What’s Really in That Tuna Roll? DNA Testing Can Help You Find Out

This rapidly evolving tech aims to empower consumers and shine a light on the food industry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/61/ec613cb0-9183-4904-af68-7d63538156b7/b13wck.jpg)

Gianpaolo Rando's first idea wasn't a great one.

A molecular biologist by training and a biotechnologist by trade, Rando wanted to use simplified DNA testing technology to help people—religious Jewish or Muslim tourists eating at unfamiliar restaurants, he thought— tell whether their supposedly pork-less meal really was pork-free. Think of it as a pregnancy stick, but for pork.

In 2015, he brought the idea to a speed-dating style investor meeting event in Geneva, where he lives. “Gianpaolo stood there and he had this card and he said, ‘I want people to rub this in their food and wait 30 minutes and if there’s pork in it, don’t it eat it,’” Brij Sahi, one of the investors at the meeting, says now with a laugh. “I was intrigued … but nobody is going to wait a half hour to eat their food while its sitting in front of them getting cold!”

Rando's idea missed the mark for a number of reasons; not only do people not want to wait around for the food to get cold before getting the all-clear to eat it, but also pork or no pork isn't the only question diners with specialized dietary requirements have about what they're eating. But the seed of an idea was there—what could a simplified, is-it-or-isnt-it DNA test with the ability to do for the food industry?

As DNA analysis has become easier, it has become an increasingly important tool for keeping the food industry in check, allowing manufacturers and outside agencies alike to police supply chains and ensure food purity. But taking a sample of the potentially offending food and sending it off to a lab, as most major manufacturers do, could take up to seven days.

“I said to myself, what if factory staff could test the food in 30 minutes?” says Rando. “I knew I could simplify further the DNA analysis so that it could be simple as a pregnancy test.”

Today Rando and Sahi are the co-founders of SwissDeCode, a Geneva-based company that offers made-to-order DNA testing kits for food manufacturers. Most are concerned about health and safety; the company has worked with several manufacturers to design kits that enable factory workers to test food products or supplies for harmful bacteria. They’ve also consulted with chocolate manufacturers (this is Switzerland, after all) trying to keep lactose out of their lactose-free chocolate.

But the avoid-pork idea hasn't totally been scrapped. This August, they launched their first off-the-shelf product, a pork DNA detection kit that will help sausage manufacturers, for example, make sure that their pork isn’t getting into their chicken sausages. Under food ingredient regulations, manufacturers must be clear in their labeling about what's going in what, for a variety of reasons, from allergies to religious observance to just making sure consumers know what they're eating.

The kits, which come in a disposable cardboard box, are intended to be user-friendly. The manufacturer takes a sample of the material to be tested, crushes it in the provided receptacle and then siphons up a bit of the crushed sample using a pipette. Then they put the sample into a tube containing a reagent, the substance that reacts with the bit of the DNA being identified, and stick the whole thing in a warm water bath.

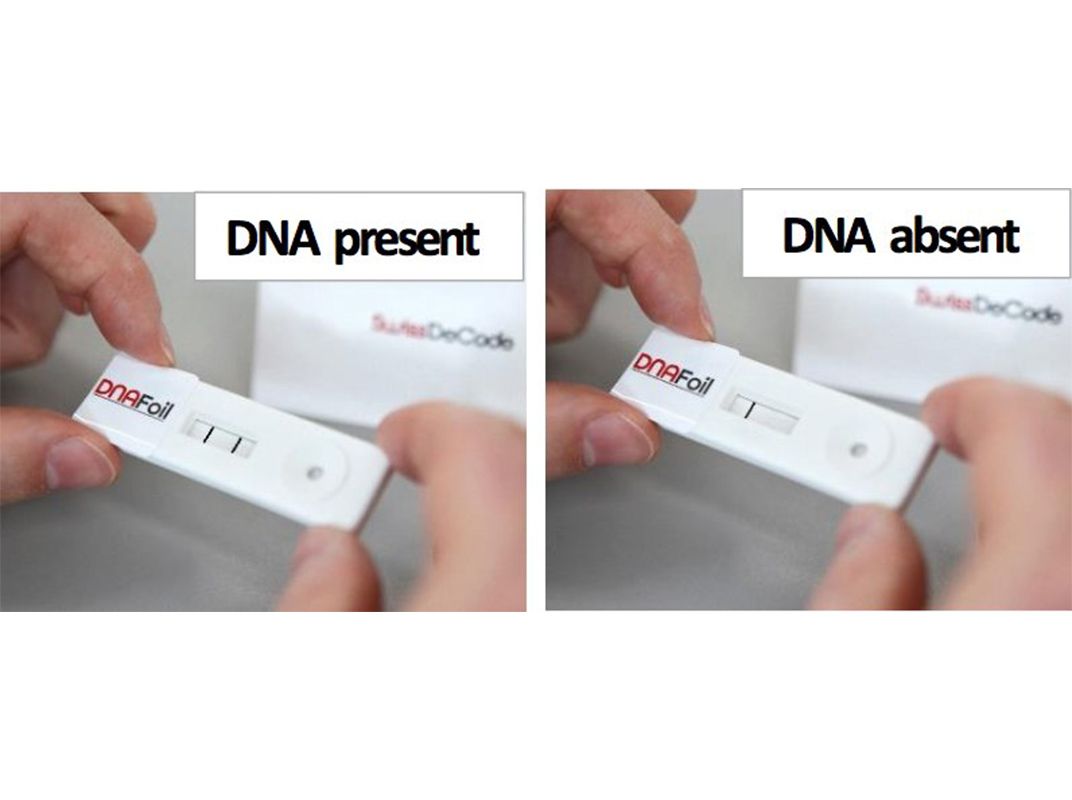

After about 20 minutes, the user removes the tube and dips a strip of reactive paper in it. There are two stripes on the paper, one that acts as a control and the other that tells you whether the DNA you’re testing for (i.e. pork) is present. Two horizontal lines appear when the DNA is present. The whole process takes under 30 minutes; the kit can be tossed in the trash after use. “We want factory staff to use it … so interpretation needs to be as easy as possible,” explained Rando.

Of course, while they may be as simple as a pregnancy test, pork detection kits are significantly more pricey. They currently sell at $990 for a package of five; the custom-made kits vary in price, but are similar in cost.

The applications of the pork detection kit are fairly obvious. “We are launching this kit as a way to secure the kosher and halal supply chain … Right now, all you’ll find is paperwork to secure that supply chain,” explained Sahi, the company’s CEO. “We are proposing that at any stage in the process, you can interject, take a sample, and determine that it is certified.” After all, the kosher and halal sector has grown by more than a third in the U.S. since 2010.

But their scope is much bigger than just halal or kosher foods, or even lactose-free chocolate: “Our vision is to build trust and secure the global food supply chain,” said Sahi. The result is an empowered manufacturer, who can make quick decisions in house to ensure that their supply chain is pure—and potentially save millions in revenue.

Swiss Decode’s goal feels particularly important right now. In the last five years alone, dozens of stories about adulterated, fake or otherwise contaminated food have made shocking headlines: Beef burgers contaminated with horsemeat. Lamb take-out that contains no lamb at all. The lie that is “Kobe” beef. Canned pumpkin pie filling that’s actually winter squash. Lobster that isn’t lobster, fish that isn’t the kind of fish it’s supposed to be, cheese that is partly wood pulp and “flavoring.”

Adulterated or false food is, of course, nothing new. Ancient Romans used lead acetate to sweeten inferior wines; the Medieval spice trade was rife with cheap substitutes, including plain old tree bark mixed in with cinnamon, dried wood with cloves, and sandalwood in saffron. In the 18th and 19th centuries, store-bought bread was whitened with chalk and alum.

But history is equally shaped by those who helped fight unsafe or dishonest food practices. One of the most important jobs in medieval Europe was the “garbler,” who, like a modern food inspector, examined spices for signs of tampering. At the same time, guilds, which tended to hold monopolies on their areas of trade, imposed strict regulations on the quality of products sold by members.

When standards became lax, scandals—often involving illness or even death—prompted public outcry and forced a reexamination of how food is made and sold. Though Upton Sinclair intended The Jungle, his 1906 expose of the horrific labor conditions in a Chicago meat-packing factory, to be a socialist call-to-arms, what readers remembered best was the stomach-turning revelation that they hadn’t been eating what they thought they’d been eating. The public outrage led to the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act, establishing what would later become the Food and Drug Administration. (Sinclair later famously claimed, "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.")

Today, we have far more precise tools to ferret out fraud. Since 2010, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Laboratory and Scientific Services Division has used DNA analysis to determine if a product entering the country has been mislabelled, violates the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (also known as CITES), or is meat from a quarantined country, i.e. chicken from a country with endemic avian flu. The increasing use of DNA “barcoding”—a method that uses a short genetic sequence from a given genome to identify a species—has made the quality of sequencing better and made CBP’s work easier.

“We’ve had cases in the past of shipments that were declared as big eye tuna that were actually yellow fin tuna,” said Matt Birck, branch chief of food and organic chemicals team for the CBP’s science division. “They’re both tunas, fine, but there’s a pretty substantial financial difference there.” One case sticks out in his mind: “We had one shipment declared as ‘cotton knitted ladies clothes’, but it was actually dehydrated pork.” It didn’t take DNA analysis to figure out that the import wasn’t what it said it was, but figuring out exactly what it was is part of the work they have to do.

DNA analysis, Birck says, is a “really powerful tool in our toolbox.” “Doing morphology on a whole fish is hard, doing it on a fish filet is impossible, but with the DNA analysis, I can tell you what it is,” he says.

But it isn’t only law enforcement agencies or biotech start-ups that are turning to DNA analysis to catch out fraudulent foods. In 2008, two teenagers in New York City made headlines after they used barcoding to determine that much of the fish peddled at Manhattan sushi restaurants was mislabeled, to put it kindly. One piece of the “luxury treat” white tuna, for instance, was actually Mozambique tilapia—a farm-raised and decidedly not luxury fish.

That was nearly a decade ago. At the time, the students had to send off their samples to the University of Guelph in Ontario, where the Barcode of Life database project started. Yet the advent of companies like SwissDeCode signals a crucial shift: Now, citizen scientists can simply perform the analysis themselves, either at their local community biolab or in their own homes.

SwissDeCode may be geared toward manufacturers, but the tech behind it comes squarely out of the DIY biology, citizen science ethos. And what it shows is that there’s a whole new cohort of people with the power to keep the food industry accountable.

…

Democratized DNA analysis is part of a larger DIY bio movement. A lot of it takes place in community biolabs that are available to non-scientists, like Brooklyn’s GenSpace; Hackuarium in Lausanne, Switzerland; London BioHackspace in London; BosLab in Somerville, Massacusetts; and BioCurious in Santa Clara, California. These biology-to-the-people labs are enabling citizen scientists to test their own tuna rolls to make sure it really is tuna.

Many of the workshop nights hosted by GenSpace, for example, are organized around food testing, because it’s easy to do and endlessly fascinating. “The other week, someone brought in some shrimp dumplings. They found that there were two types of shrimp in there, and then some other kind of strange mollusk,” laughed Nica Rabinowitz, community manager of GenSpace, when I interviewed her via Skype along with the lab’s co-founder and executive director Dan Grushkin.

The shrimp dumplings were brought in to one of GenSpace’s $10 BYOS (“bring your own sample”) classes, entry level classes for people from the local community to explore and learn about DNA analysis. “I think it is popular because it’s an easy access point,” said Grushkin. “And it’s a great way to get people started in this exploration of biotechnology. I think for the person showing up its exciting because eating is one of the pillars of our lives.“

“And it’s cool for them because they don’t have to find out from someone else, they can actually take control,” Rabinowitz added.

“Absolutely, it empowers the consumers … empowerment is a big part of this,” agreed Grushkin.

This kind of technology is also permeating into the home. Rando was inspired to create SwissDeCode’s kit after he beta-tested Bento Lab, the world’s first portable DNA lab. Priced at £999, Bento Lab is a laptop-sized device that contains the four pieces of equipment necessary for extracting, copying and visualising DNA. Bento Lab, which will be delivered to the more than 400 people who pre-ordered it this summer, is intended to educate and demystify DNA analysis, and yank it back from industry and academia.

“There is a big difference in attitude of something is perceived as closed—‘There’s no way I could do that, I’d have to be a Ph.D., I’d have to work in industry, otherwise I can forget it’— and thinking, ‘Well, I could do this on the weekend,’” says Philipp Boeing, co-founder of Bento BioWorks and a computer programmer by training.

And that attitude could make all the difference. Undergirding the democratization of biotechnology is the hopeful democratization of science in general, to show that truth exists and citizens can find it out for themselves. The trickle-down effects go far beyond catching out the ersatz tuna roll.

“I think the more people who understand the technology that exists, the more likely we’ll make communal decisions about how we want to make this technology function in our world,” says Grushkin. “When the lights are off, when things are happening in the dark, that’s when we should be concerned, but when folks are transparent and we can see what they’re doing and why they’re doing it, I would hope that we would make better decisions."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LindaRodriguezMcRobbieLandscape.jpg.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/LindaRodriguezMcRobbieLandscape.jpg.jpeg)