Why Is Washing Your Hands So Important, Anyway?

A dive into the science behind why hand-washing and alcohol-based hand sanitizer work so well

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3f/01/3f01bbdb-480f-4b1a-b808-76811e4c13b6/gettyimages-1182622704.jpg)

Avoid close contact with sick patients. Stay home if you’re feeling unwell. Scrub your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds and for goodness’ sake, stop touching your face.

By now, you’ve probably heard or seen the advice from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for staving off COVID-19, the viral epidemic ricocheting across the globe. Most cases of the disease are mild, triggering cold-like symptoms including fever, fatigue, dry cough and shortness of breath. The death rate appears to be low—about two or three percent, perhaps much less. But the virus responsible, called SARS-CoV-2, is a fearsomely fast spreader, hopping from person to person through the droplets produced by sneezes and coughs. Since COVID-19 was first detected in China’s Hubei province in December 2019, nearly 100,000 confirmed cases have been reported worldwide, with many more to come.

To curb the virus’ spread, experts stress the importance of hand hygiene: keeping your hands clean by regularly lathering up with soap and water, or, as a solid second choice, thoroughly rubbing them down with an alcohol-based sanitizer. That might sound like simple, even inconsequential advice. But such commonplace practices can be surprisingly powerful weapons in the war against infectious disease.

“[Washing your hands] is one of the most important ways to interrupt transmission of viruses or other pathogens,” says Sallie Permar, a physician and infectious disease researcher at Duke University. “It can have a major impact on an outbreak.”

How to Destroy a Virus

In the strictest sense of the word, viruses aren’t technically alive. Unlike most other microbes, which can grow and reproduce on their own, viruses must invade a host such as a human cell to manufacture more of themselves. Without a living organism to hijack, viruses can’t cause illness. Yet viral particles are hardy enough to remain active for a while outside of the host, with some staying infectious for hours, days or weeks. For this reason, viruses can easily spread unnoticed, especially when infected individuals don’t always exhibit symptoms—as appears to be the case with COVID-19.

Researchers are still nailing down the details of exactly how SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted and how resilient it is outside the body. Because the virus seems to hang out in mucus and other airway fluids, it almost certainly spreads when infected individuals cough or sneeze. Released into the air, infectious droplets can land on another person or a frequently touched surface like a doorknob, shopping cart or subway seat. The virus can also transfer through handshakes after someone carrying the virus sneezes or coughs into their hand.

After that, it’s a short trip for the virus from hand to head. Researchers estimate that, on average, humans touch their faces upwards of 20 times an hour, with about 44 percent of these encounters involving eyes, mouths and noses—some of the quickest entry points into the body’s interior.

Breaking this chain of transmission can help stem the spread of disease, says Chidiebere Akusobi, an infectious disease researcher at Harvard’s School of Public Health. Sneezing or coughing into your elbow can keep mucus off your mitts; noticing when your hand drifts towards your face can help you reduce the habit.

All this public-health-minded advice boils down to a game of keep away. To actually infect a person, viruses must first get inside the body, where they can infect living cells—so if one lands on your hands, the best next move is to remove or destroy it.

The Science Behind Hand-Washing

The most important step to curbing infection may be hand-washing, especially before eating food, after using the bathroom and after caring for someone with symptoms. “It’s simply the best method to limit transmission,” says Kellie Jurado, a virologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. “You can prevent yourself from being infected as well as transmitting to others.”

According to the CDC, you should wet your hands—front and back—with clean, running water; lather up with soap, paying mind to the easily-forgotten spaces between your fingers and beneath your nails; scrub for at least 20 seconds; then rinse and dry. (Pro tip: If counting bores you or you’re sick of the birthday song, try the chorus of these popular songs to keep track.)

Done properly, this process accomplishes several virus-taming tasks. First, the potent trifecta of lathering, scrubbing and rinsing “physically removes pathogens from your skin,” says Shirlee Wohl, a virologist and epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University.

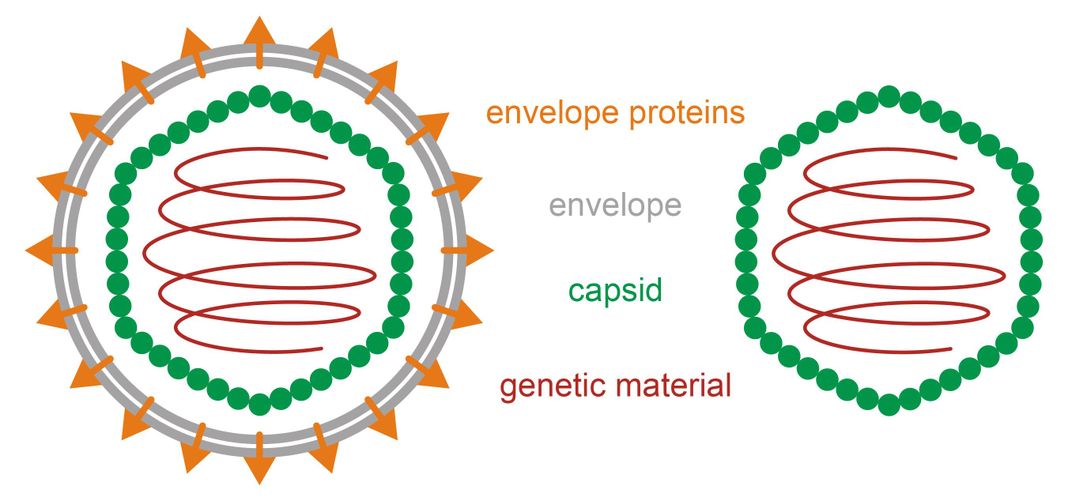

In many ways, soap molecules are ideal for the task at hand. Soap can incapacitate SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses that have an outer coating called an envelope, which helps the pathogens latch onto and invade new cells. Viral envelopes and soap molecules both contain fatty substances that tend to interact with each other when placed in close proximity, breaking up the envelopes and incapacitating the pathogen. “Basically, the viruses become unable to infect a human cell,” Permar says.

Alcohol-based hand sanitizers also target these vulnerable viral envelopes, but in a slightly different way. While soap physically dismantles the envelope using brute force, alcohol changes the envelope’s chemical properties, making it less stable and more permeable to the outside world, says Benhur Lee, a microbiologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. (Note that “alcohol” here means a chemical like ethanol or isopropyl alcohol—not a beverage like vodka, which contains only some ethanol.)

Alcohol also can penetrate deep into the pathogen’s interior, wreaking havoc on proteins throughout the virus. (Importantly, not all viruses come with outer envelopes. Those that don’t, like the viruses that cause HPV and polio, won’t be susceptible to soap, and to some extent alcohol, in the same way.)

Hand sanitizers made without alcohol—like some marketed as “baby-safe” or “natural”—won’t have the same effect. The CDC recommends searching for a product with at least 60 percent alcohol content—the minimum concentration found to be effective in past studies. (Some water is necessary to unravel the pathogen’s proteins, so 100 percent alcohol isn’t a good option.)

As with hand-washing, timing matters with sanitizers. After squirting a dollop onto your palm, rub it all over your hands, front and back, until they’re completely dry—without wiping them off on a towel, which could keep the sanitizer from finishing its job, Jurado says.,

But hand sanitizers come with drawbacks. For most people, using these products is less intuitive than hand-washing, and the CDC notes that many people don’t follow the instructions for proper application. Hand sanitizers also don’t jettison microbes off skin like soap, which is formulated to lift oily schmutz off surfaces, Akusobi says.

“Soap emulsifies things like dirt really well,” he says. “When you have a dirty plate, you don’t want to use alcohol—that would help sterilize it, but not clean it.”

Similarly, anytime the grit is visible on your hands, don’t grab the hand sanitizer; only a full 20 seconds (or more) of scrubbing with soapy water will do. All told, hand sanitizer “should not be considered a replacement for soap and water,” Lee says. “If I have access to soap and water, I will use it.”

Too Much of a Good Thing?

Technically, it is possible to overdo it with both hand-washing and hand sanitizing, Akusobi says. “If your skin is chronically dry and cracking, that’s no good. You could be exposing yourself to other infections,” he says. But “it would take a lot to get to that point.”

In recent weeks, hand sanitizers have been flying off the shelves, leading to shortages and even prompting some retailers to ration their supplies. Some people have begun brewing up hand sanitizers at home based on online recipes.

Many caution against this DIY approach, as the end products can’t be quality controlled for effectiveness, uniformity or safety, says Eric Rubin, an infectious disease researcher at Harvard’s School of Public Health. “On average, one would imagine that [a homemade sanitizer] would not work as well, so it would be a mistake to rely on it,” he says.

As more information on SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 emerges, experts stress the importance of awareness. Even as the news changes and evolves, people’s vigilance shouldn’t.

“Do the small things you need to do to physically and mentally prepare for what’s next,” Wohl says. “But don’t panic. That never helps anybody.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)