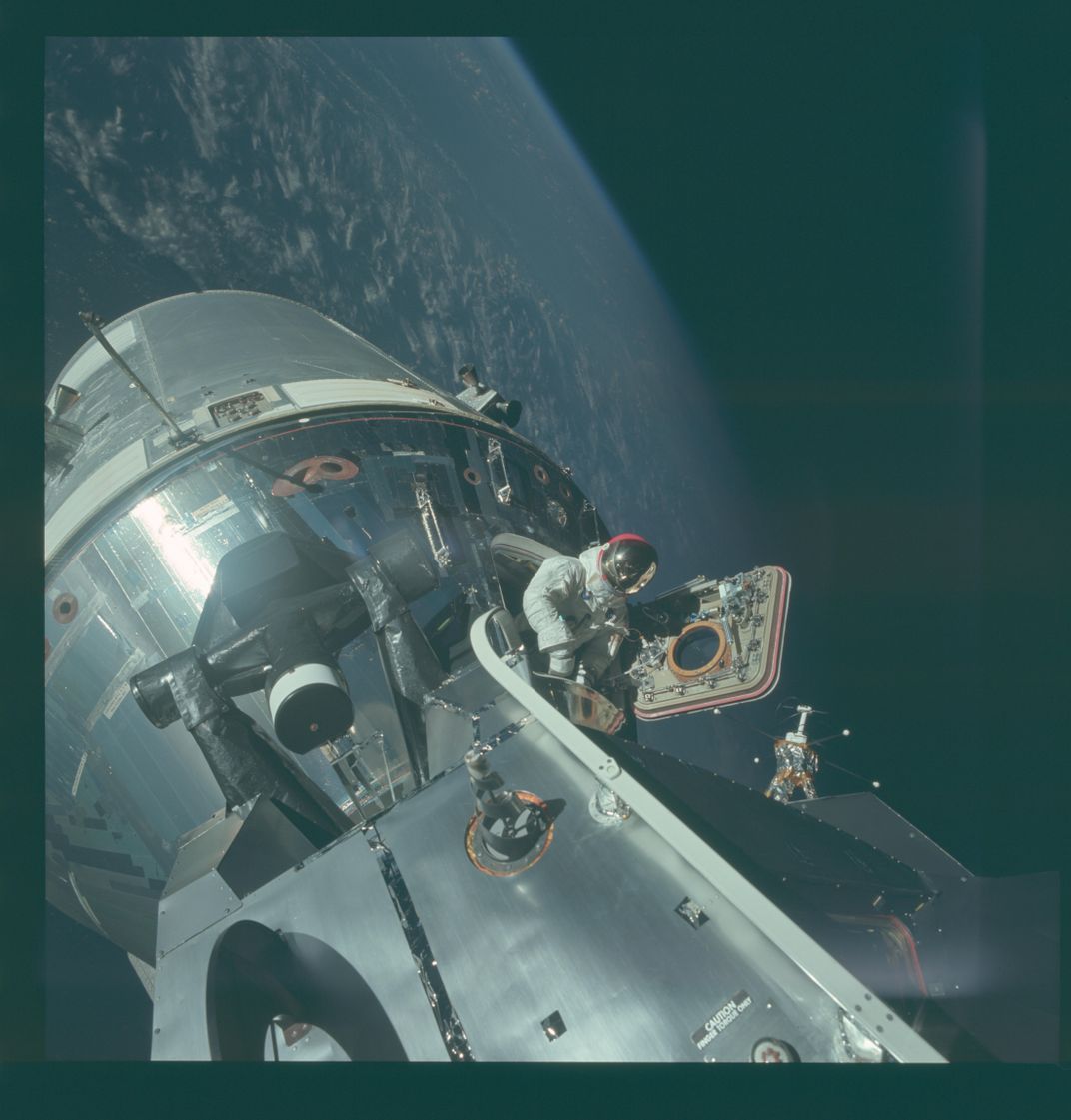

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/24/1c241975-642e-4af9-bda5-d8590461736d/719829main_orion_arrays_02_full.jpg)

Earlier this month, NASA quietly announced that it would "assess the feasibility of adding a crew to Exploration Mission-1, the first integrated flight of the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft." In other words, NASA could be putting humans into orbit around the Moon next year. According to the agency, the push to add astronauts to the equation came at the prompting of the White House.

NASA officials stress that the agency is merely undergoing feasibility studies, not committing to sending humans back to the Moon. “Our priority is to ensure the safe and effective execution of all our planned exploration missions with the Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System rocket,” NASA associate administrator William Gerstenmaier said in a statement last week. “This is an assessment and not a decision as the primary mission for EM-1 remains an uncrewed flight test.”

But the possibility of manned moonflight appears to be very real. Today, a senior administration official told PBS News Hour that President Donald Trump "will call for return of manned space exploration." Meanwhile, the private company SpaceX announced yesterday that it’s planning to send two space tourists around the Moon next year. If we do make a lunar return, how will a modern moon mission look compared to the Apollo missions of the 1970s?

The last time we traveled to the Moon, the world was very different. Astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt spent three days on our trusty satellite, collecting moon rocks, taking pictures with a then high-tech grainy color camera, and repairing their lunar rover with old-fashioned duct tape. On December 14, they blasted off the surface of the Moon in their disposable command module and returned to become the last humans to ever leave low-Earth orbit.

As the U.S. economy began to contract from an oil crisis and recession, the spending on the Apollo program became unpalatable to politicians, and future moon landings were abandoned.

Today, we carry cameras and computers more powerful than the Apollo astronauts had in our pockets. High-tech fibers would likely allow spacesuits that are much more flexible and comfortable than the Apollo astronauts had to stumble around in. It would be easy, in other words, to imagine how different a Moonwalk would be today.

First of all, NASA’s new generation of missions will use the Orion spacecraft, first announced in 2011, which are planned to permanently replace the retired Space Shuttles. Rising from the ashes of the cancelled Constellation space program that aimed to put humans back on the Moon by 2020, Orion was designed to ultimately carry humans into deep space—but not this soon. The Exploration Mission 1 (EM-1), which is scheduled to launch in September 2018, was originally meant to be an unmanned launch to test Orion and the new Space Launch.

Orion will leverage the massive advances in computing power and electronics since 1972, says space history curator Michael Neufeld of the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum. The Apollo command module had "millions" of gauges and dials scattered throughout its interior, Neufeld says, and required miles of wires behind every instrument panel to connect each one. Now, Orion will be able to use just a few flatscreens and computers to instantly bring up nearly every necessary measurement.

More powerful technology will allow more space for crew on a craft that is smaller and lighter than the original Apollo spacecraft. That will mean more space to carry supplies and more advanced sensing and photographic equipment, says Neufeld, who previously chaired the museum’s Space History Division and is the author of The Rocket and the Reich: Peenemünde and the Coming of the Ballistic Missile Era and Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War.

“Orion is significantly more capable than the capsule which carried the Apollo astronauts,” says NASA spokeswoman Kathryn Hambleton. One of the biggest improvements, she says, will be Orion’s ability to carry astronauts on longer missions—a necessity for potential future missions to Mars. With improved radiation shielding, solar panels and planned life support systems that will reclaim used water, Orion will soon be able to support four astronauts for up to three weeks.

“Orion is a highly advanced spacecraft which builds on the cumulative knowledge from all of our human spaceflight endeavors from short-term Apollo missions of the 1960s and 1970s to the present,” Hambleton says. It “combines and advances these technologies to enable human spaceflight missions of far greater scope, duration and complexity than previous missions, and represents the advent of a new era of space exploration.”

Yet while Orion takes advantage of cutting-edge innovations in space tech, its teardrop shape and basic design harken back to the Apollo command module that carried dozens of astronauts to the Moon in the 1960s and 70s.

The Apollo module was designed to look like a warhead, a shape that would maximize the amount of drag for slowing down the system in the atmosphere and preventing shockwaves from harming the astronauts. The design worked so well that NASA is returning to it, Neufeld says, referring to Orion as "a four-man Apollo."

The crew-carrying command modules will also use the same style of heat shield used by the Apollo missions to get crews safely back to Earth. These ablative heat shields will slowly burn up as the modules fall through the atmosphere, in effect making them single use, in contrast to the reusable system of resistant tiles developed for the space shuttles. (Damage to this system of tiles led to the 2003 Columbia disaster.)

Unlike the space shuttle, which astronauts flew like a plane to land back on the Earth, the Orion spacecraft will use parachutes to slow its fall and will land in the ocean. This is same basic system used in the Apollo program, though Hambleton notes that the parachute system is designed to be safer and deploy at higher altitudes to keep the craft more stable.

The other part of the equation for future missions—the Space Launch System that will carry the Orion modules out of Earth's grasp—will also feature a big difference from past missions. Unlike previous space shuttle launch systems, it won't be reusable, likely because the agency never achieved the planned cost savings from recovering and refurbishing the rockets.

In design, the SLS is "really derived from space shuttle technology," Neufeld says. But while Elon Musk's SpaceX and Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin are developing new fully reusable rockets, the SLS' large booster rockets will be allowed to burn up in the atmosphere like the rockets used by NASA before the space shuttle. "In other words, everything we did in the shuttle—reusable tiles, reusable launch vehicle—all that gets thrown away," Neufeld says.

In the end, it isn’t our technological abilities but our divergent visions about what space travel should look like that will influence our next trajectory into space. Some say humans should establish a base on the Moon and gain experience in long-term settlement there before heading to Mars. Others say it's unnecessary to waste time and money on a Moon landing, when we've already been there. Still others argue that, with advances in robot technology, it’s unnecessary to risk lives for future explorations.

"There's a larger question," Neufeld says. "Is human spaceflight a good thing to be doing? Are we doing this out of national pride—or something else?"

It's your turn to Ask Smithsonian.

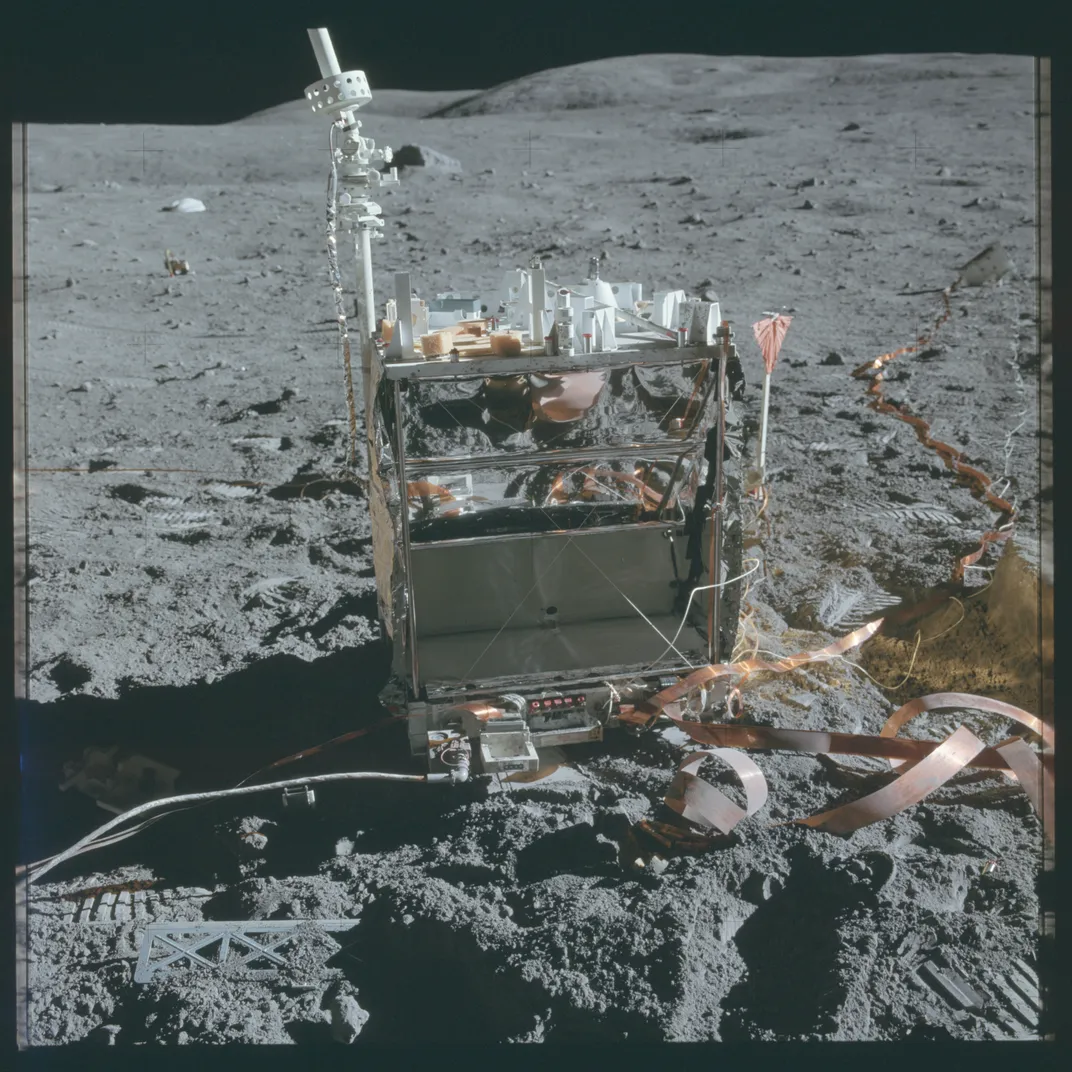

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/6f/496f66d6-1025-47d2-b0f0-b7673d512c13/as17-134-20475hr.jpg)