Wild Things: Life as We Know It

From zombie caterpillars to basking sharks at sea

Die, Zombie, Die

The strange thing about a Brazilian wasp isn't that it injects its eggs into a caterpillar, where they turn into larvae, feed on the host's bodily fluids and hatch through its skin. A lot of parasites do that. What's unique, according to a study from the Netherlands, is that the larvae compel the dying caterpillar to swing its head violently after they emerge, possibly scaring predatory bugs away.

Climate Control

Even if it's cold or hot outside, it's just right inside leaves. A University of Pennsylvania study of oxygen atoms in 39 tree species, growing from northern Canada to Puerto Rico, suggests that leaves have an internal thermostat set at 70.5 degrees Fahrenheit. They may alter evaporation rates or their angle to the sun to stay near this temperature, which is ideal for photosynthesis.

Observed

Name: Arthroleptidae, a family of frogs living in sub-Saharan Africa.

At Rest: These frogs have smooth and shiny hind feet.

In Distress: They sprout claws from beneath the skin on their toes.

Under Scrutiny: No other vertebrate has claws like these, according to a new study from Harvard. They are composed not of keratin, the stuff of fingernails, but of bone. And they have to pierce their owner's skin before they can pierce anything else. The researchers figured out the anatomy that allows the claws to spring forth, but they could only speculate about how the claws retract—and how this frog's skin heals after it uses its claws.

Wide Open

Basking sharks are typically found in coastal waters, where they meander so slowly with their mouths agape feeding on plankton that they appear to be just basking in the sun. But scientists who tagged two sharks near the Isle of Man found that one swam to Newfoundland, traveling almost 6,000 miles and diving deeper than 4,000 feet. The shark may have been seeking food. So much for being aimless.

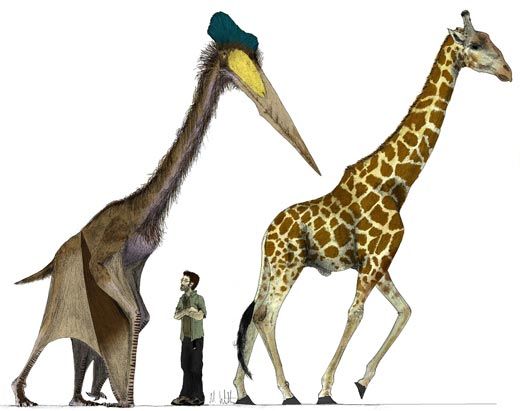

Why Pterosaurs are not like Sea Gulls

How did a giant pterosaur called an azhdarchid capture prey? Not while flying, according to a University of Portsmouth, England, analysis of fossils and tracks. Azhdarchid's padded feet, short wings and stiff neck indicate it didn't feed aloft as today's seabirds do. It may have walked, balanced on bent wings, to pursue small animals (not including the bearded guy at left, who's just for scale).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)