What’s Inside a 2,000-Year-Old, Shipwreck-Preserved Roman Pill?

Ancient Roman pills, preserved in sealed tin containers on the seafloor, may have been used as eye medicine

![]()

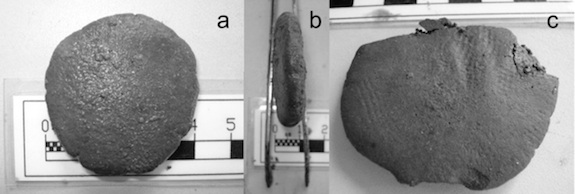

Though submerged in a shipwreck for millennia, the ancient Roman medicinal tablets were kept sealed in tin containers (left), ensuring the pills inside remained dry (right). Image via PNAS/Giachi et. al.

Around 120 B.C.E., the Relitto del Pozzino, a Roman shipping vessel, sank off the coast of Tuscany. More than two millennia later, in the 1980s and 90s, a team sent by the Archeological Superintendency of Tuscany began to excavate the ruins, hauling up planks of rotting wood.

“It wasn’t an easy task. The wreck is covered by marine plants and their roots. This makes it hard to excavate it,” underwater archaeologist Enrico Ciabatti told Discovery News in 2010. “But our efforts paid off, since we discovered a unique, heterogeneous cargo.”

The Relitto del Pozzino shipwreck contained a variety of cargo, including lamps that originated in Asia minor (above). Image courtesy of Enrico Ciabatti

That cargo, it turned out, included ceramic vessels made to carry wine, glass cups from the Palestine area and lamps from Asia minor. But in 2004, the archaeologists discovered it also included something even more interesting: the remains of 2,000-year-old medicine chest.

Although the chest itself—which had presumably belonged to a Roman doctor—was apparently destroyed, researchers found a surgery hook, a mortar, 136 wooden drug vials and several cylindrical tin vessels (called pyxides) all clustered together on the ocean floor. When they x-rayed the pyxides, they saw that one of them had a number of layered objects inside: five circular, relatively flat grey medicinal tablets. Because the vessels had been sealed, the pills had been kept completely dry over the years, providing a tantalizing opportunity for us to find out what exactly the ancient Romans used as medicine.

Now, as revealed today in a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of Italian chemists has conducted a thorough chemical analysis of the tablets for the first time. Their conclusion? The pills contain a number of zinc compounds, as well as iron oxide, starch, beeswax, pine resin and other plant-derived materials. One of the pills seems to have the impression of a piece of fabric on one side, indicating it may have once been wrapped in fabric in order to prevent crumbling.

Based on their shape and composition, the researchers venture that the tablets may have served as some sort of eye medicine or eyewash. The Latin name for eyewash (collyrium), in fact, comes from the Greek word κoλλυρα, which means “small round loaves.”

Although it remains to be seen just how effective this sort of compound would have been as an actual eye treatment, the rare glimpse into Roman-era medicinal practices is fascinating nonetheless. The vast majority of our knowledge of ancient medicine comes from writings—which may vary in accuracy and lack crucial details—so the presence of actual physical evidence is especially exciting.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)