The Musical Performance “Sight Machine” Reveals What Artificial Intelligence Is “Thinking” About Us

Like artist Trevor Paglen’s other work, the show asked viewers to reexamine the human relationship to technology

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/1c/e81cd4a6-817b-40f6-8444-7fc614c6544e/sight3_181025_066.jpg)

Last year, Facebook created two chatbots and asked them to begin talking to each other, practicing their negotiation skills. The bots, it turns out, were pretty good at negotiating—but they did it using their own made-up language that was incomprehensible to humans.

This is where the world is going. Computers are creating content for each other, not us. Pictures are being taken by computers, for other computers to view and interpret. It's all happening quietly, often without our knowledge or consent.

So learning how to see like a computer—making these machine-to-machine communications visible—may be the most important skill of the 21st century.

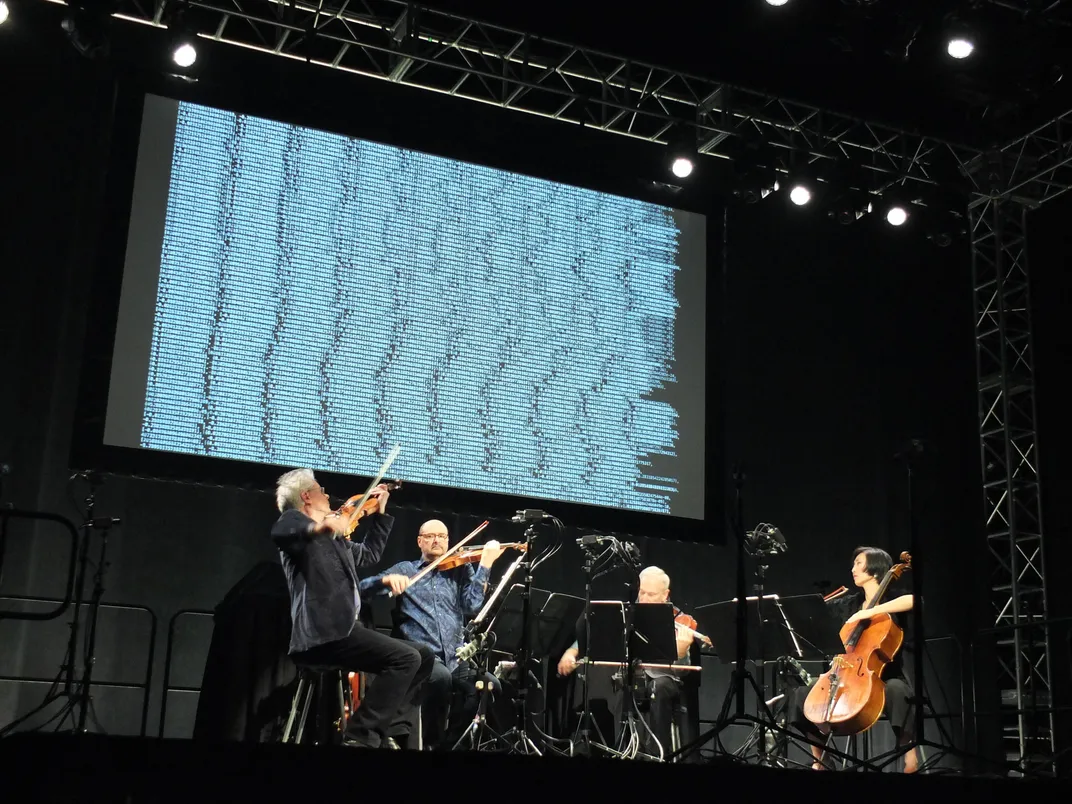

On October 25, 2018, Kronos Quartet—David Harrington, John Sherba, Hank Dutt, and Sunny Yang—played a concert at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. They were watched by 400 humans and a dozen artificial intelligence algorithms, the latter courtesy of Trevor Paglen, the artist behind the "Sites Unseen" exhibition, currently on view at the museum.

As the musicians played, a screen above them showed us humans what the computers were seeing.

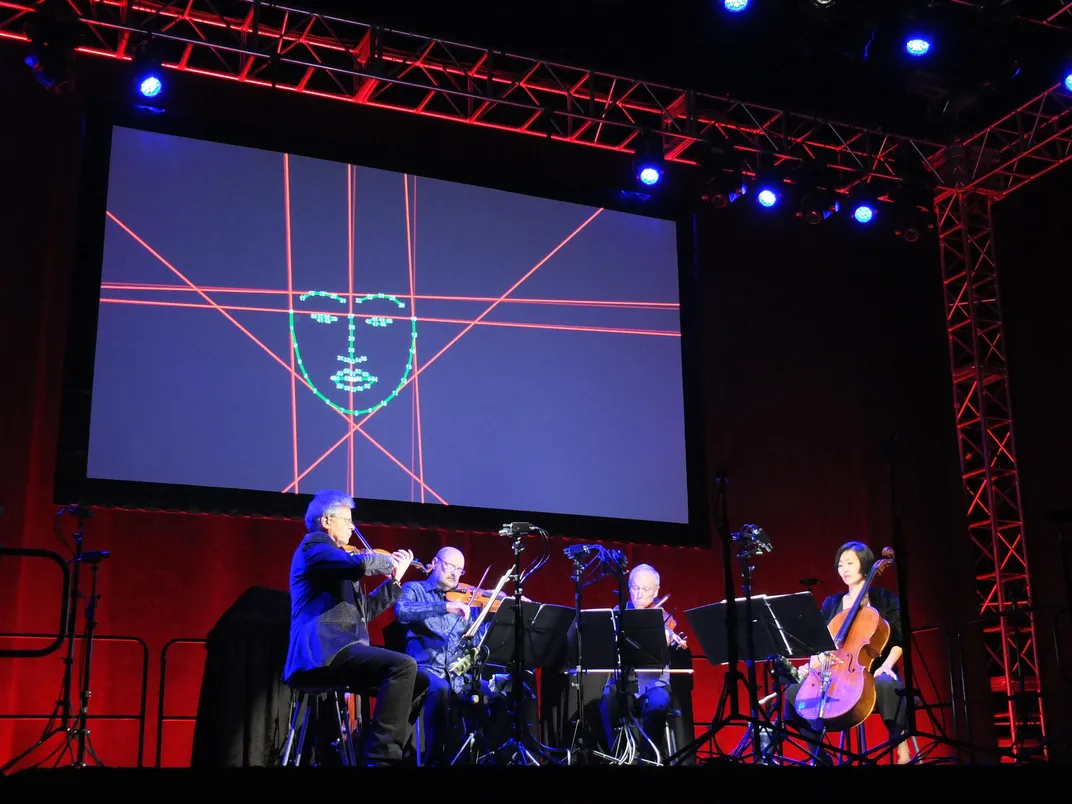

As Kronos worked its way through a mournful piece originally from the Ottoman Empire, on the screen overhead algorithms detected the musicians' faces, outlining lips, eyes and nose for each person (and occasionally saw "ghost" faces where there were none—often in Kronos founder Harrington's mop of hair). As the algorithms grew more advanced, the video feed faded away until only neon lines on a black background remained. Finally, the facial outlines faded away until an abstract arrangement of lines—presumably all the computer needed to understand "face," but completely unintelligible to humans—was all that was left.

The East Coast debut of the performance titled "Sight Machine," like Paglen's other work, asked viewers and listeners to learn how to see like computers do, and to reexamine the human relationship to technology—the phones in our pockets, and the eyes in the sky, and everything in between.

It’s 2018, and the idea that cell phones are watching us no longer feels like a conspiracy theory posed by a tin-foil-hat-wearing basement blogger. Google was caught earlier this year tracking Android phone users’ locations, even if users disabled the feature. Many people are convinced that our phones are listening to us to better serve up ads—Facebook and other companies deny these charges, although it is technically and legally possible for them to do so. Tech journalists Alex Goldman and PJ Vogt investigated and found the same thing: There’s no reason why our phones wouldn’t be listening, but on the other hand, advertisers can glean enough information on us through other methods that they just don’t need to.

It’s in this context that "Sight Machine" was performed. The dozen or so cameras watching Kronos Quartet sent live video from the performance to a rack of computers, which uses off-the-shelf artificial intelligence algorithms to create the eerie visuals. The algorithms are the same ones used in our phones to help us take better selfies, ones used by self-driving cars to avoid obstacles, and ones used by law enforcement and weapons guidance. So while the results on screen were sometimes beautiful, or even funny, there was an undercurrent of horror.

“What I am amazed by with this particular work is, he's showing us something that is—and this is true of all of his work—he’s showing us something that's disturbing and he's doing it using tricks,” says John Jacob, the museum's curator for photography, who organized "Sites Unseen.”

“It’s a deliberate trick,” he says, "and it works.”

Later, sophisticated facial recognition algorithms made judgments about the members of Kronos, and displayed their results on a screen. "This is John [Sherba]. John is between 24-40 years old," said the computer. "Sunny [Yang] is 94.4% female. Sunny is 80% angry and 10% neutral."

"One of the things I hope the performance shows," Paglen says, "is some of the ways in which the kind of perceiving the computers do is not neutral. It's highly biased. . . with all kinds of political and cultural assumptions that are not neutral." If the gender-classification system says that Sunny Yang is 94.4 percent female, then that implies that someone is 100 percent female. "And who decided what 100 percent female is? Is Barbie 100 percent female? And why is gender a binary?" Paglen asks. "Seeing that happen at a moment where the federal government is trying to literally erase queer-gendered people, it's funny on one hand but to me it's also horrifying."

A later algorithm dispensed with the percentages and moved to simply identify objects in the scene. "Microphone. Violin. Person. Jellyfish. Wig." (The latter two are clearly mistakes; the algorithm seems to have confused Hank Dutt for a jellyfish and Harrington's real hair for a toupee.) Then the classifications got more complex. "Sunny is holding a pair of scissors," the machine said as light glinted off her cello strings. "John is holding a knife." What would happen if the classifier gave this—incorrect—information to law enforcement, we'll never know.

Most end users of AI platforms—who are not artists—might argue that these systems may have their own biases, but always receive a final sign-off by a human. An Amazon-made algorithm, Rekognition, which the company sells to law enforcement and possibly ICE, famously misidentified 28 members of Congress as people who had been charged with a crime by comparing their faces to mugshots in a publicly available database. At the time, Amazon argued that the ACLU, which used the system to make the matches, had used Rekognition incorrectly. The company said that the system's default setting for matches, called a "confidence threshold," is just 80 percent. (In other words, the algorithm was only 80 percent sure that Rep. John Lewis was a criminal.) An Amazon spokesperson said that it recommends police departments use a confidence threshold of 95 percent, and that "Amazon Rekognition is almost exclusively used to help narrow the field and allow humans to expeditiously review and consider options using their judgment.” Computers may be communicating with each other, but—for now—they're still asking humans to make the final call.

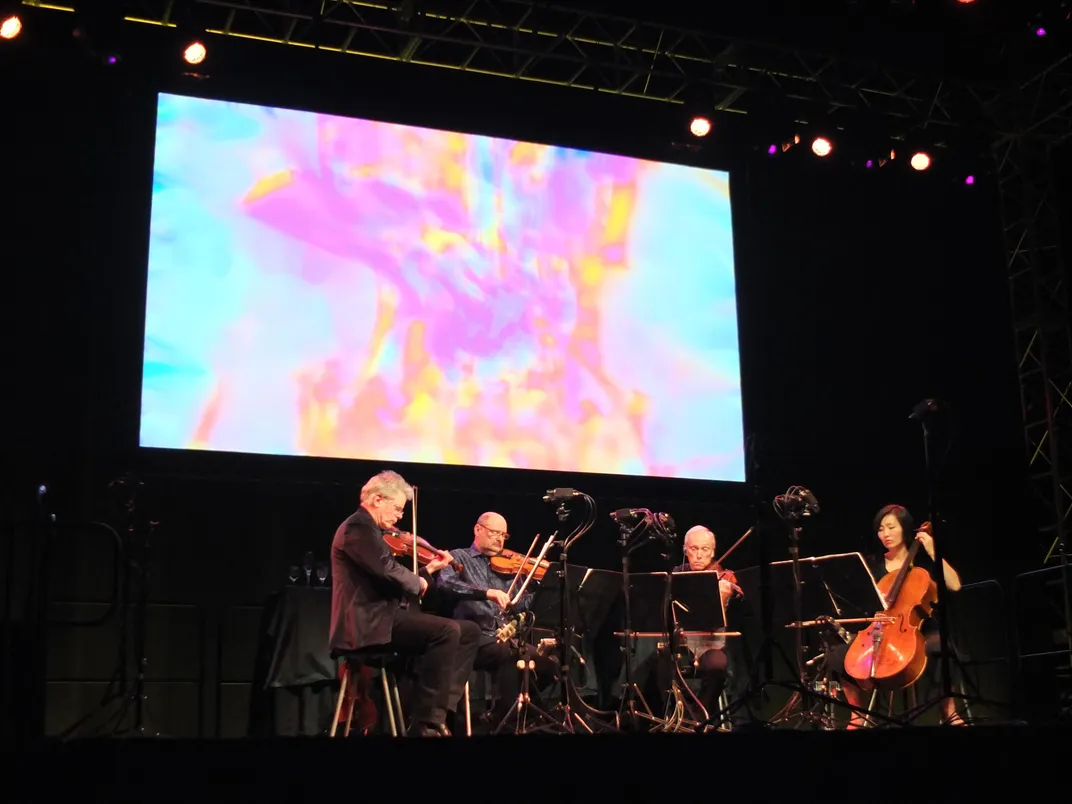

The music, chosen by Paglen with input from Kronos, also has something to say about technology. One piece, "Powerhouse," by Raymond Scott, is "probably most famous for being used in cartoons in factory scenes," Paglen says. "If you ever see a factory kind of overproducing and going crazy, this is often the music that speaks to that. For me it's a way of kind of thinking about that almost cartoonish industrialization and kind of situate them within a technology context." Another piece, "Different Trains" by Steve Reich, closed the set. Kronos performs only the first movement, which is about Reich's childhood in the 1930s and '40s; Paglen says he thinks of the piece as celebrating "a sense of exuberance and progress that the trains are facilitating."*

It was coupled with images from a publicly available database called ImageNet, which are used to teach computers what things are. (Also called "training data," so yes, it's a bit of a pun.) The screen flashed images impossibly fast, showing examples of fruit, flowers, birds, hats, people standing, people walking, people jumping and individuals like Arnold Schwarzenegger. If you wanted to teach a computer how to recognize a person, like Schwarzenegger, or a house or the concept of "dinner," you would start by showing a computer these thousands of pictures.

There were also short video clips of people kissing, hugging, laughing and smiling. Maybe an AI trained on these pictures would be a benevolent, friendly one.

But "Different Trains" is not just about optimism; the later movements, which Kronos didn't play Thursday but are "implied" by the first, are about how the promise of train travel was appropriated to become an instrument of the Holocaust. Trains, which seemed like technological progress, became the vehicles in which tens of thousands of Jews were relocated to death camps. What seemed like a benevolent technology became subverted for evil.

"It's like, 'What could possibly go wrong?" Paglen says. "We're collecting all the information on all the people in the world.'"

And in fact, as "Different Trains" ended, the focus shifted. The screen no longer showed images of Kronos or the training data from ImageNet; instead, it showed a live video feed of the audience, as facial recognition algorithms picked out each person’s features. Truly, even when we think we are not being watched, we are.

To report this story, I left my house and walked to the subway station, where I scanned an electronic card linked to my name to go through the turnstile, and again when I left the subway downtown. Downtown, I passed a half-dozen security cameras before entering the museum, where I spotted at least two more (a Smithsonian spokesperson says the Smithsonian does not use facial recognition technology; the D.C. metropolitan police department says the same about its cameras).

I recorded interviews using my phone and uploaded the audio to a transcription service that uses AI to figure out what I, and my subjects, are saying, and may or may not target advertising toward me based on the content of the interviews. I sent emails using Gmail, which still "reads" everything I send (although no longer to serve me ads).

During the reporting process, as I was walking through the city, I ran into—I am not making this up—the Google Street View car. Twice. It’s not paranoia if they really are watching you, right?

So what's left, in this world where computers are doing the seeing, and possibly making judgments about us? "Sight Machine" urges us to learn how to think like a computer—but it also reminds us that there are some parts of us that are, for now, still fully human.

Music, Paglen says, "is something that's really not quantifiable. . . when you watch a computer vision system essentially interrogating performers, it really for me points out that vast gulf in perceptions between the way that we perceive culture and emotion and meaning. . . and all the ways in which those are invisible to autonomous systems."

Or as Harrington puts it, you can be making music with a violin made of wood or one made on a 3D printer. You can use a carbon-fiber bow or one made of pernambuco wood. But, he says, the bow still needs to be pulled across the strings. The music "becomes more precious because it's handmade."

And for now, that's still something only we can do. The machines may no longer need us. But when it comes to the solemn sound of a bow on a violin string, and the emotional strings that note tugs on, we don't need the machines.

“Trevor Paglen: Sites Unseen,” curated by John Jacob, continues at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. through January 6, 2019. It is scheduled to travel to The San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art Feb. 21-June 2, 2019.

*Editor's note, November 2, 2018: This story has been edited to clarify the intended meaning and origin story of Steve Reich's "Different Trains" composition.