Why PTSD May Plague Many Hospitalized Covid-19 Survivors

Scientists warn about the likelihood of post-traumatic stress disorder for patients discharged from the intensive care unit

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c8/51/c851d637-b814-4a4d-8dfa-9083a90ac30a/gettyimages-1230533927.jpg)

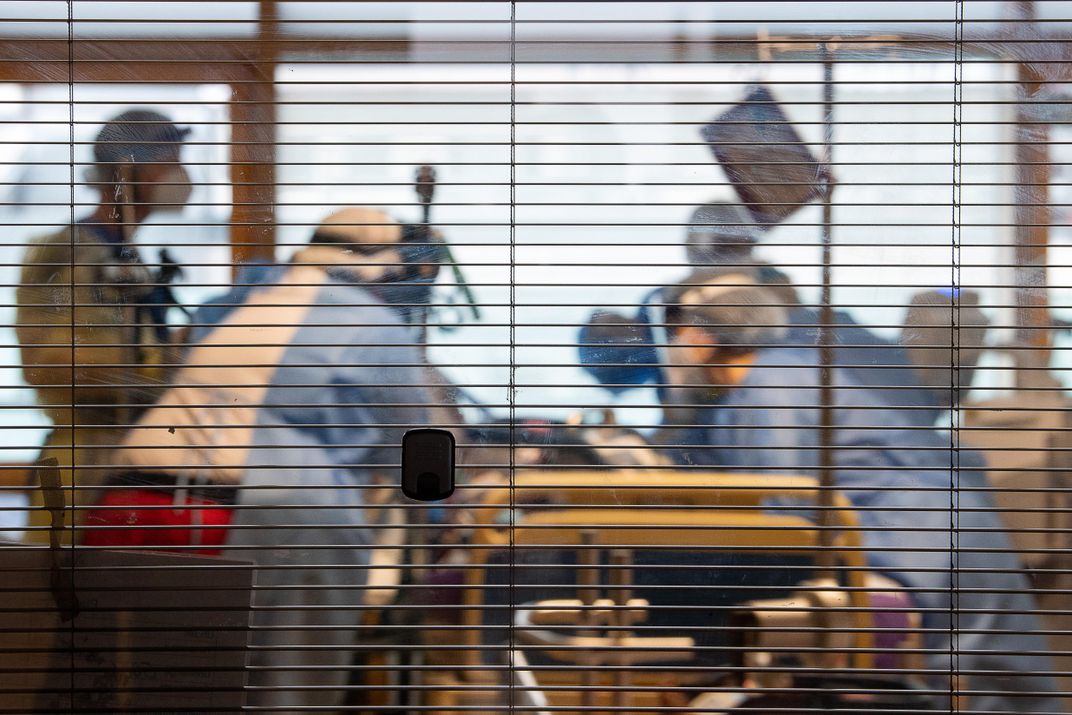

While neuropsychologists Erin Kaseda and Andrew Levine were researching the possibility of hospitalized Covid-19 patients developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), they heard reports of patients experiencing vivid hallucinations. Restrained by ventilators and catheters, delirious from medication and sedatives and confused by the changing cast of medical professionals cycling through the ward, intensive care unit (ICU) patients are especially prone to trauma. For Covid-19 ICU patients, a combination of factors, including side effects of medication, oxygenation issues and possibly the virus itself, can cause delirium and semi-consciousness during their hospital stay. Kaseda says as these patients slip in and out of consciousness, they may visualize doctors wheeling their bodies to a morgue or see violent imagery of their families dying. Such instances, though imagined, can cause trauma that may lead to PTSD in patients long after they have physically recovered from Covid-19.

In addition to hallucinations during hospitalization, some Covid-19 survivors describe a persistent feeling of “brain fog” for weeks or months after recovery. “Brain fog” is an imprecise term for memory loss, confusion or mental fuzziness commonly associated with anxiety, depression or significant stress. As scientists grappled with whether such brain damage could be permanent, Kaseda and Levine warn that cognitive issues often attributed to “brain fog” may, in fact, be signs of PTSD. Kaseda, a graduate student at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science in Chicago, and Levine, a professor of neurology at the University of California Los Angeles, co-authored a study published in Clinical Neuropsychologists in October intended to alert neuropsychologists to the possibility of PTSD as a treatable diagnosis for those who survived severe illness from Covid-19.

“You have this unknown illness: there’s no cure for it, there’s high mortality, you’re separated from your family, you’re alone,” Kaseda says. “If you’re hospitalized that means the illness is pretty severe, so there’s this absolute fear of death that even if you aren’t having the delirium or the other kind of atypical experiences, just the fear of death could absolutely constitute a trauma.”

How Post-Traumatic Stress Develops in Covid-19 Patients

PTSD arises from experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event, specifically exposure to actual or threatened death and serious injury, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

Historically associated with combat veterans, PTSD was called “shell shock” or “combat fatigue” before it became a named disorder in 1980. But in 2013, the definition of PTSD broadened to include more common place traumatic experiences.

Psychiatrists are now increasingly seeing PTSD develop after traumatic stays in the ICU for any health problem, but researchers are still unsure of the scope of this issue. A paper published in 2019 in the Lancet reports that roughly a quarter of people admitted to the ICU for any health issue will develop PTSD. Another study found that between 10 and 50 percent of people develop PTSD after ICU discharge, and, in a 2016 study of 255 ICU survivors, one in ten reported PTSD within one year after discharge.

Before hospitalized patients are diagnosed with PTSD, their symptoms may be described as post intensive care syndrome (PICS). PICS can manifest as a number of physical, cognitive and mental health problems that a patient may experience in the weeks, months or years after being discharged from the ICU.

Kristina Pecora, a clinical psychologist at NVisionYou in Chicago, sees a variety of patients, including frontline medical professionals and Covid-19 survivors. Pecora was a contributing author of a brief submitted to the American Psychological Association in May describing the signs of PICS and urging psychologists to prioritize screening and referral for behavioral health problems related to hospitalization for Covid-19. At that time, some of Pecora’s patients showed signs of the lingering trauma typical of PICS within six months of their ICU discharge. Because a PTSD diagnosis can often only be made after this period, it was too early to tell then whether her patients’ PICS symptoms could be classified as PTSD. But the impact of the virus on their psychiatric health was clearly substantial.

“It becomes this gradual realization that what they’re experiencing is persisting week after week and ‘oh my goodness, this is a longer-term experience than what we thought it would be,’” Pecora says.

A “Delirium Factory”

One major factor in whether patients develop long-term psychological effects after ICU discharge is whether or not they experience delirium during their stay. Delirium is a state of severe confusion and disorientation, often characterized by poor memory, nonsensical speech, hallucinations and paranoia. Patients who experience delirium may not be able to differentiate between real and imagined humans or events.

Side effects of sedatives, prolonged ventilation and immobilization are common factors that put many ICU patients at-risk for delirium. A study from 2017 found that up to 80 percent of mechanically ventilated people enter a hallucinogenic state known as ICU delirium.

Add isolation and the unknown cognitive effects of the virus to the mix and an ICU becomes a “delirium factory” for Covid-19 patients, as authors of a study published in BMC Critical Care in April wrote. In a different study from June, which has not yet undergone peer review, 74 percent of Covid-19 patients admitted to the ICU reported experiencing delirium that lasted for a week.

“Any time anyone is in a fearful experience and they’re isolated—they can’t have anybody in their rooms—they wake up in a strange experience or a strange place, or they know already while they’re in there that they can’t have anyone hold them or be with them. All of that is going to attribute to the emotional impact,” Pecora says.

Such intense visions and confusion about the reality of hospitalization can be especially scarring, leaving patients with intrusive thoughts, flashbacks and vivid nightmares. If such responses persist for more than one month and cause functional impairment or distress, it may be diagnosed as PTSD.

To help reduce ICU-related trauma, doctors may keep a log of the patient’s treatment to help jog their memory once they have been discharged. Having a record of the real sequence of events can help a patient feel grounded if they have hallucinations and flashbacks to their hospitalization experience.

But even for patients experiencing Covid-19 symptoms that aren’t severe enough to warrant a hospital visit, the fear of death and isolation from loved ones can be sufficiently distressing to cause lasting trauma. They may experience shortness of breath and worsening symptoms, fueling a fear that their condition will quickly deteriorate. For several days, they may avoid sleeping for fear of dying.

“Some people are more resilient in the face of that sort of trauma and I would not expect them to develop lasting psychological symptoms associated with PTSD,” says Levine. “But other people are less resilient and more vulnerable to that.”

Learning from SARS and MERS

Covid-19 isn’t the first epidemic to cause a domino effect of persisting psychiatric health problems across a population. The current pandemic has been compared to the severe adult respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak in 2014 in Saudi Arabia—both diseases caused by coronaviruses. In an analysis of international studies from the SARS and MERS outbreaks, researchers found that among recovered patients, the prevalence of PTSD was 32.2 percent, depression was 14.9 percent and anxiety disorders was 14.8 percent.

Much like those who fall ill with Covid-19, some patients sick with SARS and MERS developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which causes patients to experience similar feelings of suffocation and delirium during treatment in the ICU. Levine says that many of the people who developed PTSD during the SARS and MERS epidemics were hospitalized.

By contrast, Levine anticipates Covid-19 survivors with relatively mild symptoms may experience traumatic stress too, due to an inundation of distressing images, frightening media reports and a higher expectation of death.

For those who recover from Covid-19, their trauma may be compounded by social isolation and physical distancing practices after they are discharged from the hospital. “If you did experience a trauma, it can make it so much harder to naturally recover from that when you lack the social support from family and friends that maybe would be possible to receive in different circumstances,” Kaseda says.

Screening for PTSD in Covid-19 survivors soon after recuperation is important, Kaseda says, so that patients can receive the right treatment for their cognitive difficulties. If PTSD is treated early on, it can speed a person’s entire Covid-19 recovery.

“If we can treat the PTSD, we can see what parts of the cognition get better,” Kaseda says. “And that will give us more confidence that if problems persist even after the PTSD is alleviated, that there is something more organic going on in the brain.”

A Constantly Shifting Landscape

As more information about the traumatic effects of Covid-19 treatments become clear, neuropsychiatrists and psychologists can shift their approach to dealing with the cognitive effects of Covid-19. Scientists don’t yet have a full grasp on how Covid-19 directly affects the brain. But by maintaining an awareness of and treating PTSD in Covid-19 patients, psychiatrists and clinicians may be able to minimize some cognitive problems and focus on the unknowns.

“Part of the problem is that all of this is so new,” Pecora says. “We’ve only really been seeing this for six or seven months now and the amount of information we have gleaned, both in the medical and the psychological worlds has increased so exponentially that we have a hard time keeping up with what were supposed to be looking out for.”

Deeper understanding of which symptoms arise from brain damage and which are more psychological will help both clinicians and psychologists address patients’ needs in their practice.

“The social and emotional impact of Covid-19 hasn’t even dawned on us yet. We clinicians and doctors are certainly trying to prepare for it.,” Pecora says. “But the way this has impacted society and mental health is going to be so vast.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)