Wiseguys with Wings

“Mafia” cowbirds muscle warblers into raising their young

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cowbird_male.jpg)

Some cowbirds make warblers an offer they can't refuse: Brood over my eggs, or I'll rough up your nest.

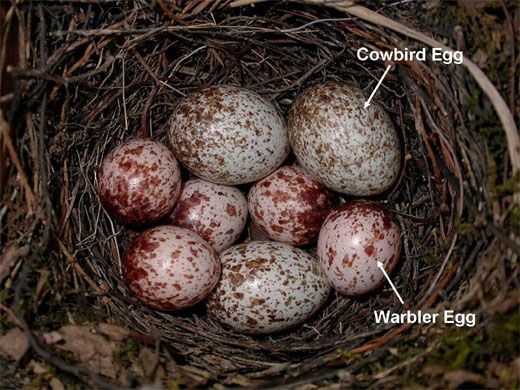

Cowbirds are a parasitic species that lay eggs in the nests of other birds, called hosts, which accept these eggs and nurse them as their own. Scientists have debated this acceptance; many believe the hosts have not coexisted with parasitic birds for long enough to evolve defenses. Others have suggested that the hosts either can't recognize foreign eggs or are too small to remove them.

New research gives evidence for another explanation: The cowbirds engage in "mafia behavior." The parasitic birds lay their eggs in host nests when the tending female is away, often under the cover of darkness. The cowbirds then monitor these nests and destroy them if the host removes the foreign eggs.

"We found that female cowbirds do in fact return and damage the eggs and [host] nests when we remove their eggs," says avian ecologist Jeff Hoover of the Illinois Natural History Survey. "That type of behavioral can promote the persistence of acceptance in the host."

To study cowbird-host interactions, Hoover and his colleague Scott Robinson of the University of Florida manipulated nearly 200 warbler nests. In some nests, the researchers removed newly laid cowbird eggs; in others, the eggs were left alone.

Fifty-six percent of warbler nests in which parasitic eggs had been removed were destroyed, compared with only 6 percent of "accepting" nests, Hoover and Robinson report in an upcoming Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The cowbirds also ravaged warbler nests that were too far along in the brooding process to accept new eggs. In this scenario, called "farming," the cowbirds destroyed the nest, forcing the host to build a new one and lay a fresh set of eggs.

"The presence of these behaviors, the mafia and the farming, suggest that cowbirds are more highly evolved than we previously thought in terms of the tactics they might use as part of their reproductive strategy," says Hoover.

Cowbird reproduction relies entirely on laying eggs with hosts; in fact, says Hoover, they likely can't nurse their own eggs at all. Free from the burden of brooding, cowbirds can devote more energy to looting and monitoring nests, he says. The strategy works in the long-run, because hosts that accept the parasitic eggs produce more of their own young than do hosts that reject the cowbird eggs and have their nests destroyed.

In their study, Hoover and Robinson fingered cowbirds along as the culprit by making the nests "predator proof"—inaccessible to raccoons, snakes and other potential invaders.

But evolutionary biologist Stephen Rothstein of the University of California, Santa Barbara remains unconvinced. Video studies have shown that other birds not typically considered predators will destroy a host nest, he says. In addition, the only previous evidence of mafia behavior in birds was documented in a species of cuckoos, and the validity of that research remains debated.

The greater fear, says Robinson, is that excitement over mafia cowbirds will divert attention from the larger problems that impact bird species—namely, habitat loss. Hoover agrees.

"If we give people the idea that cowbirds are an equally important problem [as habitat loss]," says Rothstein, "we could have counter-productive effects on conservation efforts."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)