Patricia Brennan never intended to become a champion of the vagina. Her journey, in fact, began with a penis.

It was a late summer afternoon in 2000, and the 28-year-old Colombian biologist was stalking her study animal, a squat gray-blue bird called the great tinamou in the dense Costa Rican rainforest. As always, the forest floor was dark and shadowy, the sunlight swallowed up by the upper canopy. It was stiflingly humid; she was sweating through her protective gear. “You could die in that forest, and there would be no trace of you in just a few months,” she recalls. “You would disappear completely.”

That’s when she heard it: a pure, whistling tone, with an undertone of sadness. A male tinamou, calling for a mate. As she held her breath, a female appeared from the dense underbrush. She ran up to him, backed away, then chased him again. Finally she crouched down with her tail in the air, inviting him to mount. As Brennan watched through her binoculars, the male clambered clumsily onto her back. Brennan will never forget what happened next.

For most birds, mating is an artless affair. That’s because they don’t have external genitalia, just a multipurpose opening under the tail used to expel waste, lay eggs and have sex. (Biologists usually call this orifice a cloaca, which means “sewer” or “drain” in Latin. Brennan simply refers to it as the vagina, since it performs all the same functions and then some.) They briefly rub genitals together in an act known as a “cloacal kiss,” in which the male transfers sperm into the female. The whole event takes seconds.

But this time, the pair began waddling around, glued together. The male started thrusting. When he finally detached, she saw something dangling off him—something long, white and curly.

“What the hell is that thing?” she remembers thinking. “Oh, God, he’s got worms.”

Then she had another thought: “Man, is that a penis?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d8/12/d812d49f-76cc-4545-8eef-c49ee4b65654/img_8297_web.jpg)

Birds, she thought at the time, didn’t have penises. In her two years studying them at Cornell University, a world leader in avian research, she’d never once heard her colleagues mention a bird penis. And anyway, this certainly didn’t look like any penis she had ever seen—it was ghostly white, curled up like a corkscrew, thin as a piece of cooked spaghetti. Why would such an organ have evolved, only to have been lost in almost all birds? That would have been “the weirdest evolutionary thing,” she says.

When she returned to Cornell, she decided to learn everything there was to know about bird penises—which turned out to be not so much. Ninety-seven percent of all bird species have no phallus. Those that did, including ostriches, emus and kiwis, sported organs quite different from the mammalian variety. Corkscrew-shaped, they exploded out into the female in one burst, and engorged with lymphatic fluid rather than blood. Sperm traveled down spiraling grooves along the outside.

Brennan had been the first to observe a penetrative penis in this species of tinamou. Only later would she ask the question that would distinguish her from all her peers: If this was the penis, then what were the vaginas doing? “Obviously you can’t have something like that without some place to put it in,” she would later tell the New York Times. “You need a garage to park the car.” For the first time, she wondered about the size, shape, and function of that … er … garage.

In 2005, before she turned her lens to vaginas, the pursuit of penises led Brennan to the University of Sheffield in the English countryside. After realizing that “there is a huge gaping hole in our knowledge of this very fundamental part of bird biology,” she had pivoted her research and was now focusing on bird-penis evolution. She was here to learn the art of dissecting bird genitalia from Tim Birkhead, an evolutionary ornithologist. She got to work dissecting quail and finches, which had little in the way of outer genitalia. Next, she opened up a male duck from a nearby farm, and gasped.

The tinamou’s penis had been thin, like spaghetti. This one was thick and massive, but with the same recognizable spiral shape. Whoa, she thought. Wait a minute—where is this thing gonna go?

No one seemed to have an answer. The problem was, the typical bird-dissection technique focused almost entirely on the male. When researchers did dissect a female duck, they sliced all the way up through the sides of the vagina to get at the sperm-storage tubules near the uterus (in birds, it’s called the shell gland), distorting their true anatomy. They tossed the rest out, unexamined. When she asked Birkhead what the inside of a female duck’s reproductive tract looked like, she recalls, he assumed it was the same as any other bird: a simple tube.

But she knew there was no way an appendage as complex and unusual as the duck penis would have evolved on its own. If the penis were a long corkscrew, the vagina ought to be an equally complex structure.

The first step was to find some female ducks. Brennan and her husband drove out to one of the surrounding farms and purchased two Pekin ducks, which she euthanized without ceremony on a bale of hay. (Brennan’s husband is used to these kind of excursions: “He brings me roadkill as a nuptial gift,” she says.) Instead of slicing the reproductive tract up the sides, she spent hours carefully peeling away the tissues, layer by layer, “like unwrapping a present.” Eventually, a complex shape emerged: twisted and mazelike, with blind alleys and hidden compartments.

When she showed Birkhead, they both did a double-take. He had never seen anything like it. He called a colleague in France, a world expert on duck reproductive anatomy, and asked him if he’d ever heard of these structures. He hadn’t. The colleague went to examine one of his own female specimens, and reported back the same thing: an “extraordinary vagina.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/85/0b/850b14f5-4424-4f43-9fae-1c09cc5b98cd/duckvagina2_web.jpg)

To Brennan, it seemed that females were responding in some way to males, and vice versa. But there was something odd going on: the vagina twisted in the opposite direction of the male’s. In other words, this vagina seemed to have evolved not to accommodate the penis, but to evade it. “I couldn’t wrap my head around it. I just couldn’t,” Brennan says. She preserved the structures in jars of formaldehyde and spent days turning them over, trying to figure out what could explain their complexity.

That’s when she began thinking about conflict. Duck sex, she knew, could be notoriously violent. Ducks tended to mate for at least a season. However, extra males lurked in the wings, ready to harass and mount any paired female they could get their hands on. This often leads to a violent struggle, in which males injure or even drown the female. In some species, up to 40 percent of all matings are forced. The tension is thought to stem from the two sexes’ competing goals: The male duck wants to sire as many offspring as possible, while the female duck wants to choose the father of her children.

This story of conflict, Brennan suspected, might also shape duck genitalia. “That was the part where I was like: holy cow,” she says. “If that’s really going on, this is nuts.” She started contacting scientists across North and South America to collect more specimens. One was Kevin McCracken, a geneticist at the University of Alaska who, while out on a wintry jaunt, had discovered the longest known bird phallus on the Argentine lake duck, which unraveled to a stunning 17 inches. He suggested that perhaps the male was responding to female preference—wink-wink, nudge-nudge—but hadn’t bothered to actually examine the female.

When Brennan called him up, he was more than happy to help her collect more specimens. Today, he admits that perhaps the reason he hadn’t considered looking at the female side of things was a result of his own male bias. “It was fitting that a woman followed this up,” he says. “We didn’t need a man to do it.”

By carefully dissecting the genitals of 16 species of waterfowl, Brennan and her colleagues found that ducks showed unparalleled vaginal diversity compared to any known bird group. There was a lot going on inside those vaginas. The main purpose, it appeared, was to make the male’s job harder: It was like a medieval chastity belt, built to thwart the male’s explosive aim. In some cases, the female genital tract prevented the penis from fully inflating, and was full of pockets where sperm went to die. In others, muscles surrounding the cloaca could block an unwanted male, or dilate to allow entry to a preferred suitor.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/82/85/82858bb0-76e0-4da4-832b-ddb1ebc5ae11/duckvaginafrombrennan_web.jpg)

Whatever the females were doing, they were succeeding. In ducks, only 2 to 5 percent of offspring are the result of forced encounters. The more aggressive and better endowed the male, the longer and more complex the female reproductive tract became to evade it. “When you dissected one of the birds, it was really easy to predict what the other sex was going to look like,” Brennan told the New York Times. It was a struggle for reproductive control, not bodily autonomy: Although a female couldn’t avoid physical harm, her anatomy could help her gain control over the genes of her offspring after a forced mating.

The duck vagina, Brennan realized, was hardly the passive, simple structure that biologists had made it out to be. In fact, it was an expertly rigged penis-rejection machine. But what about in other animal groups?

A world opened up before Brennan’s eyes: the vast variety of animal vaginas, wonderfully varied and woefully unexplored. For centuries, biologists had praised the penis, fawning over its length, girth, and weaponry. Brennan’s contribution, simple as it may seem, was to look at both halves of the genital equation. Vaginas, she would learn, were far more complex and variable than anyone thought. Often, they play active roles in deciding whether to allow intruders in, what to do with sperm, and whether to help a male along in his quest to inseminate. The vagina is a remarkable organ in its own right, “full of glands and full of muscles and collagen, and changing constantly and fighting pathogens all the time,” she says. “It’s just a really amazing structure.”

To center females in genitalia studies, she knew she would need to go beyond ducks and start to open “the copulatory black box” of female genitalia more broadly. And, as she explored genitals, from the tiny, two-pronged snake penis to the spiraling bat vagina, she kept finding the same story: Males and females seemed to be co-evolving in a sexual arms race, resulting in elaborate sexual organs on both sides.

But conflict, it turned out, was hardly the only force shaping genitals.

For decades, biologists had noted a strange feature found in the reproductive tracts of marine mammals like dolphins, whales and porpoises: a series of fleshy lids, like a stack of funnels, leading up to the cervix. In the literature, they were known as “vaginal folds,” and were thought to have evolved to keep sperm-killing seawater out of the uterus. But to Dara Orbach, a Canadian PhD student who was studying the sexual anatomy of dolphins, that function didn’t explain the variation she was finding. After a chance pairing brought her together with Brennan in 2015, she brought her collection of frozen vaginas to Brennan’s lab to investigate.

What they found at first reminded them strongly of the duck story. In the harbor porpoise, for instance, the vagina spiraled like a corkscrew and had several folds blocking the path to the cervix. Porpoise penises, in turn, ended in a fleshy projection, like a finger, that seemed to have evolved to poke through the folds and reach the cervix. Just as in ducks, it seemed that males and females were both evolving specialized features in order to gain the evolutionary advantage during sex.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7f/df/7fdf5531-697d-4ded-abd4-4fe4bf32402c/gettyimages-1263017207_web.jpg)

Then, in the middle of their dolphin vagina dissections, the scientists stumbled across something else: a massive clitoris, partly enfolded in a wrinkled hood of skin. While the human clitoris has long been cast (erroneously) as small and hard to find, this one was virtually impossible to miss. When fully dissected out, it was larger than a tennis ball. “It was enormous,” Brennan says.

That dolphins would have a well-developed clitoris was no surprise. Brennan and Orbach both knew that these charismatic creatures engage in frequent sexual behavior for reasons like pleasure and social bonding. Females have been seen masturbating by rubbing their clitorises against sand, other dolphins’ snouts and objects on the sea floor. Yet while other scientists had guessed that the dolphin clitoris might be functional, no one had actually tried to figure out how it worked.

By dissecting 11 dolphin clitorises and running the samples through a micro CT scanner, the researchers uncovered a roughly triangular complex of tissues that sat just at the opening of the vagina—easily accessible to a penis, snout or fin. It was made up of two types of erectile tissue, both spongy and porous, allowing it to swell with arousal. These erectile bodies also grew and changed shape during puberty, suggesting they played an important role during adult sexual life. Strikingly large nerves, up to half a millimeter in diameter, ended in a web of sensitive nerve endings just beneath the skin.

In short, the dolphin clitoris looked a whole lot like the human clitoris, they reported in a paper published in January. And it probably worked like one, too. Brennan can’t say for certain that dolphins have orgasms, “But I’m pretty darn sure that sex feels good to them. Or at least that rubbing of the clitoris feels good,” she says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ae/c0/aec09048-dcaa-4b33-bce7-3032e1196bf8/slide3_web.jpg)

Before dolphins, even Brennan had not given much thought to role that non-reproductive sexual behavior might play in the evolution of genitals. In general, she subscribed to the tenets of classic Darwinian evolutionary thinking: “In my mind, everything ultimately has got to be reproductive,” she says. Perhaps, she thought, these behaviors might encourage future reproductive sex, eventually leading to more offspring. Or, a male’s ability to stimulate the clitoris might influence a female’s choice of mate.

Yet when it came to genital evolution, Darwin left much to be desired. The father of evolution generally eschewed talking about genitals, considering their main function to be fitting together mechanically, as a lock fits into a key. Moreover, he characterized female animals almost universally as chaste, modest and virtually devoid of sexual urges. In his lesser known writings, he described a world in which females honored their “husbands” and kept “marriage-vows.” Although he observed a few counter-examples—i.e. females with several “husbands” or those that seemed to pursue sex for pleasure—he steered clear of them, likely out of a sense of Victorian propriety.

To Darwin, males were the ones with the driving urge to engage in sexual behavior. The role of females, by contrast, was primarily to choose between competing males. “The males are almost always the wooers; and they alone are armed with special weapons for fighting with their rivals,” he wrote in his 1871 book Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. "They are generally stronger and larger than the females, and are endowed with the requisite qualities of courage and pugnacity.”

A century and a half later, Darwin’s influence still casts a long shadow over the field. In her frank exploration of animal vaginas, Brennan is beginning to challenge some the traces of prudery, male bias and lack of curiosity about female genitals that Darwin left behind. Yet she too had inherited some of that framework: Namely, she still thought about genitals mainly in conjunction with reproductive, heterosexual sex.

What she found in dolphins gave her pause. The substantial clitoris before her was a hint at something that seems obvious, but often isn’t: sex isn’t just for reproduction.

Today, we know that genitalia do far more than just fit together mechanically. They can also signal, symbolize and titillate—not just to a potential mate, but to other members of a group. In humans, dolphins and beyond, sexual behavior can be used to strengthen friendships and alliances, make gestures of dominance and submission, and as part of social negotiations like reconciliation and peacemaking, points out evolutionary biologist Joan Roughgarden, author of the 2004 book Evolution’s Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People.

These other uses of sex may be one reason that animal genitalia are so weird and wonderful beyond your standard vagina/penis combo. Consider the long, pendulous clitorises that dangle from female spider monkeys and are used to distribute scent; the notorious hyena clitoris, which is the same size as the male’s penis and used to urinate, copulate and give birth; and the showstopping genitalia that Darwin did briefly highlight in monkeys—the rainbow-hued genitals of vervets, drills and mandrills, and the red swellings of female macaques in estrus—that may connote social status and help troupes avoid conflict.

These diverse examples of “genital geometry” (Roughgarden’s term) serve a multitude of purposes beyond reproduction. “All our organs are multifunctional,” she points out. “Why shouldn’t the genitals be as well?”

Across the animal kingdom, same-sex behavior is widespread. In female-dominated species like bonobos, for instance, same-sex matings are at least as common as between-sex matings. Notably, female bonobos have massive, cantaloupe-sized labial swellings and prominent clitorises that can reach two and a half inches when erect. Some primatologists have gone so far as to suggest that the position of this remarkable clitoris—it’s in a frontal position, as in humans, and unlike in pigs and sheep, which have clitorises inside their vaginas—might have developed to facilitate same-sex genital rubbing.

“It does seem more logistically favorable, let’s say, for the kinds of sex they’re having,” says primatologist Amy Parish, a bonobo expert who was the first to describe bonobo societies as matriarchal. Primatologist Frans de Waal, too, has mused that “the frontal orientation of the bonobo vulva and clitoris strongly suggest that the female genitalia are adapted for this position.” Roughgarden has therefore coined this clitoral configuration the “Mark of Sappho.” And given that bonobos, like chimps, are some of our closest evolutionary cousins—they share 98.5 percent of our genes—she wonders why more scientists haven’t asked whether the same forces could be at play in humans.

These are questions that the current framework of sexual selection, with its simple assumptions about aggressive males and choosy females, renders unaskable. Darwin took for granted that the basic unit of nature was the female-male pairing, and that such pairings always led to reproduction. Therefore, the theory he came up with—coy females who pick among competing males—only explained a limited slice of sexual behavior. Those who followed in his footsteps similarly treated heterosexuality as the One True Sexuality, with all other configurations as either curiosities or exceptions.

The effects of this pigeonholing go beyond biology. The dismissal of homosexuality in animals, and the treatment of such animals as freaks or exceptions, helps reify negative attitudes toward sexual minorities in humans. Darwin’s theories are often misused today to promote myths about what human nature should and shouldn’t be. Roughgarden, a transgender woman who transitioned a few years before writing her book, could see the damage more clearly than most. Sexual selection theory “denies me my place in nature, squeezes me into a stereotype I can’t possibly live with—I’ve tried,” she writes in Evolution’s Rainbow.

Focusing solely on a few dramatic cases of sexual conflict—the “battle of the sexes” approach—obscures some of the other powerful forces that shape genitals. Doing so risks leaving out species in which the sexes cooperate and negotiate, including monogamous seabirds like albatrosses and penguins, and those in which homosexual bonds are as strong as heterosexual ones. In fact, it appears that the stunning variety of animal genitals are shaped by an equally stunning variety of driving forces: conflict, communication, and the pursuit of pleasure, to name a few.

And that, to both Brennan and Roughgarden, is freeing. “Biology need not limit our potential. Nature offers a smorgasbord of possibilities for how to live,” Roughgarden writes. Rather than chaste Victorian couples marching two by two up the ramp into Noah’s neat and tidy ark, “the living world is made of rainbows within rainbows within rainbows, in an endless progression.”

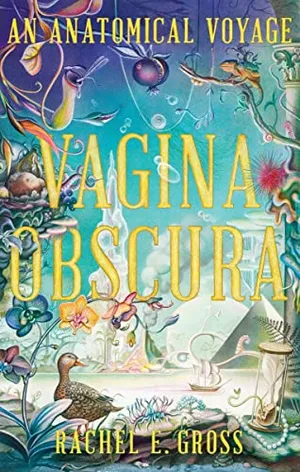

Adapted from Vagina Obscura: An Anatomical Voyage. Copyright © 2022 by Rachel E. Gross. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ce/97/ce9718f6-6031-43a2-b658-483157be2a76/veve_interior_chap03_f02_web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HeadshotGross_Web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HeadshotGross_Web.jpg)