Why Do We Keep Naming New Species After Characters in Pop Culture?

Why are ferns named after Lady Gaga and microbes named after sci-fi monsters?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131105100138lady-gaga-fern-copy.jpg)

In October 2012, a Duke University biologist named a newly discovered genus of ferns after Lady Gaga. Then, in December, Brazilian scientists named a new bee species Euglossa bazinga, after a catch phrase from a TV show.

“The specific epithet honors the clever, funny, captivating “nerd” character Sheldon Cooper, brilliantly portrayed by the North American actor James Joseph “Jim” Parsons on the CBS TV show ‘The Big Bang Theory,’” they wrote . Scientists weren’t done honoring dear old Sheldon: This past August, he also got a new species of jellyfish, Bazinga rieki, and was previously heralded with an asteroid.

These organisms and astronomical entities are far from the first to be given cute pop culture-inspired names. The tradition goes back at least a few decades, with bacteria named after plot elements from Star Wars, a spider named for Frank Zappa and a beetle named after Roy Orbison.

All of which makes an observer of science wonder: Why do we keep naming species after figures from movies, music and TV shows?

“Mostly, when you publish research about termite gut microbes, you don’t get much interest—even most of the people in the field don’t really give a crap,” says David Roy Smith, a scientist at University of Western Ontario who studies these and other types of microorganisms for a living. Recently, though, he saw firsthand that this doesn’t always have to be the case: His colleagues discovered two new species of protists that lived inside termite guts and helped them digest wood, and the group named them Cthulhu macrofasciculumque and Cthylla microfasciculumque, after the mythical creature Chtulhu, created by influential science fiction writer H.P. Lovecraft.

“I remember Erick James, who was the lead author on the study, telling us that he’d named it something cool right before we submitted it, but we didn’t really pay him much attention,” Smith says. “Then, afterwards, day after day, he kept coming into the lab telling us he’d seen an article on the species on one site, then another. By the second week, we were getting phone calls from the Los Angeles Times.” Eventually, James was invited to present work on the protists at an annual conference of H.P. Lovecraft fans, and a search for Cthulhu macrofasciculumque now yields nearly 3,000 results.

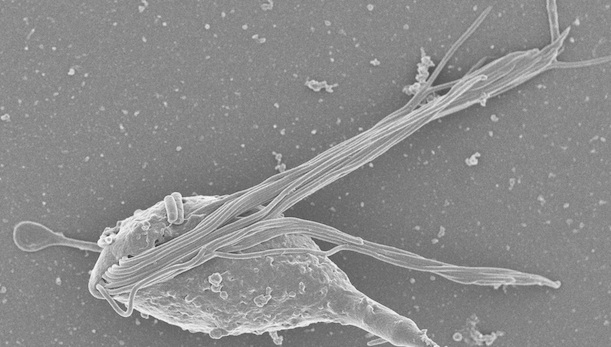

Cthulhu macrofasciculumque, the protist species named after H.P. Lovecraft’s legendary monster. Image via University of British Columbia

The episode prompted Smith to take silly scientific names seriously for the first time—so much so that he wrote an article about the phenomenon in the journal BioScience last month. For him, a scientist’s incentive in giving a new discovery this sort of name is obvious. “Science is a competitive field, if you can get your work out there, it’s only going to help you,” he says. Mainstream press attention for an esoteric scientific discovery, he feels, can also garner increased citations from specialists in the field: A microbe researcher is likely to notice a Cthulhu headline on a popular news site, then think of it when she’s writing her next paper.

But is naming species after sci-fi villains and TV catch phrases good for science as a whole? Smith argues that it is. “Scientists are perceived to be serious and stiff,” he says. “When you put some entertainment and fun into your work, the general public gets a kick out of it, and appreciates it a little more.” In an age when public funding for science is drying up, garnering every bit of support can make a difference in the long-term.

There are critics who take issue with the idea, though. It’s easy to imagine, for instance, that the vast majority of the people who shared articles about Lady Gaga’s fern focused mostly on the pop star, rather than the botanical discovery.

Moreover, species names are forever. “The media interest will subside, but the name Cthulhu will stay and plague the biologists who deal with this organism, tomorrow and 200 years from now. It’s difficult to spell and pronounce and utterly mysterious in meaning for people who don’t know Lovecraft,” Juan Saldarriaga, a research fellow at the University of British Columbia, told Smith for his BioScience article. “And for what? People saw the name on their Twitter account, smiled, said ‘Cool,’ and then went on with their lives.”

For his part, Smith feels that all species names inspired by pop culture are not created equal. The Cthulhu microbe, for example, is named after a legendary character with legions of fans nearly a century after its creation; moreover, the protist itself, with a tentacle-like head and movements resembling an octopus, calls to mind Lovecraft’s original Cthulhu character. This is a far cry from, say, a bee, jellyfish and asteroid all named for a catch phrase from a current (and likely to be eventually forgotten) primetime sitcom. “You can do it tactfully, and artfully,” Smith says. “Other times, people might be reaching, and just desperately want to give something a popular name.”

It’s also worth remembering one of the earliest instances of naming a discovery after heroes from contemporary culture: the planets, which the ancient Greeks named after their gods–for example, the gods of war and love. The planets were later rebranded by the Romans—and nowadays, the average person might have no idea that Mars and Venus were gods in the first place—but their names live on.

This blogger’s opinion? Long live Cthulhu.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)