Wild Goose Chase

How one man’s obsession saved an “extinct” species

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/aleutian-cackling-goose-631.jpg)

Bob “Sea Otter” Jones, alone in a wooden dory, traveled to an unexplored island in the Aleutian chain in the summer of 1962. Set against the sea, he was as inconsequential as a jellyfish. He rolled over waves and dodged sea lions as he pushed his way through dense fogs. On most days of his life he saw more birds than people, which suited him fine. On this day, he pointed his boat toward Buldir Island. The approach was treacherous. The rocky shore offered no soft landing, but plenty of hard ones. Jones was as close to Japan as to Alaska—far from any home. He had come to the island chasing wild geese. Really.

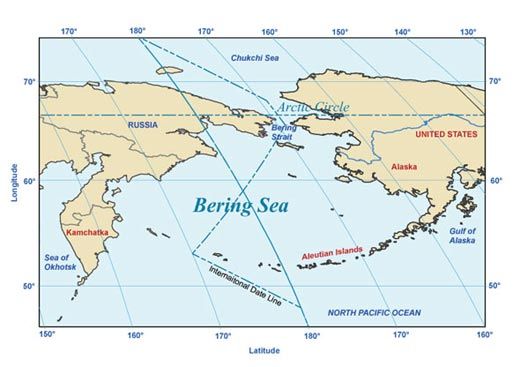

The Aleutian Islands are the wildest land in North America. Even today they are scarcely known. At 1200 miles in length, the chain is too large for the evening weather maps. Cool and warm waters meet here and trigger a great, green upwelling of life. Bountiful plankton feed fish. And each year those fish feed seabirds, birds once (and sometimes still) as dense and dark as dump flies.

The Aleutian cackling goose, Branta hutchinsii leucopareia, evolved among these islands recently, perhaps after the last ice age 10,000 years ago. It was once a common bird as far west as Japan. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, when fur trappers were looking for places to leave foxes—so that the foxes might feed, breed, produce fur and be easily captured later—goose nesting grounds seemed ideal. The foxes devoured eggs and goslings, which couldn’t fly to escape. Even the adult geese, with their long takeoffs, were sometimes victims. Goose populations crashed. By 1940 the Aleutian cackling goose was extinct.

By the time Sea Otter Jones began to work on eradicating foxes in the Aleutians, islands once green with guano-fertilized grass had turned brown. The fox had won and the cackling goose and many other island-nesting bird species had lost. But Jones was not convinced the goose was gone. He had seen many rare and strange things in his travels among the fog-draped islands. As he traveled, he searched for some sign of hope, a dove perhaps, or better yet a goose. And then it happened. Jones and some colleagues were on Amchitka Island. They looked up and saw what Jones thought were Aleutian cackling geese flying west. They were elated, but joy would mingle with doubt. The birds could have been another species flying off track. Hope can turn pyrite into gold and even more easily one kind of goose into another.

Jones wanted to chase those geese, and he focused his search on Buldir Island, 200 miles from the next island or other scrap of land. A Coast Guard vessel dropped his dory off near the shore. Had he finally arrived at a pristine island, one unspoiled by trappers or foxes? As he guided his boat along the rocks, he saw sea otters with pups, colonies of tufted puffins, horned puffins, murres, black-legged kittiwakes, glaucous-winged gulls, ancient murrelets, winter wrens, song sparrows, rosy finches, pelagic cormorants, common eiders, one pair of bald eagles and thousands of Steller sea lions hauled out on the shore. All told there were more than three million birds, a city of birds, stinking, calling, crying birds. And then he saw them, his reward for his years of hope, “flying off the high steep sea cliffs”: 56 Aleutian cackling geese. He could hear their squeaking cackles, a sound unheard by humans for decades.

Jones’ discovery paved the way for a phoenix-like recovery. The goose was one of the first animals declared an endangered species, in 1967, and what remained was to rescue it. Jones collected goslings from nests for captive rearing and breeding. Meanwhile he continued to remove foxes from other islands. On Amchitka Island, where he had worked so long, no foxes remained—no footprints, scat or trace. He had readied the land. The biologists that Jones had trained and inspired attempted to reintroduce the geese to Amchitka. At first the geese didn’t take, so they were reintroduced again on more western islands and then again and again. Eventually they survived. Two hundred became four hundred, four hundred became eight hundred, eight hundred became even more.

In October my family and I visited my sister in Homer, Alaska, at the civilized edge of the Aleutian Islands, not far from where Jones sometimes launched his boat. We went to the beach one morning to walk along the ocean. We had coffees and hot cocoas and each others’ companionship and were, quite simply, comfortable. We stood talking as the waves came in over surf-smoothed rocks. We were all keeping an eye on the water for sea otters. The mere possibility of sighting otters was exciting. We did not even dream of spotting Jones’ geese here, hundreds of miles from Buldir Island. The geese were still, in my mind, more allegory than real bird. And then they appeared—five rowdy geese flying over the water in a V, one in front, two on either side. They didn’t cackle, but we could hear their wings, almost clumsy, grabbing at the cold air. They were alive and above us and as wild as they had ever been. What took Jones so much work to see is now anyone’s to enjoy. I could not have been more grateful for Jones, for his birds and for all that remains possible and alive in this world.

Today there are tens of thousands of Aleutian cackling geese, and 40 islands have been cleared of foxes. The geese spread over the foxless islands like the tide coming back in over rocks. In 2001, the Aleutian cackling goose was one of the only animals to be taken off the Endangered Species List. The islands from which foxes have been removed grow verdant again with plants nourished by excrement of animal life.

There are just a handful of success stories in conservation. These stories often share two attributes: the problem the species faces is understood and fixable, and some individual human is dedicated beyond reason to the rescue of the species. For the Aleutian cackling geese, the problem was the fox and the human was Jones.

The world has many rare and dwindling species. There will be other conservation crises in the islands. Some seabirds are declining mysteriously. Numbers of cormorants, Larus gulls, pigeon guillemots, horned puffins and black-legged kittiwakes have all decreased since the early 1980s. Nor, unfortunately, are the species of the Aleutian Islands unique in this regard. Some declining species have champions (see, for example, the Oregon and California and then each summer they head home again to the islands. There, in the Aleutians, eggs hatch into goslings, goslings learn to fly, and as winter comes they all take off, cackling, and announcing their place, as Mary Oliver has written, in the family of things.

Rob Dunn is a biologist at North Carolina State University. His book "Every Living Thing: Man's Obsessive Quest to Catalog Life, from Nanobacteria to New Monkeys" comes out in January. Find more on Dunn's work at http://www4.ncsu.edu/~rrdunn/.