What’s the Secret of Hadrosaur Skin?

Were extra-thick hides the secret to why paleontologists have found so much fossilized hadrosaur skin?

![]()

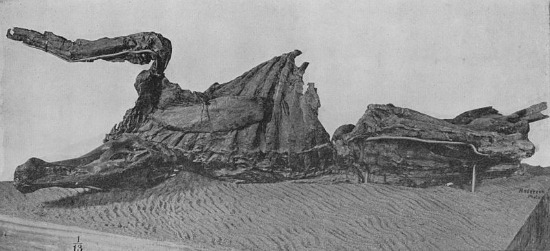

This famous Edmontosaurus skeleton was found with intricate traces of skin over much of its body. Image in Osborn, 1916, from Wikipedia.

Last week, I wrote about attempts by paleontologist Phil Bell and colleagues to extract biological secrets from fossilized traces of dinosaur skin. Among the questions the study might help answer is why so many hadrosaurs are found with remnants of their soft tissue intact. Specimens from almost every dinosaur subgroup have been found with some kind of soft tissue preservation, yet, out of all these, the shovel-beaked hadrosaurs of the Late Cretaceous are found with skin impressions and casts most often. Why?

Yale University graduate student Matt Davis has taken a stab at the mystery in an in-press Acta Paleontologica Polonica paper. Previously researchers have proposed that the abundance of hadrosaur skin remnants is attributable to large hadrosaur populations (the more hadrosaurs there were, the more likely their skin might be preserved), the habits of the dinosaurs (perhaps they lived in environments where fine-resolution fossilization was more likely) or some internal factor that made their skin more resilient after burial. to examine these ideas, Davis compiled a database of dinosaur skin traces to see if there was any pattern consistent with these ideas.

According to Davis, the large collection of hadrosaur skin fossils isn’t attributable to their population sizes or to death in a particular kind of environment. The horned ceratopsid dinosaurs–namely Triceratops–were even more numerous on the latest Cretaceous landscape, yet we don’t have as many skin fossils from them. And hadrosaur skin impressions have been found in several different kinds of rock, meaning that the intricate fossilization occurred in multiple types of settings and not just sandy river channels. While Davis doesn’t speculate about what made hadrosaurs so different, he proposes that their skin might have been thicker or otherwise more resistant than that of other dinosaurs. A sturdy hide might have offered the dinosaurs protection from injury in life and survived into the fossil record after death.

Still, I have to wonder if there was something about the behavior or ecology of hadrosaurs that drew them to environments where there was a greater chance of rapid burial (regardless of whether the sediment was sandy, silty or muddy). And the trouble with ceratopsids is that they have historically been head-hunted. Is it possible that we’ve missed a number of ceratopsid skin traces because paleontologists have often collected skulls rather than whole skeletons? The few ceratopsid skin fossils found so far indicate that they, too, had thick hides ornamented with large, scale-like structures. Were such tough-looking dinosaur hides really weaker than they appear, or is something else at play? Hadrosaurs may very well have had extra-sturdy skin, but the trick is testing whether that characteristic really accounts for the many hadrosaur skin patches resting in museum collections.

Reference:

Davis, M. 2012. Census of dinosaur skin reveals lithology may not be the most important factor in increased preservation of hadrosaurid skin. Acta Paleontologica Polonica http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2012.0077

Osborn, H. 1916. Integument of the iguanodon dinosaur Trachodon. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. 1, 2: 33-54

Sternberg, C.M. 1925. Integument of Chasmosaurus belli. The Canadian Field Naturalist. XXXIX, 5: 108-110

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)