Why the Leatherback Turtle Has a Skylight in its Head

How do animals with poor vision see in dark locales?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/80/1d80c265-14f3-4ccc-92b6-3f7fa8334c01/dec15_c05_phenom.jpg)

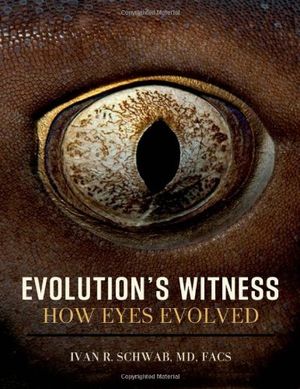

Close your eyes, and what do you see? Nothing, of course: The visual representation of your surroundings disappears. But you’re still receiving information from the ambient light passing through your eyelids. You can tell night from day and detect the flickering of shadows. That’s a poor substitute for color binocular vision for a primate, but for other animals, at other times, that kind of information has been crucial to survival, says ophthalmologist Ivan R. Schwab, author of Evolution’s Witness: How Eyes Evolved.

So a few animals retain primitive systems with the sole purpose of measuring ambient light—of which the most unusual is the leatherback sea turtle, one of the world’s largest reptiles. New research shows that the turtle has what British biologist John Davenport calls a “skylight” on the top of its skull, an unusually thin area of bone just beneath a spot of unpigmented skin that allows light to impinge directly on the brain’s pineal gland. With changes in long-wave light, Davenport proposes, the brain computes the “equilux,” the day (close to the equinox, but not necessarily coinciding) when sunset and sunrise are exactly 12 hours apart. More reliably than water temperature or light intensity, that’s the signal for turtles feeding in the North Atlantic to head south each fall.

In most vertebrates, humans included, the pineal regulates sleep and other cyclical activities in response to ambient light. A few species, mostly reptiles and amphibians, actually have a third eye on the top of their head to measure daylight, complete with a lens and retina—similar, but not identical, to the forward-facing eyes. Only leatherbacks, as far as we know, have the skylight.

Interestingly, there is a long philosophical and spiritual tradition of treating the pineal as a kind of parasensory organ, the mystical “third eye.” Descartes regarded it as the seat of the soul, because it had no symmetrical counterpart. Evolution has in fact equipped disparate parts of the body to respond to light, says Schwab; even humans have “photoreceptors in places you wouldn’t believe.”

There’s a sea snake with photoreceptors in its tail, to ensure that when it hides in a cave, it gets its whole body inside. The male genitalia of certain butterflies rely on light-sensing cells to make sure they aren’t ejaculating into the open air. And some corals cycle reproduction by the amount of blue light in the second full moon of springtime. “The whole Earth,” Schwab says, “has a heartbeat based on light.”

Evolution's Witness: How Eyes Evolved