Why Did the Carolina Parakeet Go Extinct?

It hasn’t been seen for a century. But will the bird species ever fly again?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/87/61878868-0d83-418a-9ad1-545b12fd684c/may2018_a04_prologue-wr.jpg)

Among all the birds and mammals that once inhabited American forests and still would today if human settlers had not driven them to extinction, the Carolina parakeet seems out of place. A native green parrot in the eastern United States? Parrots are supposed to decorate palm trees in the tropics not the cypress of temperate forests.

Yet there are 19th-century accounts of North America’s only native parrot species from places as far-flung as Nebraska and Lake Erie, though even then the noisy flocks were in decline. “In some districts, where twenty-five years ago they were plentiful, scarcely any are now to be seen,” John James Audubon warned in 1831. The last Carolina parakeet in captivity, a male named Incas, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918. But the species may squawk again: Today geneticists and conservation biologists often mention the bird as a candidate for “de-extinction,” the process of recreating a vanished species—or at least an approximation of it—from preserved genetic material. De-extinction projects are already underway for the passenger pigeon and the woolly mammoth. (The latter project of adding mammoth DNA to the Asian elephant genome is further along.)

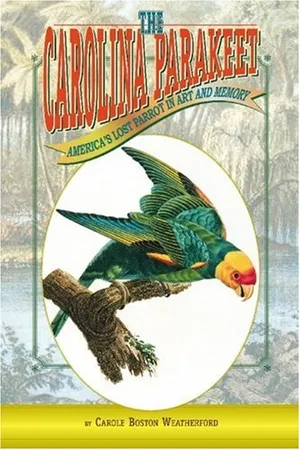

The Carolina Parakeet: America's Lost Parrot In Art And Memory

In America there was once a gem in The Great Forest; a winged jewel rivalling any in the tropics. It was the Carolina Parakeet, North America's only native parrot. Curiously, within the span of a century, the great flocks dwindled to nothing, and this thing of beauty disappeared. This is the sobering story of how a young nation loved, laid waste and lost its only parrot.

Bringing the Carolina parakeet back from the dead wouldn’t be easy, says Ben Novak, the lead scientist at Revive & Restore, a clearinghouse for such efforts. The birds disappeared so quickly that much of their biology and ecology is a mystery today. Scientists cannot even say why the Carolina parakeet went extinct, though deforestation, disease, persecution by farmers and competition from honeybees are all possibilities.

Nearly a century after the last reliable sighting of the bird in the wild, scientists are looking for answers. Kevin Burgio, a biologist at the University of Connecticut, published a study last year of what he calls “Lazarus ecology” in the journal Ecology and Evolution. He built a data set of historical Carolina parakeet sightings and collection sites, and combined it with climate data to create a map of where the birds lived. He concluded that the bird’s home range was much smaller than previously believed, with one subspecies inhabiting Florida and the Southeastern coastline and another the South and Midwest. Scientists from the New York State Museum and New Mexico State University have sequenced the bird’s DNA, and chemical analysis of preserved feathers may reveal the makeup of its diet. Next, Burgio is trying to piece together the extinction process from the historical record, which includes sightings by Thomas Jefferson and Lewis and Clark.

And even if the Carolina parakeet never flies again, what scientists learn about this vanished American bird could keep its endangered tropical cousins aloft.

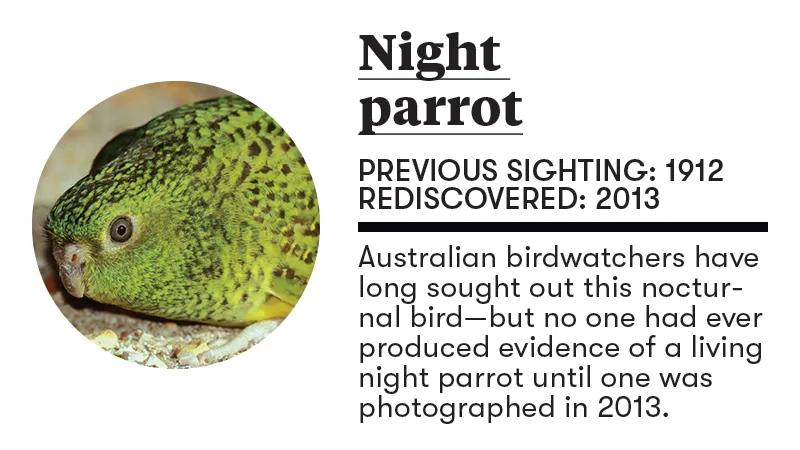

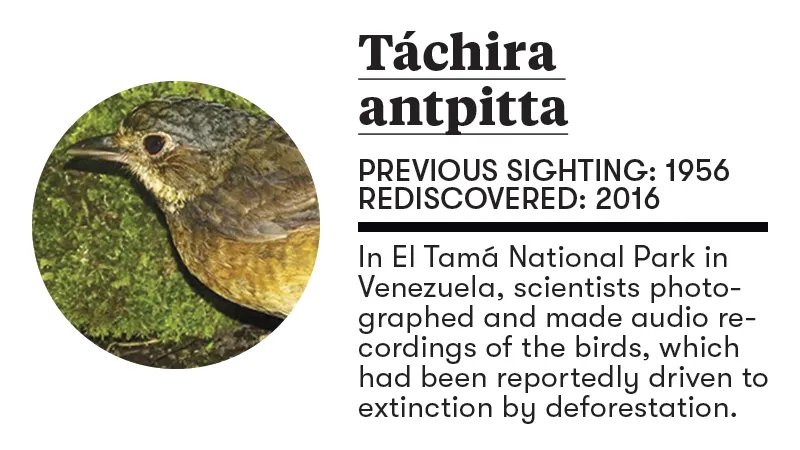

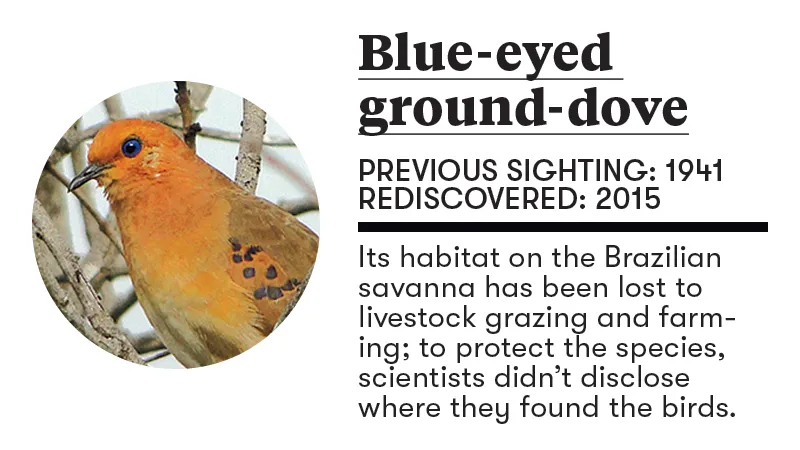

Lazarus Birds

Most extinct species are in fact long gone, but now and then scientists rediscover a plant or animal in the wild that hadn’t been seen in decades. Out of some 350 “Lazarus species” identified worldwide since 1889, here are several of the most recently sighted birds.

Editor's Note: In “The Lost Parrot,” we mistakenly characterized the Carolina parakeet as “North America’s only native parrot species.” In fact, the endangered thick-billed parrot, now found in Mexico, is also native to North America.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.