Why Photographing Pandas Is More Challenging Than You Might Think

Photojournalist Ami Vitale describes her years of work capturing the lovable furballs

:focal(1014x721:1015x722)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/0f/df0fd33a-7c2b-45eb-a6d7-08132ab23eef/mm8391_15_08_29_1351-av.jpg)

On a drizzly day in China's Sichuan Province, Ami Vitale sat on a mountainside clad in a black and white panda suit, dappled with panda urine and feces. The photographer arrived as this wooded spot outside a panda enclosure in the Wolong Nature Reserve after a treacherous climb over steep, slippery terrain for the chance at catching a panda in the semi-wild.

She'd made the venture many times before, sometimes spending entire days in the hillsides without spotting even a flash of fuzz. But this day was different.

On the other side of the enclosure's electrified fence, a plump panda emerged from the trees—a 16-year-old female named Ye Ye. Vitale carefully threaded her hands through the fence, her assistant passing her the camera. The creature pushed itself up on its front legs, framed by the forest mist. Vitale snapped the picture, and then the panda disappeared.

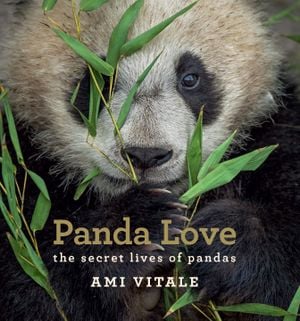

The photograph is one of the crowning jewels Vitale, a photographer for National Geographic magazine and Nikon ambassador, captured for her new book Panda Love: The Secret Lives of Pandas. Through its 159 pages, the book takes viewers on an exclusive look behind the scenes of China's panda breeding centers and captive release program, chronicling the loveable bears’ journey—from blind, hairless newborns no bigger than a stick of butter to full-furred adults who tip the scales at more than 300 pounds.

The project began in 2013 when Vitale was a member of a film crew photographing the release of Zhang Xiang, the first female captive panda to be unleashed into the wild. While watching the creature take its first hesitant steps, she knew she had something special.

"Immediately, I reached out to National Geographic," she says, recalling her excitement for the potential story. Though the organization initially turned her down, Vitale's tireless efforts to capture the journey of the creatures back into the wild eventually paid off, and the publication gave into the loveable balls of fluff.

“We think we know everything,” says Vitale. But as the ups and downs of the captive release program has shown, there is still much more to know about these ancient beasts.

Panda Love: The Secret Lives of Pandas

Panda Love is a collection of incredible images of these gentle giants. Ami Vitale's stunning photographs, taken on location in China, document the efforts to breed pandas and release them back into the wild.

Native to the forested mountains of central China, panda populations suffered in the late 20th century from poaching, deforestation and encroaching human development. However, with the backing of the Chinese government, the creatures are slowly multiplying in the rugged terrain. And now, as Vitale details in Panda Love, scientists are working to not only breed baby pandas, but release them back into the wild.

So far, researchers with the China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda have released seven captive bears. Five have survived. It's been a challenging road, but the hope is that these select few released can help bolster wild populations, which stand at fewer than 2,000 individuals.

Plenty of Vitale's images revel in the adorableness of the tiny floofs—their roly-poly nature, their jet-black ear fluffs and their expressive black eye patches. One image shows a mischievous youngster attempting escape from its wicker napping basket. Another captures a baby mid nap, its face planted flat against a tree and fuzzy limbs hanging limp.

But Vitale's images also reveal the tireless work of pandas’ caretakers. Though their jobs may seem enviable, it’s a surprisingly challenging position. "[The keepers] work these 24-hour shifts...They're constantly going around and weighing them, and feeding them, and cleaning them," she says. They are even tasked with rubbing the pandas’ bellies to stimulate their digestion and ensure they defecate on a regular basis.

Breeding offers even more challenges. Many undergo artificial insemination, but the creatures' fertility window is narrow. Endocrinologists monitor hormones in the panda urine to determine when they enter estrus, which happens once a year for just 24 to 72 hours.

"But then you see this really sweet, soft side," says Vitale. Some of the most striking images in the book capture intimate moments between panda and person—a post-exam snuggle, a loving gaze. "They spend more time with these babies than their own children," she says, "so they fall in love with them."

Vitale has traveled the world for her work, capturing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the human costs of coal, the death of the world's last male Northern White Rhino, and more. So she didn't think pandas would pose a major challenge. "How hard can it be to photograph a panda, right?" she jokes.

It turns out, it's pretty hard. "It was actually, truly one of the hardest stories I've ever covered," she says.

"These are million-dollar bears," Vitale emphasizes several times in conversation, so there is great caution taken with the fuzz-faced creatures. Those working with the prized bears bound for the wild—Vitale included—don panda suits that both look and smell like their tiny charges, preventing them from habituating to humans. (Not all captive release programs use the suits: in a new effort at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, keepers forego the costumes in an effort to build trust with the bears.)

Then there's Vitale's own safety. She emphasizes that though they are cute, pandas are still bears. "After six months, they're really dangerous," she says. "They've got teeth and claws." Vitale adds she still has scars from baby pandas attempting to scale her legs during a VR film shoot.

Once the creatures no longer require round the clock care, they undergo a series of tests in increasingly large enclosures to encourage them to find the wild within. But that also means they have an increasing number of spots to hide away from an eager photographer.

"It was a lot of 'Zen' time," says Vitale, who describes herself as a "wound-up, wired" person, not necessarily disposed to spending days lying in wait.

"Surreal" is a common word she used to describe the experience. Oftentimes she found herself stepping back and marveling at her situation. "What am I doing?" she recalls wondering. "I'm sitting there in this forest in a panda costume, just waiting for hours for something to happen," she says with a hearty laugh. "It was ridiculous."

But then there were those special moments—like catching Ye Ye in the forest—that made the project worth the effort. "It was really humbling," Vitale says of the project. "It was not easy, but it also, at the end, gave me so much hope."

Her goal is to inspire this same feeling in others. With so much attention on the panda, their outlook is bright. But she adds, "the challenges are not over."

With climate change and habitat loss many creatures—pandas included—face uncertain futures. "Everything is linked together," says Vitale. "The panda is kind of an ambassador for all these other species that live with them in the forest."

"If you love the panda, you have to love all the other species because we need them to coexist," she says. And after paging through the many images of the floppy fuzz balls in Vitale's new book, it's nearly impossible not to fall in love.

*Photos are reprinted from Vitale's book Panda Love: The Secret Lives of Pandas, published by Hardie Grant.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)