Neuroscientists Unlock the Secrets of Memory Champions

Boosting your ability to remember lists, from facts to faces, is a matter of retraining your brain

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/6c/8d6cced9-9560-4dc5-b9e3-9ac99a60d1a2/anhkxm_2.jpg)

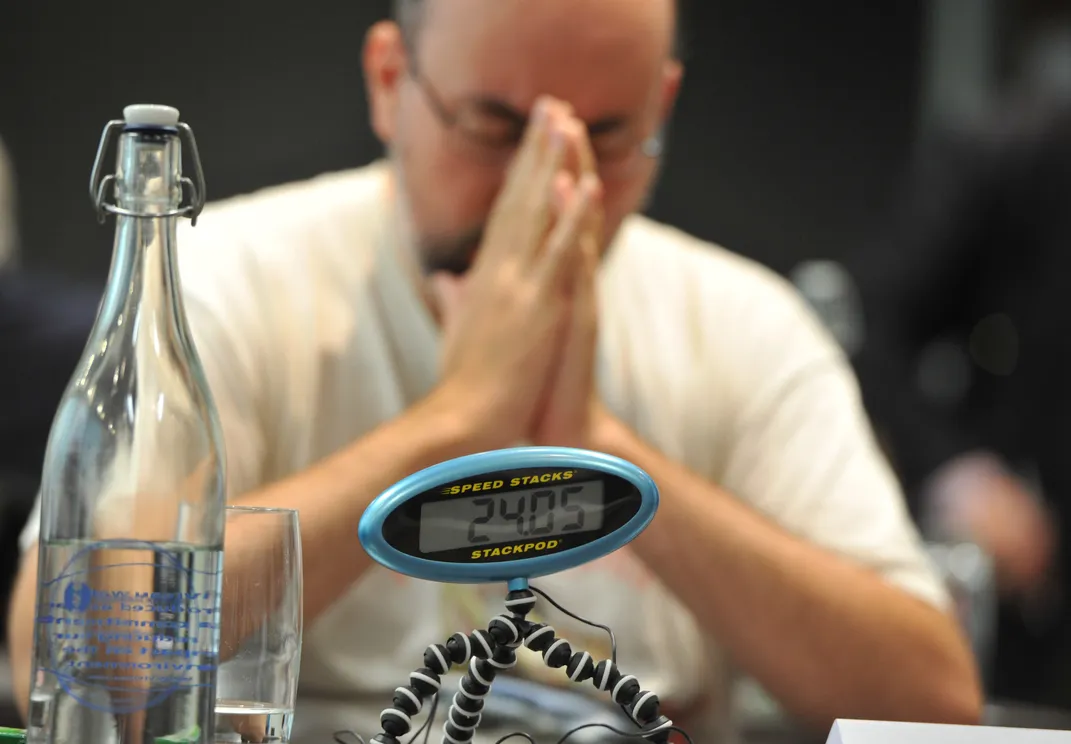

In five minutes, 32-year-old Boris Konrad can memorize more than 100 random dates and events. After 30 seconds, he can tell you the order of an entire deck of cards. During the 2009 German Memory Championships, Konrad memorized 195 names and faces in 15 minutes—a feat that won him a gold medal. What's it like to be born with a brain capable of such incredible feats? He says he wouldn't know.

That’s because Konrad’s remarkable talent wasn’t innate; it was learned. “I started with a normal memory and just trained myself,” he recalls. Konrad credits his subsequent success in the world of competitive memory sports to years of practice and employing memorization strategies like the ancient "Memory Palace" technique. In fact, Konrad says, any average forgetful Joe can use these same strategies to train their brains like a memory champion.

The idea that simple memory techniques can result in significant, lasting gains in the ability to memorize faces and lists may at first sound hard to believe. But a new brain imaging study that Konrad co-authored lends scientific support to the claim. Konrad, a world-ranked memory champ who has trained many memories himself over the years, teamed up with Martin Dresler, a cognitive neuroscientist at Radboud University Medical Center in The Netherlands, to delve deeper into the neuroscience behind these tried-and-true memory-boosting techniques.

For the first time, the researchers used brain imaging to reveal that practicing these kinds of mnemonic techniques can actually alter crucial connections to make memorizers’ brains more resemble those of the world's memory champions. The results, published March 8 in the journal Neuron, shed some light on why these techniques have such a strong track record.

In the study, 23 participants who spent 30 minutes a day training their memories more than doubled their abilities to remember lists in just 40 days. (For example, those who could remember an average of 26 words from a list were able to recall 62.) Perhaps best of all, it appears that these gains aren't short-lived and don't require continued training: Researchers invited the group back after four months and found that their memory performance was still high, even though they hadn't been training at all.

In recent years, Dresler and colleagues investigated 35 of those memory champions and found they share something surprising in common. “Without exception, all of them tell us that they had a pretty normal memory before they learned of mnemonic strategies and started training in them,” he says. “Also, without exception, they say the method of loci is the most important strategy.”

The “method of loci”—sometimes called the Memory Palace—is a systematic memory technique that dates back to the days of ancient Greece. The system remained prevalent through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Educators used it as did orators, the better to remember aspects of long speeches of a more attentive age.

How does it work? Users create a visual map in the mind, like a familiar house or walking route, and then connect memorable, multisensory images to each location to retrieve them later. To remember a string of unrelated words, for example, Konrad might map the body starting with the feet, then moving to the knees, and so on. He then "places" two words at each location to memorize a list of unconnected terms.

For example, if the words for feet are "moss" and "cow," he might picture walking on a mossy field, getting bits of moss stuck on his socks and watching a smelly cow grazing on that moss. If the next location, the knees, is assigned the words "queen and bell" Konrad then imagines walking off the moss to sit on a stump. Suddenly the Queen of England promptly appears to sit on his knee. She then pulls from her pocket a bell which she beings to ring loudly.

Absurd? Of course. But memorable, Konrad, stresses. And that's the point. The system takes advantage of the memory's strong ability to store spatial locations and make associations. (See him walk though this and other examples in a TED talk.)

Konrad wasn't surprised that the study results showed dramatic improvements for all the subjects who put in the training time. “As it was my training paradigm we used, and I have trained many groups with it before, I at least knew it does work—and work well," he says. "So I also had the hypothesis it would have a comparable effect in the brain as within the athletes." Moreover, previous studies have chronicled the success of these kinds of memory techniques.

But until now, researchers didn’t understand how they worked in the brain. So for this study, researchers decided to scan the brains of memorizers as they practiced tried-and-true memory techniques, to see how their brains changed in response to their training. They used fMRI scans to look at the brains of 23 memory competitors and 51 people who resembled them in age, health and intelligence but had only typical memory.

As far as brain structure and anatomy were concerned, the brains all looked basically the same, offering no clue to the memory mojo that some of them enjoyed. But when the average memory people divided into three groups and began to train their memories, something changed.

The control group that received no memory training, unsurprisingly, showed little to no gain in memory performance. The second group practiced memorizing challenges similar to the way one might when playing Concentration, finding and remembering locations of matching cards from a deck spread across a table. They'd recalled 26 to 30 words, on average, before training. After 40 days, they'd upped that by an average of 11 words.

But those who trained using the method of loci received the real boost. That third group used a public platform called Memocamp, which Dresler chose because it's used by many champion memorizers. They more than doubled their initial memorizing ability during the 40 days.

Not only had the group's memory abilities changed—so had their brains. The fMRI images mapped blood flow and brain activity for some 2,500 different connections, including 25 that stood out as most linked with the greater memory skills displayed by the competitors. Post-training scans showed that this group's patterns of connectivity had begun to rearrange themselves in a way that the memory champions functioned, but the others groups did not.

“I think the most interesting part of our study is the comparison of these behavioral memory increases with what happens on the neurobiological level,” he says. “By training this method that all the memory champions use, your changeable brain connectivity patterns develop in the direction of the world's best memory champions.”

That result also says something about the origins of the champions' memorizing talent, says Umeå University neuroscientist Lars Nyberg, who wasn't involved in the study. “The finding that training can shape the brain in a similar way in non-experts supports the view that expert performance is really the result of training—not any particular abilities," he says.

Being able to memorize long lists of names and faces might seem like a novelty, but it can have some real world applications. Users might memorize grocery lists, for example, or learn to match faces and names, which is an event at memory competitions. But those hoping that practice will help them never miss an appointment should think twice.

Monica Melby-Lervåg, at the University of Oslo, has explored how working memory training might help the cognitive development of children and adults. So far, she notes, this kind of training hasn't been shown to impact more general cognitive or memory function. “The more critical thing here is how this transfer to tasks relevant for daily life (i.e. beyond a technical memory test), and the prospects for this do not look very good based on many previous studies,” she notes.

Indeed, even the superstars of memory sport admit to having the same day-to-day brain cramps as the rest of us, from forgetting their car keys to leaving their wallet at a restaurant. So far, it appears that if memory trainers like the method of loci are valuable tools, they only work for memorizing lists and only when people actively use them.

“You do have to apply this for it to work,” says Dresler. “Your memory doesn't just get better in general. So when you don't apply this strategy, probably your memory is only as good as it was before.”