At a steady trot, wolves can go 20 miles without breaking stride and cover 50 miles in a day. Their long thin legs move with the inevitability of bicycle wheels, with the rear foot landing in the exact spot just vacated by the front foot and the rest of the wolf flowing along. They travel with a look of intense purpose—ears pricked up, eyes keen, nostrils sifting the air for information—yet their movement over the land appears effortless.

The female gray wolf that biologists would call LAS01F was born somewhere in the Northern Rockies in 2014, possibly in Wyoming. In her second year of life, coursing with hormones, she left her natal pack to find a mate and a territory of her own, and kept going for another 800 miles or more.

She either crossed the Great Basin Desert in Utah and Nevada, or she made a much longer journey through Idaho and Oregon. Whichever passage she took, she was hunting by herself for the first time in unfamiliar terrain, learning to find water, cross roads, stay hidden from human beings.

At regular intervals she would have scent-marked her trail so other wolves, and preferably an unattached male, might find her. She would have howled often, listened carefully, and if she journeyed across the Great Basin—heard nothing in response. As far as we know, there were no other wolves in that vast stretch of ground.

It’s difficult to say why this particular female made such an epic journey. A small minority of wolves are long-distance travelers, and no one really knows why. It’s probably best understood as a personality trait; there is some evidence that the behavior may run in families.

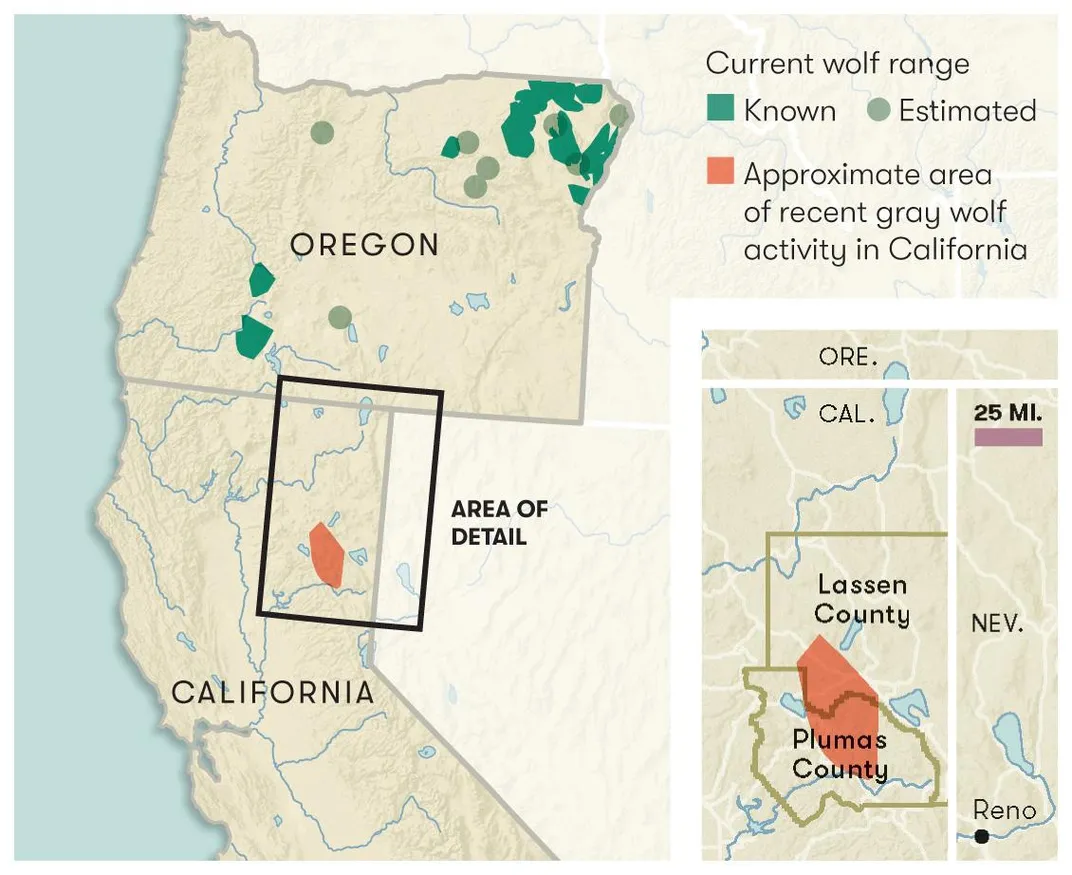

After traveling for at least a month, and perhaps longer, she reached the forested mountains of northeast California. There was clean water in the streams, blacktail and mule deer to hunt, a few elk, not too many humans, and features in the landscape that gray wolves find appealing: high plateaus, forested ridges, meadows. There were also thousands of cattle and sheep. We might say she was recolonizing ancestral ground, for it was here in Lassen County that the last wild wolf in California was shot and killed, in 1924, as part of the centuries-long extermination campaign that nearly wiped out wolves in the lower 48.

In late 2015, soon after her arrival in Lassen County, she entered human knowledge systems for the first time. A trail camera captured a blurry image of a “lone wolf-like canid,” as the California Department of Fish and Wildlife described it. In February 2016, the same canid, weighing approximately 75 pounds with a distinctive bent tail, was confirmed as a gray wolf and given a name, LAS01F, designating the first female wolf in Lassen County in nearly a century.

Soon afterward a young male wolf dispersed from a pack in southern Oregon and showed up in Lassen County, having traveled at least 200 miles. Through howling or scent-marking or both, the two young wolves found each other and liked each other, which is by no means a foregone conclusion. Wolves come in a wide range of individual personality types. Some breeding-age males and females, regardless of the mating drive, simply don’t get along.

The following spring, in 2017, LAS01F dug herself a den on a recently logged mountain slope, and birthed her first litter of pups. In 2020, she produced her fourth litter and expanded her family to at least 15. The Lassen pack, as it’s known, is the only wolf pack in California.

For environmentalists in the Golden State, the return of the wolf is a cause for celebration. Amaroq Weiss, a wolf advocate for the Center for Biological Diversity, says, “We, as Euro-Americans, hated wolves so much that we tried to wipe them off the earth. Now we have a very rare second chance to allow these beautiful, highly intelligent, ecologically essential animals to return. We still have the habitat for them in California, and the wolves are finding it. All we have to do is let them enter, and then let them live.”

In Lassen County, however, ranching is a mainstay of the local economy and anti-wolf sentiment runs high. Rumors and wild theories abound; some people say the wolves were deliberately introduced by the state of California, the federal government or shadowy environmentalists. Others accept the evidence that wolves are making their own way into California, but see no reason such notorious predators should be allowed to stay.

Many cattle and sheep ranchers are foretelling economic ruin. Most hunters are convinced that wolves will reduce the already dwindling deer population to insignificance, and some local residents are concerned for their safety. Such views are no longer just a matter of personal opinion. In some quarters, they are official policy. In April 2020, the Lassen County Board of Supervisors issued a statement describing wolves as an “introduced, invasive and noxious pest.”

* * *

One June day in 2017 Kent Laudon, a wildlife biologist, caught LAS01F in a leg trap. He approached her with a tranquilizer stick, and felt the softness of her fur as he attached a radio collar. Laudon, 57, originally from Wisconsin, has studied wolves for 24 years, working in Montana, Idaho, Arizona and New Mexico. Trapping and collaring is a vital part of his job, but he has never learned to enjoy it. “People think that a wolf in a trap would be snarling and vicious, but they’re so afraid of people that they look pitiful, like the boogeyman is coming to get them,” he tells me, as we talk at a campfire in the mountains. “Trapping is hard on them, but they do get over it, and what we learn from the collars is so valuable. It’s very hard to build a conservation plan without collared wolves.”

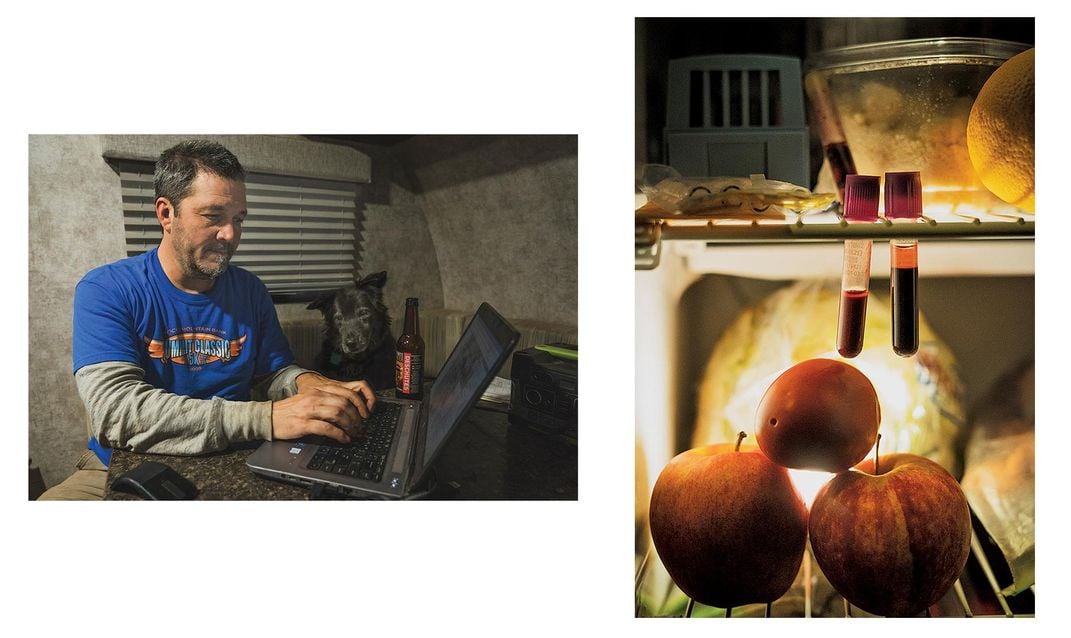

Laudon has been camped for weeks in a small trailer at a remote location inside the Lassen pack’s 500-square-mile territory. Working 14- and 15-hour days in the field, subsisting on jumbo cans of Dinty Moore beef stew, he shares the trailer with his scruffy 16-year-old dog Sammie. Laudon is wearing a Mohawk hairstyle to support a friend undergoing chemotherapy, and he has cut Sammie’s hair in a similar style.

Laudon is employed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to conserve and manage the state’s gray wolf population—the Lassen pack and occasional dispersers from Oregon—and the job requires two different skill sets. One is field biology: trapping, radio-collaring, mapping data points, monitoring trail cameras, making field observations and pup counts, identifying den sites, collecting scat samples for the DNA lab in Sacramento, investigating livestock depredations. The other part of the job, which he considers more important, is building personal relationships with ranchers and local communities.

“It’s all social psychology and we get zero training in it, but people are really the key to long-lasting conservation,” he says, talking fast and gunning his truck along a dirt road in the forest. “It’s a real shock for people when wolves show up out of the blue, and there will inevitably be some livestock depredations, even though, 99 times out of a hundred, wolves will walk right past cattle and sheep without doing anything. I’m here to help people understand that living with wolves is not as bad as they think. But first I have to gain their trust. And that means breaking down a lot of barriers.”

We drive past a group of cattle moving through the pines. He stresses that he isn’t against ranching. For one thing, the great tracts set aside for grazing can benefit wolves by limiting habitat loss. “If livestock producers start going out of business because of wolves, then the habitat is at risk from developers, and nothing is worse for wolves than condos, holiday homes and busy highways.” He goes on, “Obviously I think wolves are neat critters and that’s why I’m a wolf biologist, but I totally understand why they’re worried about their livelihood, stressed out, and suspicious of a guy like me in a government uniform telling them it’s not that bad.”

He drives out of the trees into a broad, wildflower-strewn alpine meadow. In the middle of it, festooned with ravens and vultures, lies a dead cow that was reported to Laudon by a ranch hand as a possible wolf kill. Laudon parks the truck and the birds flap away as we approach on foot. Next to the carcass, freshly imprinted in mud, is the unmistakable paw print of a wolf. It’s the same shape as a dog track but much larger and freighted with centuries of sinister folklore.

“A lot of people would see this and jump to the wrong conclusion,” says Laudon after carefully inspecting the carcass. “This wasn’t a wolf depredation. There’s no predator wound. This cow got sick and died and then the wolves came in and scavenged it. They’re big-time scavengers with an amazing ability to find stuff.” He thinks wolves study the flight patterns of vultures and other birds in order to locate carrion.

In the five years since LAS01F established her pack, the state fish and wildlife department has carried out more than 50 investigations into possible wolf depredations in Lassen and Plumas counties. In 2015 and 2016, investigators found no confirmed wolf kills. In 2017, there was one confirmed kill. The following year saw five confirmed kills, plus one probable and four possible. In 2019, there were another five confirmed kills, plus one probable and one possible. In 2020, the pack killed eight head of livestock. To put those numbers in perspective, there are an estimated 38,630 cattle and calves in Lassen County, and hundreds die every year from disease, birthing problems and harsh weather.

“The fact that losses to wolves are usually low doesn’t make most producers feel any better about it,” says Laudon. “It’s another headache in a business that has big capital outlays, unwanted regulations, a fickle market and slim profit margins. Now they’re forced to deal with wolves as well, and they have no voice, no vote, no control. And they’re supposed to just stand there and watch if wolves are killing and eating their stock, because it’s against the law to shoot a wolf in California.”

In Montana, ranchers have the right to shoot wolves to protect livestock, state game officers kill depredating wolves, and there’s a hunting and trapping season that took out nearly 300 wolves in 2019. In most of Wyoming, it’s legal to shoot wolves on sight as vermin, or chase a wolf with a snowmobile until it collapses from exhaustion and then run over it until it’s dead; a bill outlawing this practice was resoundingly defeated in the state legislature in 2019. In Idaho, year-round hunting of wolves is permitted in most of the state, and it’s legal to trap wolf pups outside a den and beat them to death.

In California, however, wolves are protected as an endangered species, a state law that was enacted largely in response to a celebrity wolf known as OR-7, or Journey.

* * *

Nearly all the wolves in the Northern Rockies and Pacific Northwest are descended from 66 Canadian gray wolves that the federal government introduced to Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho in 1995 and 1996. (The others descend from Canadian gray wolves migrating south across the border.) Despite bitter opposition from ranchers, hunters, local communities and state politicians, wolf populations increased rapidly in Yellowstone and Idaho, the animals resumed their ancestral position as apex predators and their yearlings began to disperse.

The first wolves reached Washington State in the late 1990s, and there was a resident pack by 2008. The following year, two Idaho wolves, one outfitted with a radio collar, swam across the Snake River and established Oregon’s first pack in the far northeast of the state. In 2011, a young male from their second litter was radio-collared and named OR-7—the seventh wolf collared in Oregon.

In September 2011 he traveled southwest into parts of Oregon that hadn’t heard wolves howling since 1947. The lovelorn wolf, as he was often characterized—although not by ranchers—became a media celebrity. The Oregonian newspaper featured him regularly in a cartoon strip and sold “OR-7 for President” bumper stickers. A Twitter account set up in the wolf’s name listed his hobbies as “wandering, ungulates,” and asked “Why is everyone so worried about my love life?” Oregon Wild, a conservation group, launched a contest to give the wolf a more inspiring name and “make him too famous to kill.” Out of 250 submissions, including one from Finland, the winning name was Journey.

On December 28, 2011, Journey crossed the California state line into Siskiyou County. While the Lassen female is the most successful and long-lived wolf to enter California, OR-7 was the first, and thanks to his radio collar, the public was able to follow his travels. He made headlines in state and national newspapers, appeared on more than 300 websites around the world, and inspired two films and two books. He wandered through Siskiyou, Shasta and Lassen counties before returning to Oregon in March 2012. Then he went back to northern California for nearly a year. In 2013, at the ripe old age of 5, having traveled more than 4,000 miles, he finally found a mate in southern Oregon and established the Rogue Pack.

During OR-7’s first foray into California, conservation groups petitioned the Fish and Game Commission to list the gray wolf as a protected species under the California Endangered Species Act. Even though OR-7 was the only wolf in the state, they argued, others were bound to follow and would need protection.

There were dozens of public hearings, well attended by wolf supporters as well as opponents from the livestock industry. At the final hearing in Fortuna, in June 2014, a crowd of 250 packed a room. Some were dressed in wolf suits. All of them had heard, just a few hours previously, that wolf pups had been photographed for the first time in southern Oregon and OR-7 was almost certainly their father. Some of these pups were expected to disperse into California. The testimonies from wolf supporters were impassioned, sometimes tearful, and included an a capella song.

To the shock and surprise of the California Cattlemen’s Association and other wolf opponents, the commission voted 3 to 1 to override the recommendation of its own staff and approve the listing. “No land animal is more iconic in the American West than the gray wolf,” said Michael Sutton, then president of the commission. “Wolves deserve our protection as they begin to disperse from Oregon to their historic range in California.” Amaroq Weiss, from the Center for Biological Diversity, says, “California is the most liberal, progressive state that wolves have returned to, and we really rolled out the welcome mat for them.”

Some of OR-7’s offspring did indeed go south into California; it was one of his sons who mated with LAS01F and established the Lassen pack. Then there was the short-lived Shasta pack. In 2015, two Oregon wolves raised a litter of five pups in Siskiyou County, California, killed a calf and then disappeared. Weiss and other wolf activists suspect they were killed by the “3-S” method, as it’s known in the rural West: “Shoot, shovel and shut up.”

Perhaps the most extraordinary odyssey was made by one of OR-7’s daughters, a radio-collared yearling named OR-54. She left the pack in southern Oregon in January 2018, dispersed into California, roamed through eight counties, killed a few cattle, crossed Interstate 80 to briefly visit Nevada, crossed back again and returned twice to Oregon. In all she traveled more than 8,700 miles looking for a mate, or a pack to join, but she was unsuccessful and died under suspicious circumstances in Shasta County, California.

State wildlife officials are investigating her death as a possible crime under the Endangered Species Act, along with that of a young male wolf, OR-59, that was found shot by the side of a road in Modoc County. Killing a wolf in California carries serious penalties, including a $100,000 fine and probable imprisonment, but the disappearance of the Shasta pack and the deaths of OR-54, OR-59 and a yearling female from the Lassen pack suggest that the deterrent doesn’t work on everyone. There has been no successful prosecution to date.

“It’s tough for wolves out there, even when they have legal protection,” says Kent Laudon. “Their average life span is four or five years, and we are their main cause of death. They get shot, hit by vehicles, occasionally hit by trains, occasionally poisoned. It’s very rare for a wolf to die of old age, although I’ve known a few who’ve made it to 12 and 13.”

* * *

On a bright cool afternoon in the mountains of Lassen County, I visited Wallace Roney. He’s a stout white-haired man with leathery hands and a stern, unyielding manner that belies a lively sense of humor. His family has been raising cattle in California since the 1850s and his forefathers helped eradicate the wolf from the state. His land-and-cattle company owns four ranches in central and northern California, leases an additional 100,000 acres of public and private grazing land, and runs a cow-calf operation with 500 to 600 head. He uses this Lassen County ranch primarily as summer forage.

Roney believes strongly that ethnicity, or “blood,” is the main driver of human behavior, and he’s proud of his own Scottish lineage. “We’re a fighting people,” he says. “We don’t walk away from adversity. But if this carries on, I’ll have no choice but to give up and get my cattle out of here. We can’t afford to feed the wolves.”

The first confirmed wolf depredation in California in more than a century happened on Roney’s land; the Lassen pack took down a 600-pound heifer in October 2017. Since then, he claims to have lost “at least half a dozen” animals to the wolves, which he says didn’t meet the investigators’ protocols for confirmed kills. He’s certain the pack has killed many more of his cattle and calves in remote areas.

For him it’s primarily about money, but for his wife, Billie, he says, it’s more emotional, “It’s tough for anyone to watch wolves eat your calf, or your dog, and not want to protect that animal. But they took that right away from us. If we protect our animals with guns, we become criminals.”

Standing next to Roney, nodding along solemnly, is his tall, slim, college-going grandson George Edward Knox III. He has been protesting the wolves by posting photographs of half-eaten calves to his Instagram account.

Behind them stretches a lush meadow, 6,000 feet above sea level, where a group of heifers is standing inside an unusual enclosure. It is formed by long lines of rope, tethered to fence posts and hung with strips of red fabric that dance and flap in the breeze. Known as fladry, this form of enclosure has been used for centuries in Europe to deter wolves, who seem to be frightened of the moving fabric.

The fladry was installed here, at no cost to Roney, by USDA Wildlife Services, a federal agency dedicated to resolving wildlife conflicts, in partnership with the state wildlife agency. Roney acknowledges the fladry is effective—there have been no wolf kills inside it—but he says it has drawbacks. The cattle have to be lured into the enclosure at night with salt and molasses, which is time-consuming. They soon graze down all the grass inside the fladry, degrading the land and failing to put on weight, and the fladry itself requires upkeep and repairs. Before the wolves, the cattle could graze anywhere they pleased. “Life was easier and more profitable,” says Roney.

He leases grazing allotments in the nearby national forest and on private timber company land, and typically turns his cattle loose without supervision. The weight they gain on the allotments translates into profit. “Since the wolves have been here, our weight gain is down because the animals are getting chased and harassed and they’re stressed,” he says. “This year we’re not even using our allotments. With the death loss and the weight loss, it’s not worth it. That’s 60,000 acres we’re not grazing.”

Roney rejects the idea that the wolves found their own way to Lassen County. “Do I look that stupid?” he says. He claims that he found the cage that the wolves were transported in before their release. “It was 35 miles from here at a camp in the woods,” he says. “They left garbage laying around and a bag of dog food.” Asked who “they” might be, he says, “I won’t speculate.” He claims the government removed the cage because it was damning evidence of the illegal plot to introduce wolves to California. One can hear many variations on this theme from ranchers, and not just in Lassen and Plumas counties.

California officials are unequivocal, though, in disputing such conspiracy theories: “The California Department of Fish and Wildlife has not reintroduced gray wolves in the state.”

Forty miles south of Roney’s ranch in the county seat of Susanville, a town of 16,000 on the Susan River, I sat down with cattle rancher and county administrative officer Richard Egan. He does not hold with the view that wolves were smuggled into Lassen County, but he still regards them as an introduced and alien species. “The state has presented no evidence that the gray wolf, which the government introduced into this country from Canada, was the native subspecies of California,” he says, sitting across a conference table in the county building. “Nor did the state evaluate the damage to wildlife and other interests that this invasive vermin was likely to cause.”

For these reasons, Egan and the Board of Supervisors have called on the fish and game commission to delist the gray wolf from the California endangered species act, but he acknowledges it’s not likely to happen. “The commissioners are the political appointees of an extremely liberal state,” he says. “The liberals in the cities want wolves. The people of Lassen County do not want wolves, because we actually have to deal with them, but there’s only 20,000 of us in a state with 40 million people.”

Like Wallace Roney, Egan thinks the wolves are killing many more livestock than the official investigations show: “If you find one killed, there’s seven you don’t find.” He praises Laudon for cooperating with livestock producers, letting them know where the wolves are and helping them with nonlethal deterrent methods, but it’s not enough. “There has got to be a state-funded compensation program,” he says. “The people of California are taking away my right to protect my property, my livestock, so they need to compensate me for the value of my livestock killed by wolves.”

In November 2020, the Lassen County Board of Supervisors approved a resolution calling for state compensation when pets, livestock or working animals are killed by wolves, mountain lions or bears. This was purely a political strategy, since there is no funding to back up the resolution. They’re hoping it leads to a discussion about compensation in the state legislature, and then a bill that can pass. There are compensation programs in all the other states where wolves have returned. Ranchers are reimbursed for the full market value of the lost animal, as determined by its age, weight and breeding, if a wolf kill is confirmed by investigators. While ranchers grumble that many wolf kills are overlooked, and wolf supporters accuse ranchers of making spurious or exaggerated claims, the payouts do lessen the financial hardship of wolf depredations, if not the anger and frustration. Initially, environmentalists had hoped compensation programs would help ranchers become more tolerant of wolves, but that hasn’t happened. There has been no decrease in wolf poaching or in requests for the lethal removal of wolves in states that offer it, and anti-wolf rhetoric remains as vehement as ever.

* * *

The sun is setting, cattle are grazing placidly in the golden light, and the wolves are in the timber on the ridge across the meadow. Concealed behind brush and trees, we wait for a repeat of yesterday’s performance, when eight pups came out at sunset to romp and frolic in the meadow. Some were gray and some were black. The Lassen pack has a new alpha male, a black wolf of mysterious origins. State wildlife officials have a forensics lab in Sacramento, where genetics researcher Erin Meredith extracts wolf DNA from scat and hair samples supplied mainly by Kent Laudon. She then searches her database, which has the genetic markers of about 450 wolves, compiled in collaboration with her counterpart researchers in other states, looking for relatives and piecing together family trees. (This kind of data is what tells researchers that LAS01F hails from the Northern Rockies.) Meredith has the black wolf’s DNA, but she hasn’t found any relatives.

Laudon doesn’t know what happened to the old alpha male, OR-7’s son, or if he’s still alive. More than anything, the arrival of the new male has increased his respect for the alpha female. “OR-54 traveled 8,700 miles all over northern California trying to find a male and she came up with nothing,” he says. “This Lassen female has bred with two and had a litter every year.” He’s almost certain the new male has fathered two litters this year, one with the alpha female and another with one of her sexually mature daughters. That explains why 15 pups have been counted in the pack this year. He suspects there might be more.

When a wolf pup is 8 to 10 weeks old and weaned, its mother moves it from the den to the rendezvous site, a place where pack members gather to sleep, play, eat and socialize before the night’s hunt. This year the rendezvous site is on the forested ridge above the meadow. “Right now the adults are probably waking up and lounging around, and the pups are probably clambering all over them,” he says. “Let’s see if they come out again.”

We watch the meadow and the ridge and listen closely but nothing happens except the sinking of the sun and the advance of shadows. Then, in the twilight, an adult wolf lets out a long, mournful howl that seems to hang in the air for several moments until the rest of the pack joins in. We hear the extraordinary harmonics that emerge as the wolves shift and blend their frequencies, and then it all turns to yipping, yelping, yiping chaos as the pups try to join in.

For 18,000 years, the survival of wolves in North America depended on prey animals, water and resistance to disease. Now it depends on fundraising, advocacy campaigns, media coverage, political support, legal protection and enforcement. In California, where the environmental movement is strong, the future appears fairly bright for wolves. The yipping pups on the ridge have a decent chance of finding mates and raising their own pups in a few years.

One of their older siblings has moved into Oregon, and more Oregon wolves are, in turn, dispersing into California, including what appears to be a new breeding pair. Perhaps others will make the long journey from the Northern Rockies, as the Lassen female did. Colorado has voted to reintroduce gray wolves to the western slopes of the Rockies, and some of their offspring will surely disperse into Utah and Nevada.

“Once all these dispersers start finding each other, populations are going to jump and wolves will start showing up in a lot of new places,” says Laudon. “There’s so much good habitat out there, but ultimately it all comes down to people, what they can handle, how they feel, how they vote, the stories they tell.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/21/b4219a36-bbf6-4dca-b784-e42a78d5a7cd/mobile_-_opener_-_apr2021_b09_wolves_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/15/25154b34-37ab-4d06-9ff3-62457f6ec1b6/opener_-_apr2021_b09_wolves.jpg)